Reading an Archive of Everyday Life

- Amy Beth Stanley

In 2008, as a beginning assistant professor at Northwestern University planning my first survey course on the history of the Tokugawa era (1600–1868), I wanted to assign more readings on everyday life in villages. At the time, there were not many primary sources available in English, so I decided to translate some representative documents from the Niigata Prefectural Archives. On their website, I found the “Internet Document Reading Course,” a series of transcriptions and explanations of materials in their archive. It was there I first encountered the writing of a woman named Tsuneno, a daughter of a temple family from the tiny village of Ishigami in Kubiki County in Echigo Province. She had run away to the shogun’s capital of Edo in 1839, and in the letter that the archive had on display, she wrote to her mother to describe her new life as a maidservant in the theater district. “Everything in Edo is delicious,” she said.

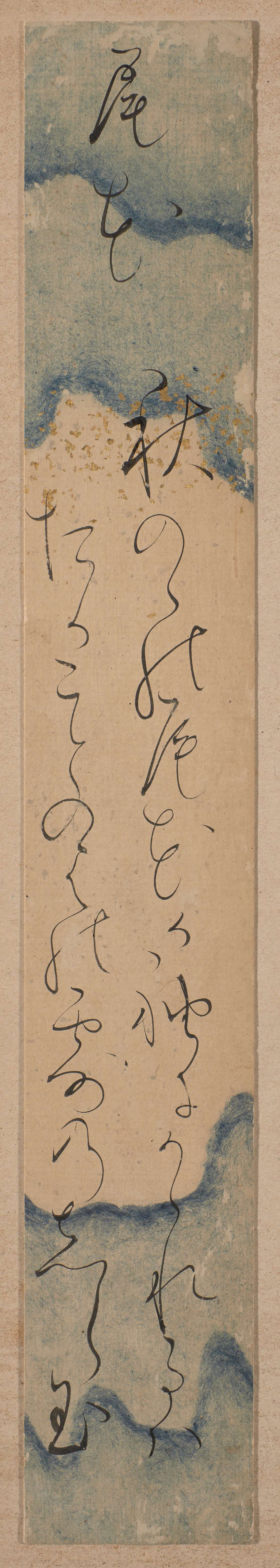

Tsuneno’s voice was so simple and direct that I could hear it in my head. But it sounded suspiciously modern and straightforward. Could this really be the writing of a nineteenth-century Japanese woman? In my previous reading in Tokugawa history, I had encountered the abject, awkward prose of a post-station prostitute; the elevated, poetic language of samurai women’s travel diaries; and the matter-of-fact, efficient lists in merchant wives’ household accounts. I was unprepared for Tsuneno’s style, not only how it looked on the page—dashed off, confident—but also its forcefulness.

I went to the archive in person and read Tsuneno’s other correspondence, which was preserved in her family’s papers (the Rinsenji monjo). I noticed that her favorite word seemed to be “I” (watakushi), and her letters often took the form of demands: “send me my clothes,” “go get the money I left with my uncle,” or “redeem my things from the pawnshop.” While she used traditional women’s forms, writing in kana and ending her letters with the respectful closing kashiku, she was never self-effacing. Her writing changed my ideas about how Tokugawa-era women thought about themselves. Never again would I believe that women were so enmeshed in the household system and so deeply embedded in their communities that they did not consider their individual desires. Tsuneno realized that her own ambitions and her family’s priorities were different, and though she often felt conflicted, she usually chose to pursue her own goals.

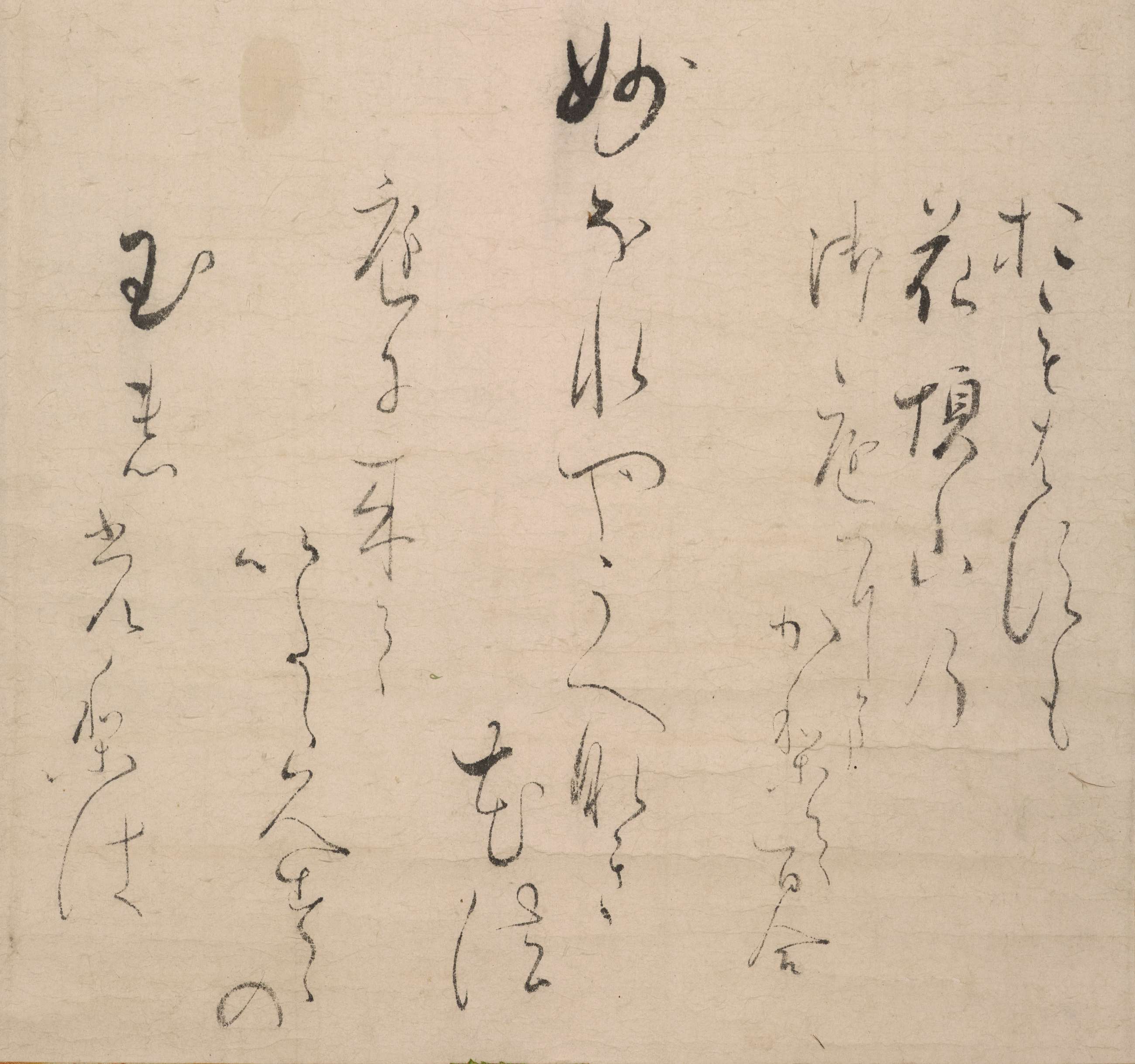

Tsuneno’s family’s archive contains over two thousand documents in a variety of hands. The men wrote in the epistolary style (sōrōbun), using complicated Chinese characters and occasionally referencing Buddhist doctrine. The family’s secretary wrote in the same style, and his drafts of outgoing correspondence survive, showing where he crossed out a phrase and reconsidered the wording. One correspondent, a man from the village doing seasonal work in Edo, wrote in a dark, blocky hand and employed a strange orthography, using characters in unexpected ways. Like Tsuneno, who rendered her own dialect in kana, he “spelled” phrases as they must have sounded to him. Meanwhile, Tsuneno’s aunt wrote in a graceful and feminine style, and her two sisters wrote in a hand that looks just like hers.

Through this remarkable archive, I encountered not only a variety of forms of writing but also a multitude of perspectives on everyday life. I could see, in these letters, lists, and diaries, how people of different genders and classes kept track of their daily business. I could follow a story of books lent, taxes owed, marriages planned, servants hired, children welcomed, and deaths mourned. Those dispatches from a vanished world were mundane and not always beautiful—there were blots and stains, miswritten characters, torn pages, and worm holes—but they were vital, immediate, and often astonishing.