Taking the Tonsure

Taking the tonsure is the ceremonial shaving of one’s hair to join a Buddhist monastic order. It was a symbolic act of leaving one’s past behind. In fact, becoming a nun literally translates to “leaving one’s home” (shukke 出家).

Tonsure did not mean, however, relinquishing one’s autonomy. On the contrary, it offered a form of liberation from societal expectations, such as the Three Obediences (of a woman to her father, husband, and son). It also enabled nuns to travel freely in times of state-imposed restrictions, which especially impacted women. Above all, it allowed them the freedom to pursue their art.

Women from all walks of life took the tonsure, from princesses (like Daitsū Bunchi) to entertainers (like Ōishi Junkyō). Still, this was an extremely difficult path to take and often entailed unimaginable determination.

Leaving their old names behind, taking new names as ordained nuns, these artists crafted new identities for themselves.

“Not coiffuring my hair

would leave my hands free

to spend my time at the desk.”

—Kaga no Chiyo

「髪を結ふ

手の隙明て

炬燵哉」

加賀千代

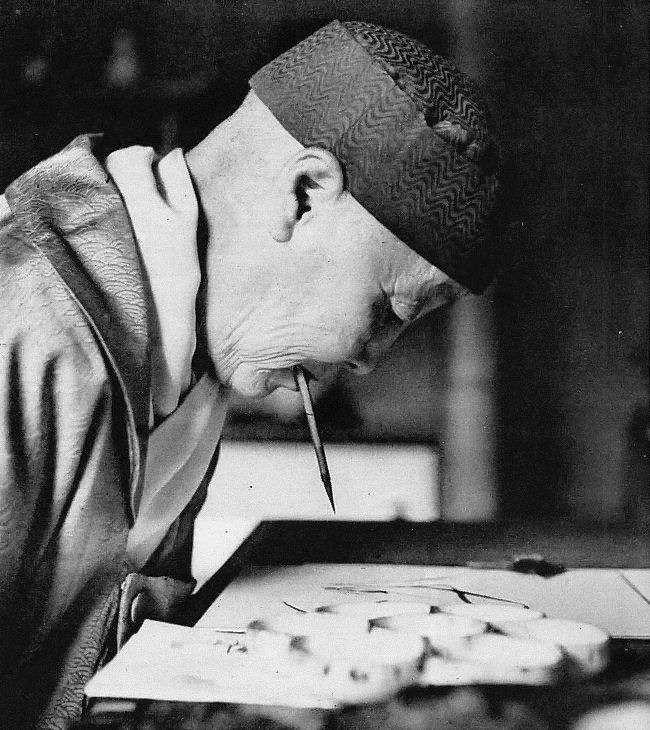

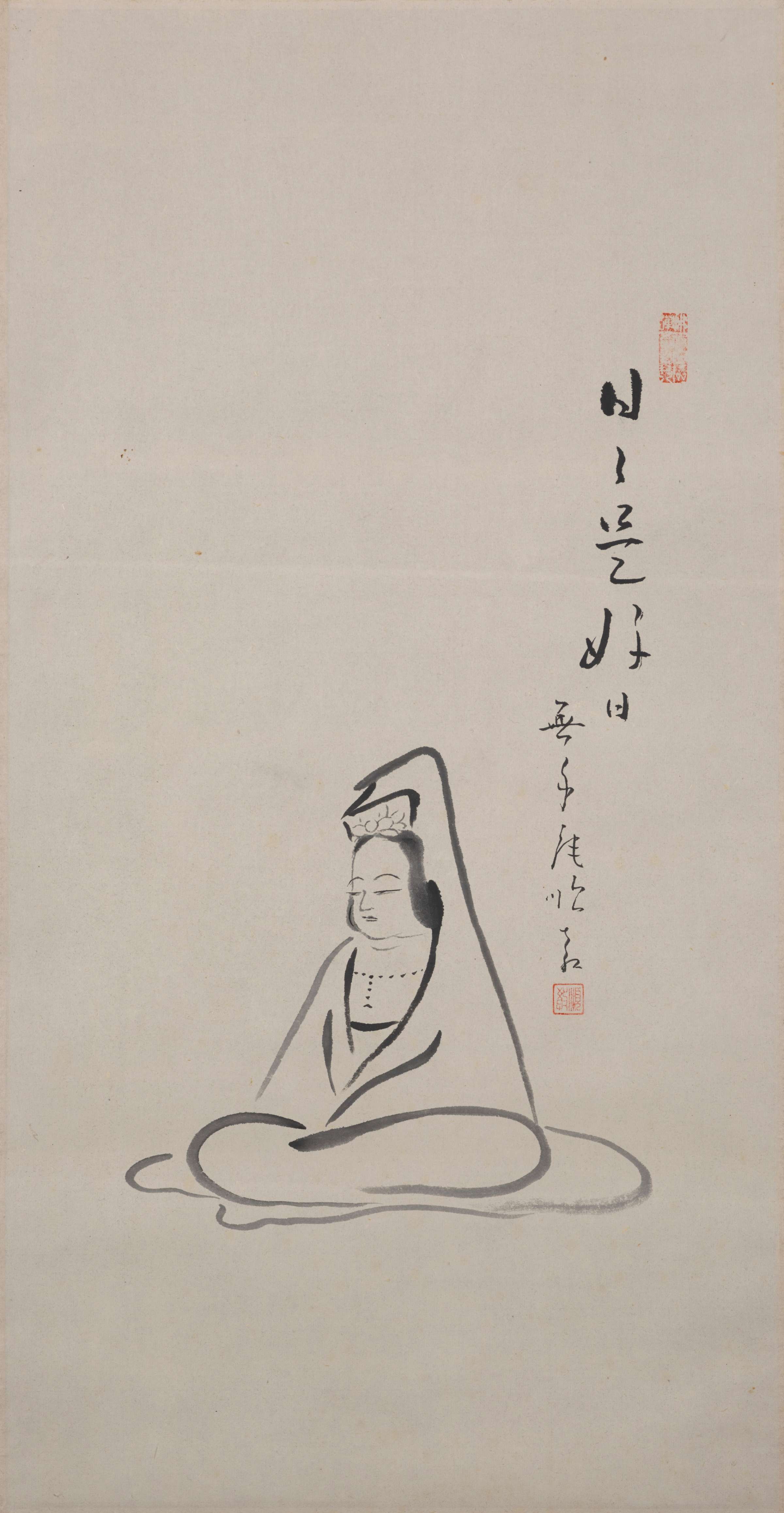

The nun-artist Ōtagaki Rengetsu is seen here brushing a poem onto her ceramics. Her elegant surroundings, more like a scholar’s study than a nun’s hut, alludes to her literati background and affiliation.

This is an imagined portrait done sixty years after Rengetsu’s death. Depicting her with feminine and manicured features, Suganuma Ōhō constructed quite a different portrait from the wizened likeness by her student, collaborator, and close friend Tessai.

“I took leave of this floating world. The day I thought I wished to see every famous nook and corner under the heavens and pay homage to every shrine and temple, I just took to the road, all by myself.”

—Tagami Kikusha

「浮世に暇あく身と成ぬれば、

天が下の名にあふくまぐま神社仏閣を拝詣せばやと思ひ立日を其儘に、

ひとり旅路におもむきぬ」

田上菊舎

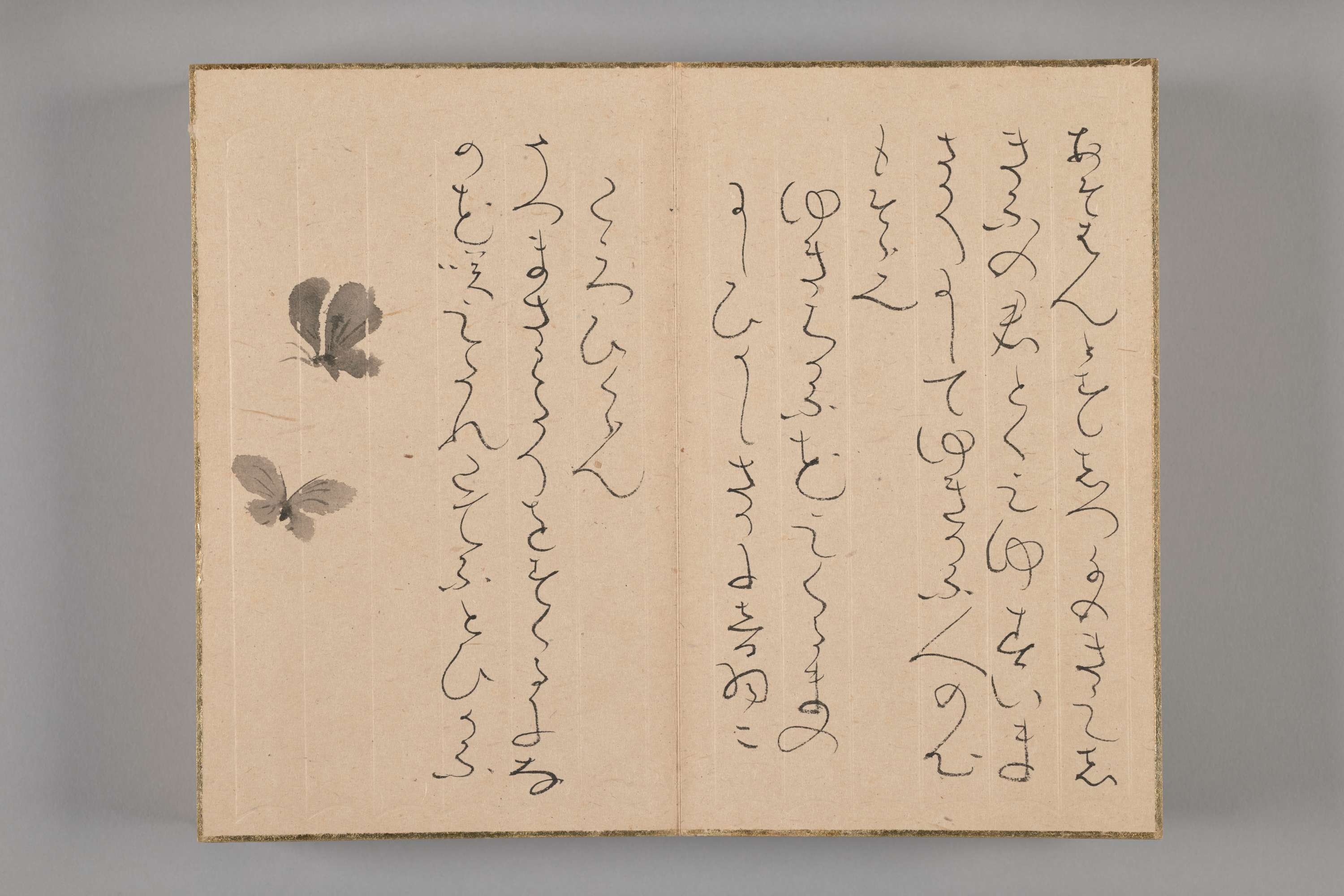

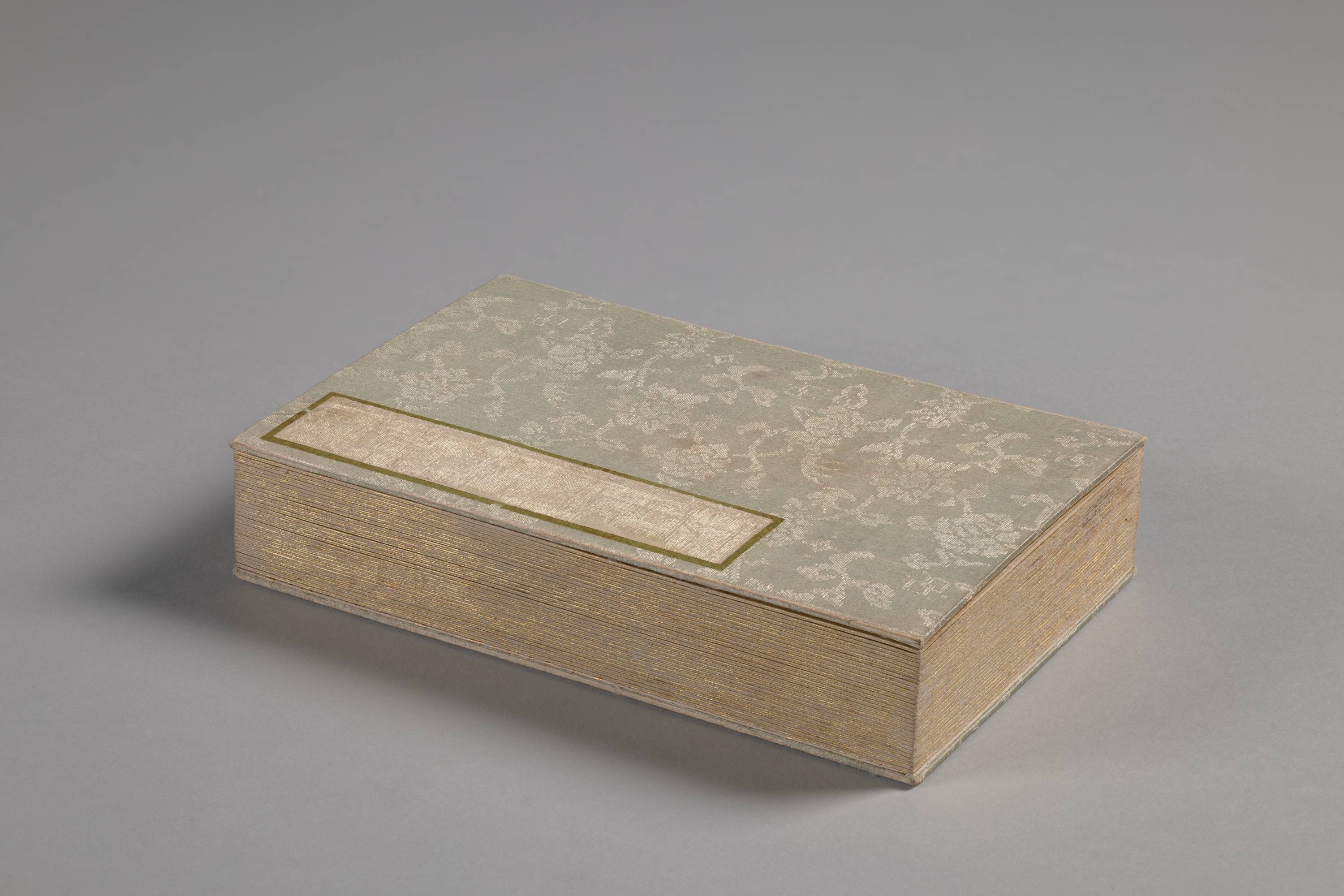

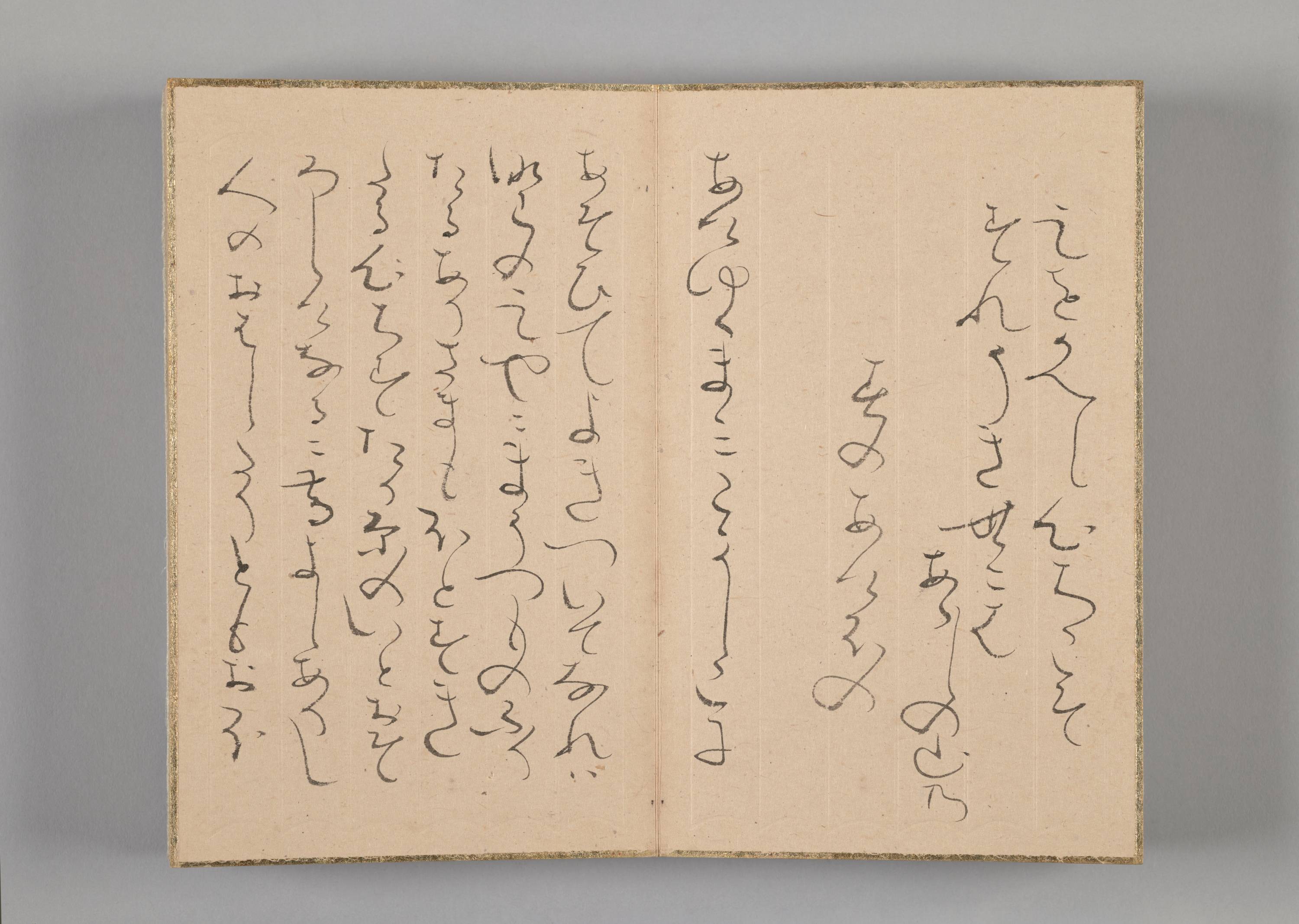

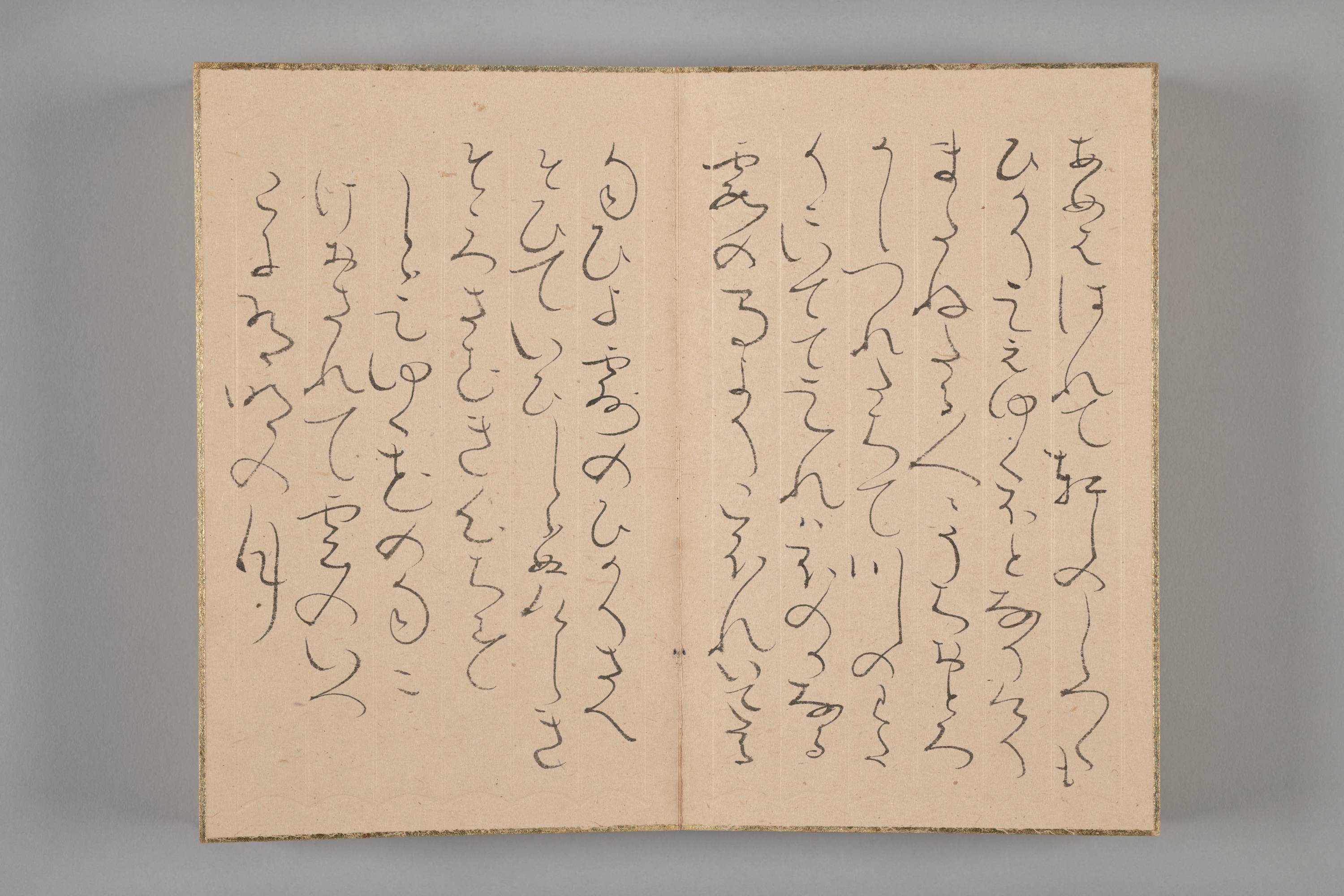

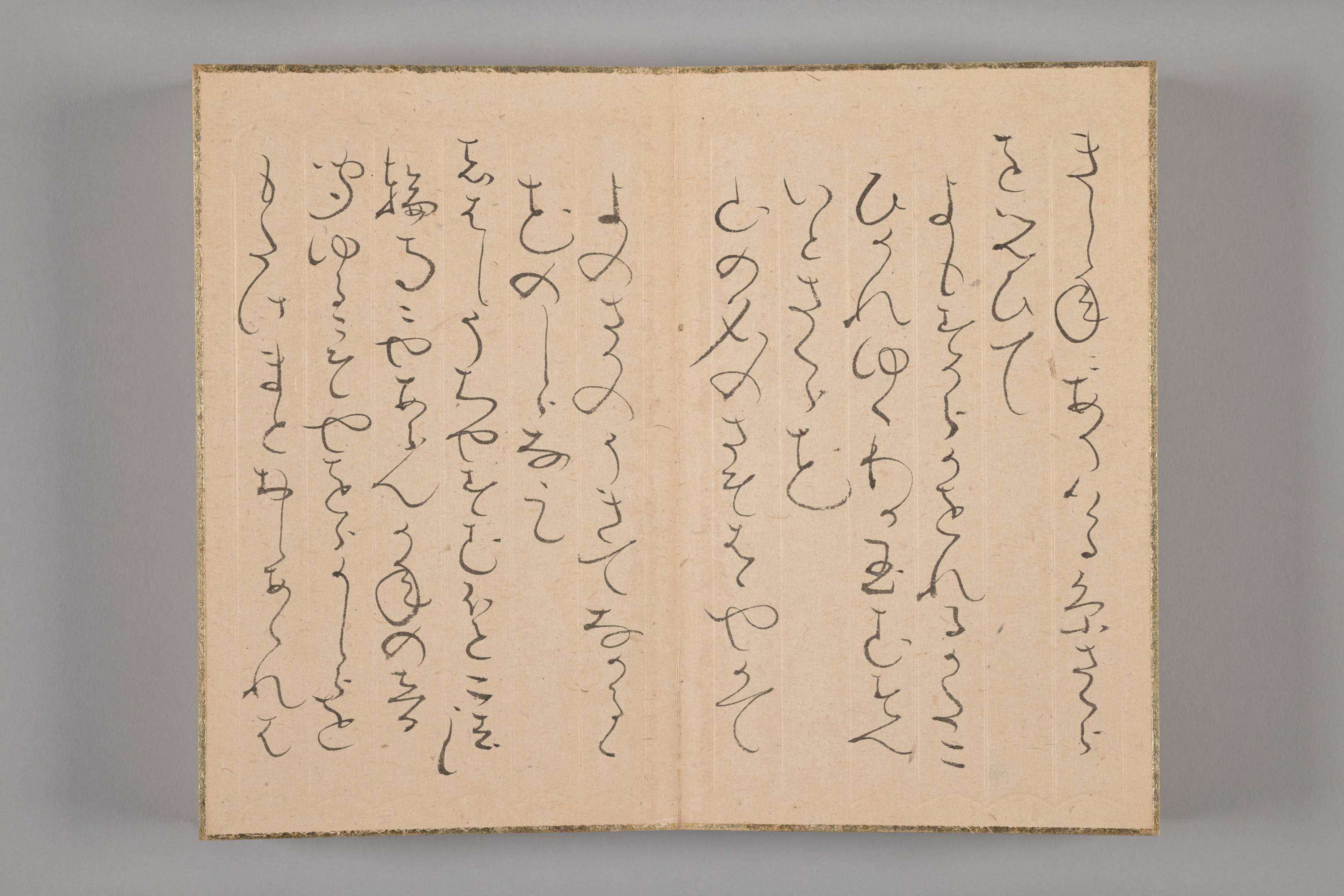

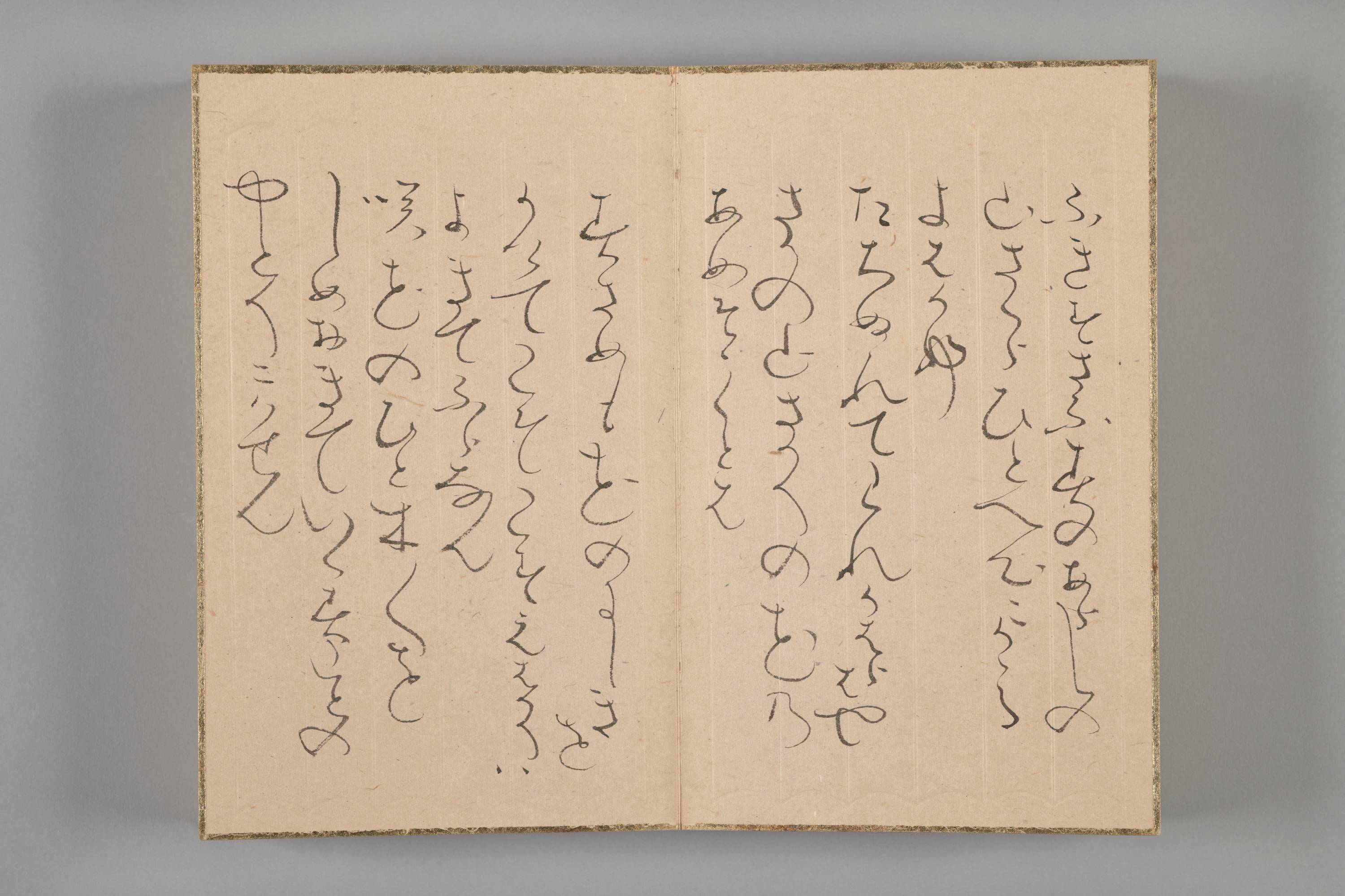

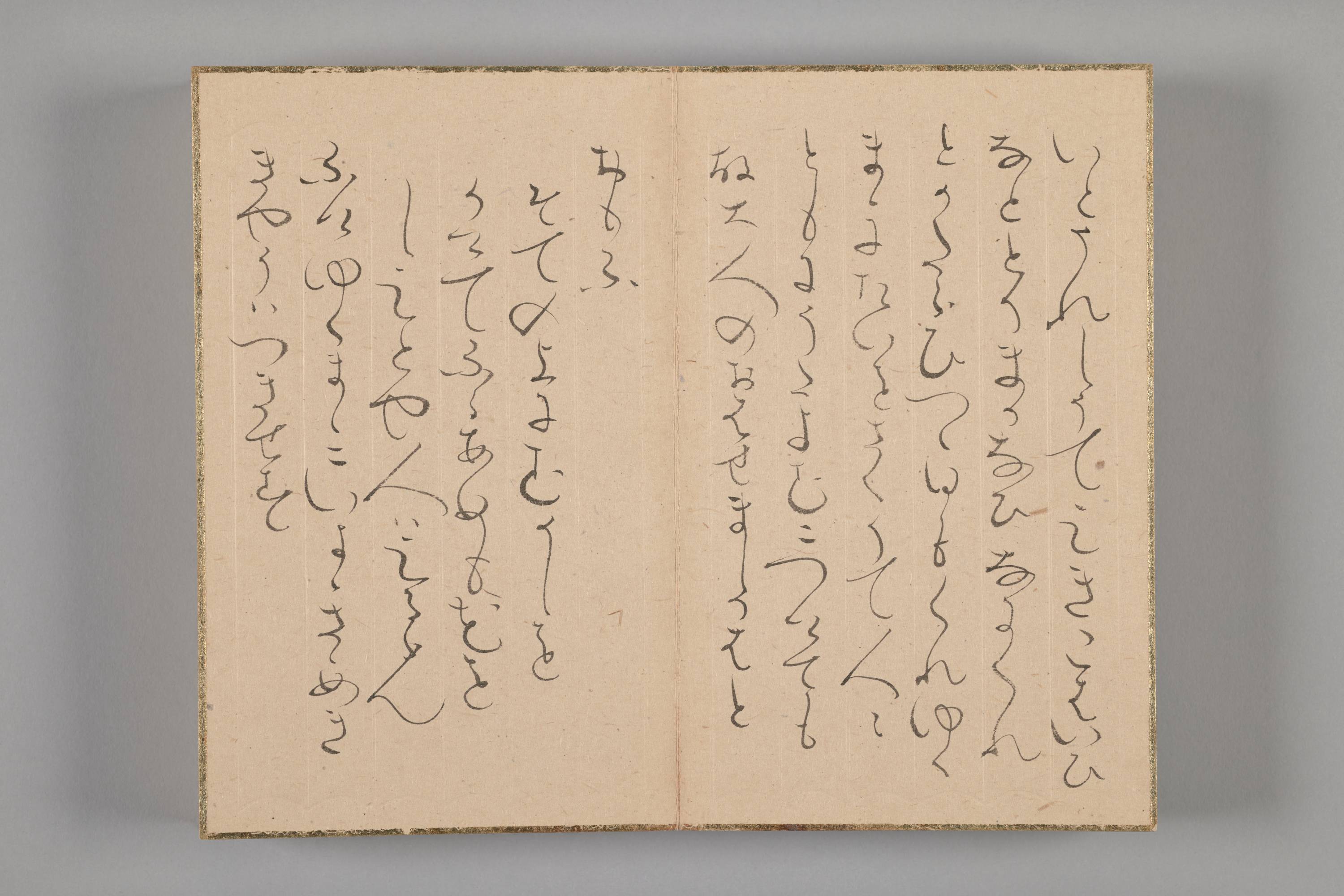

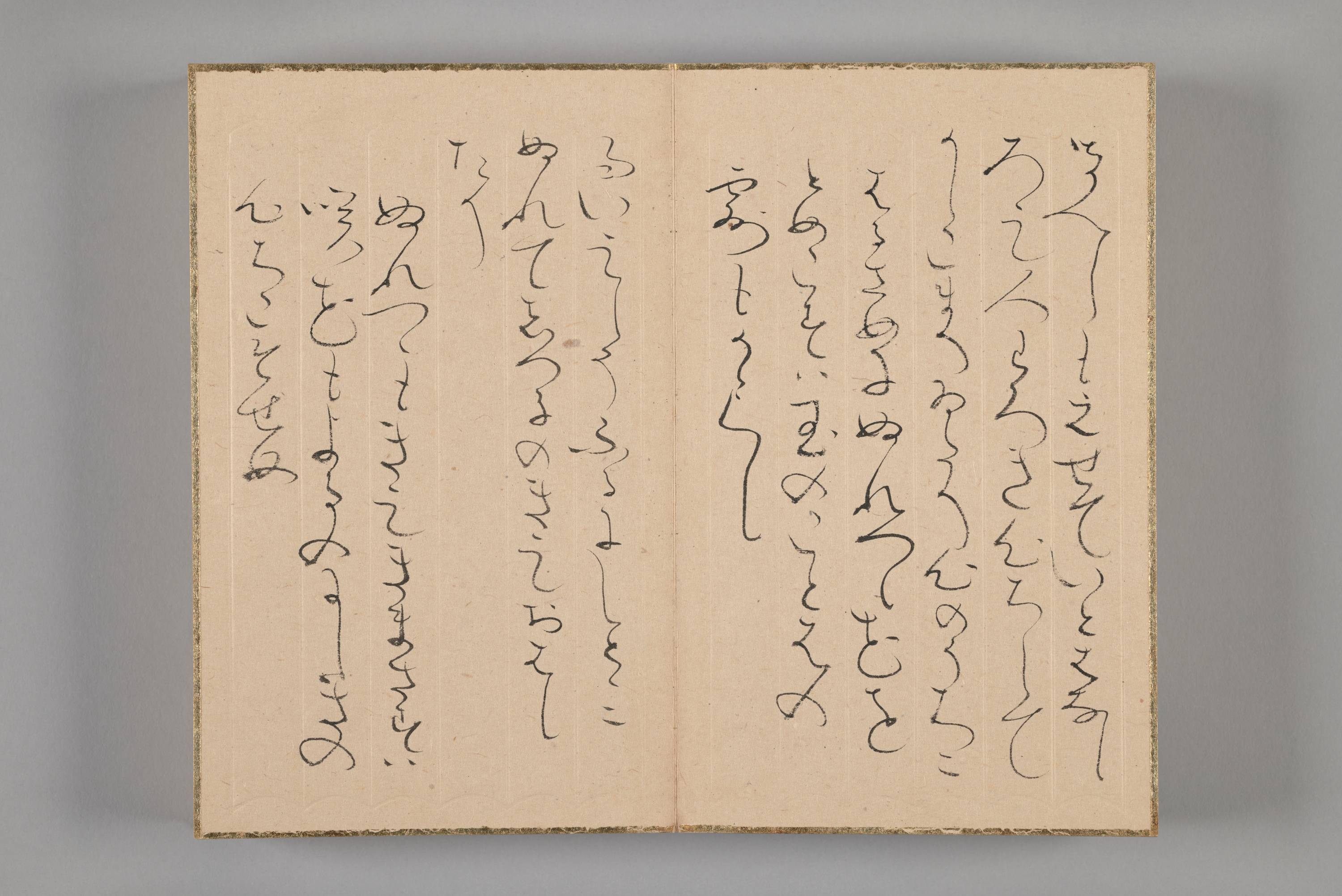

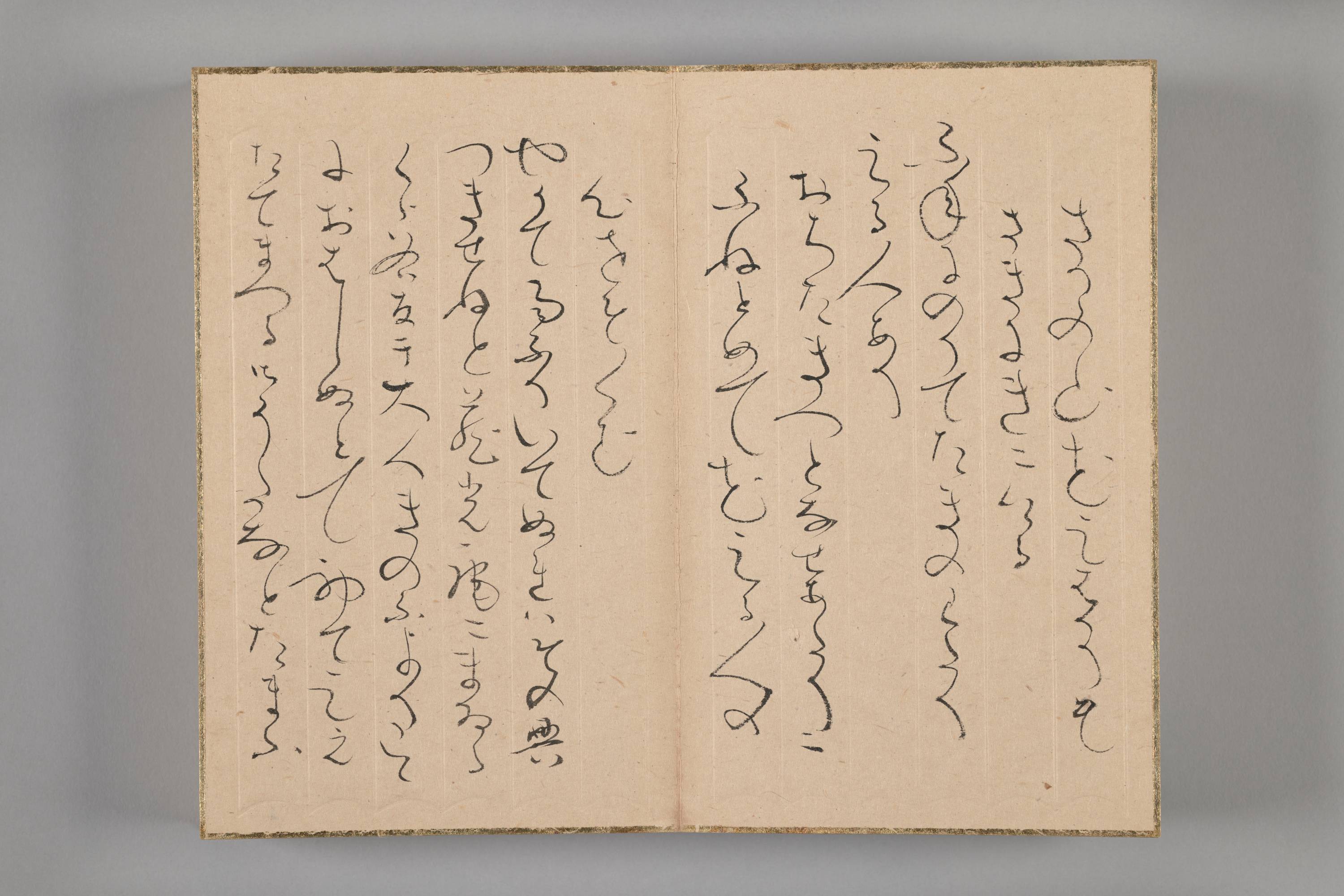

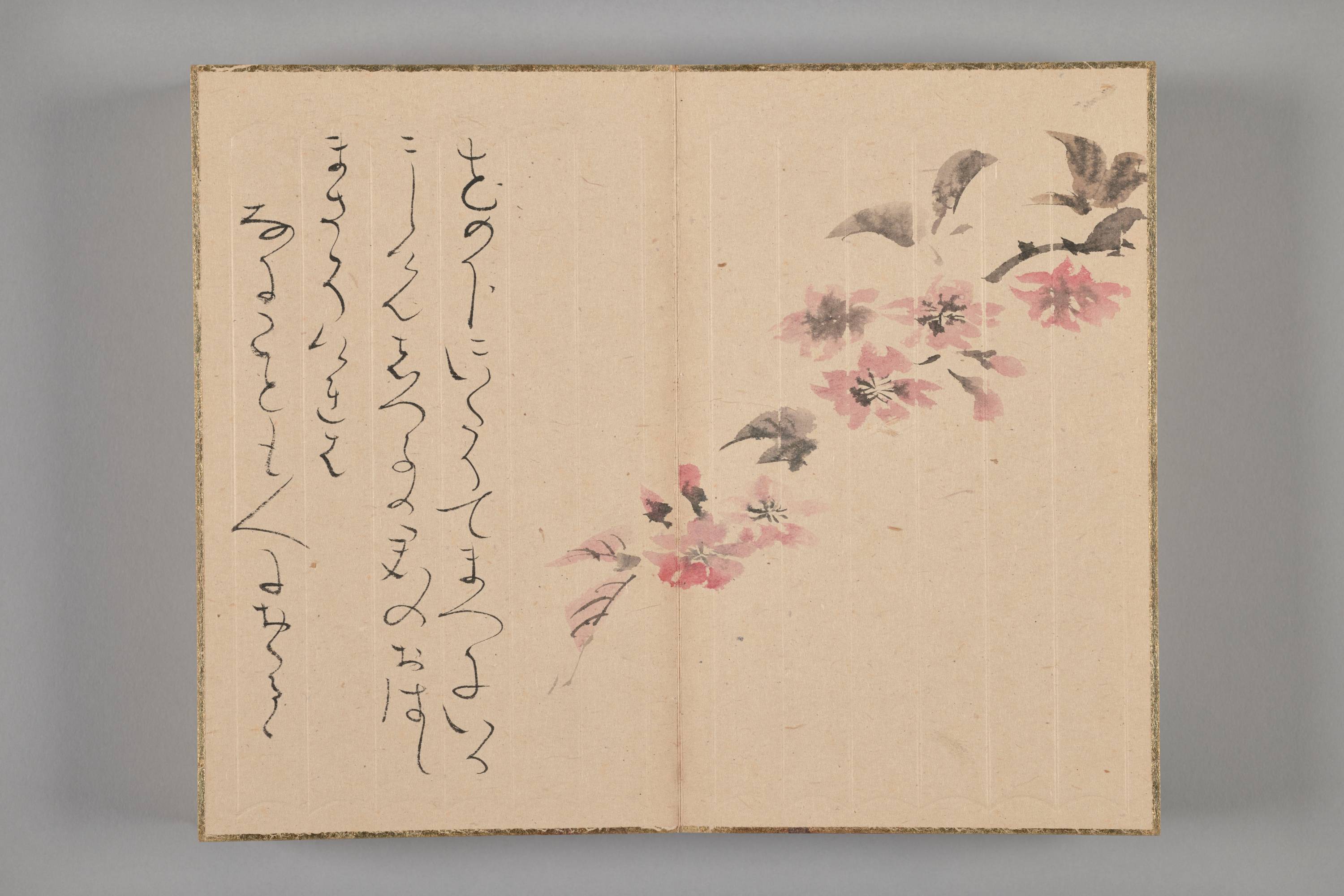

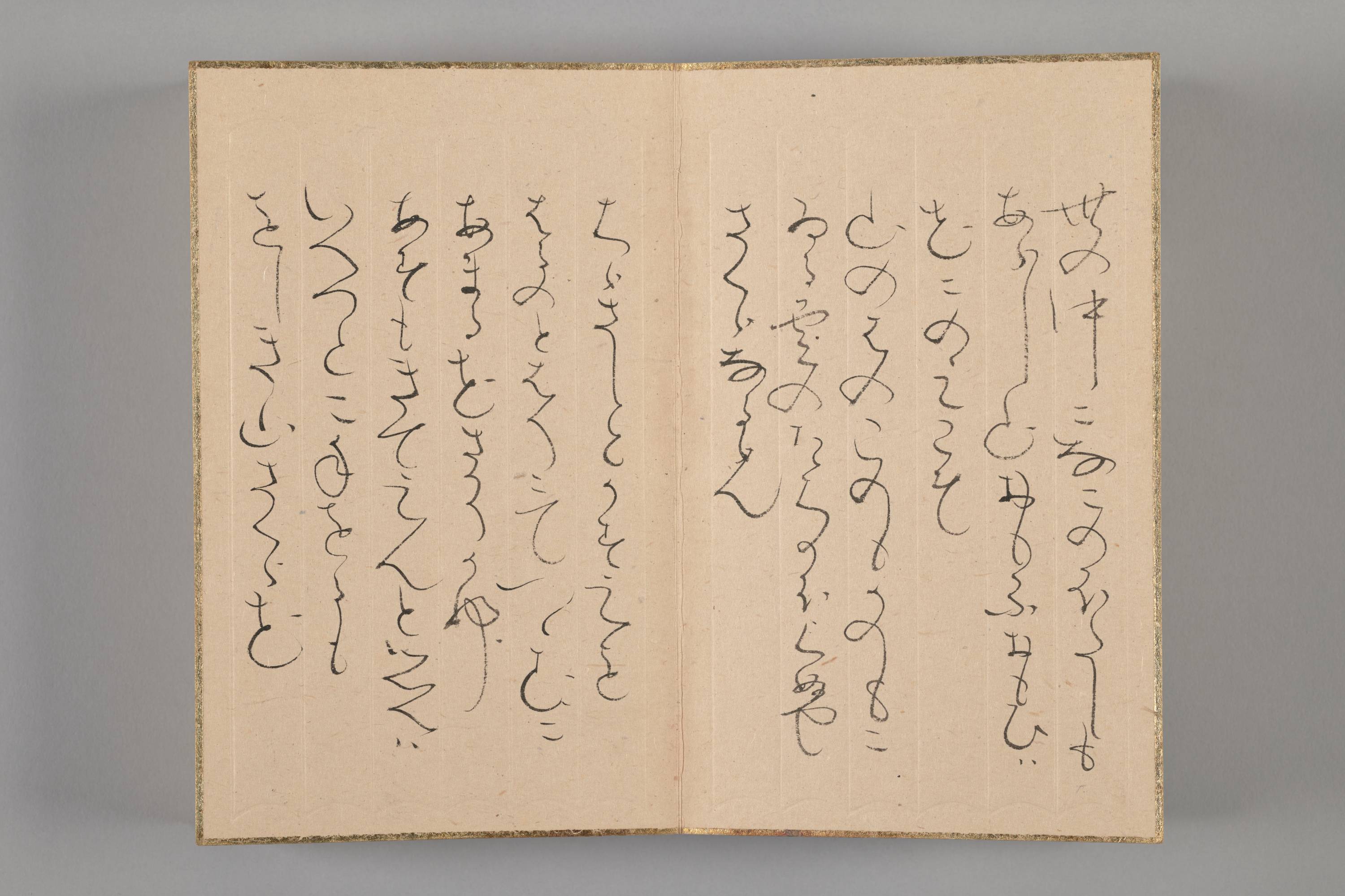

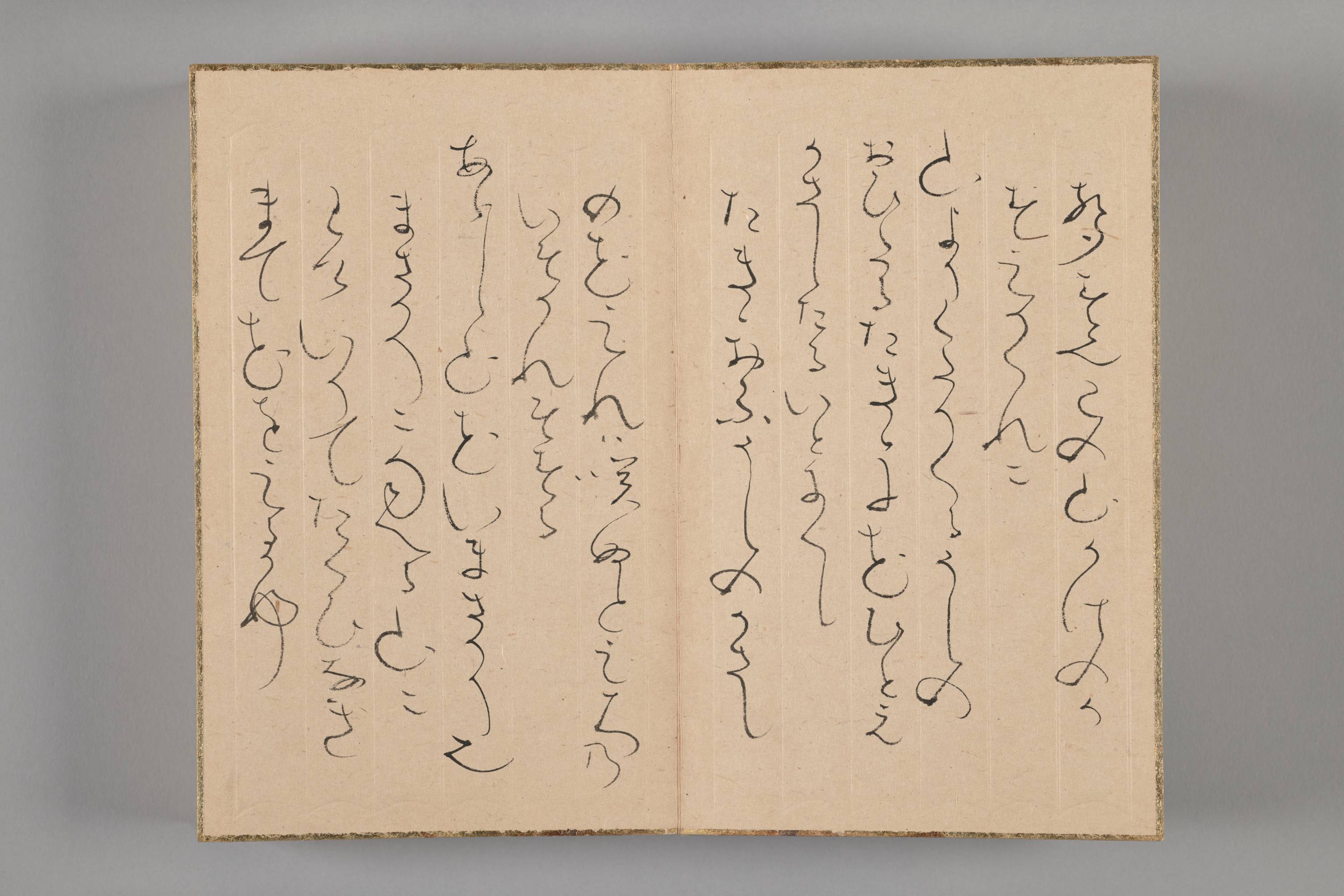

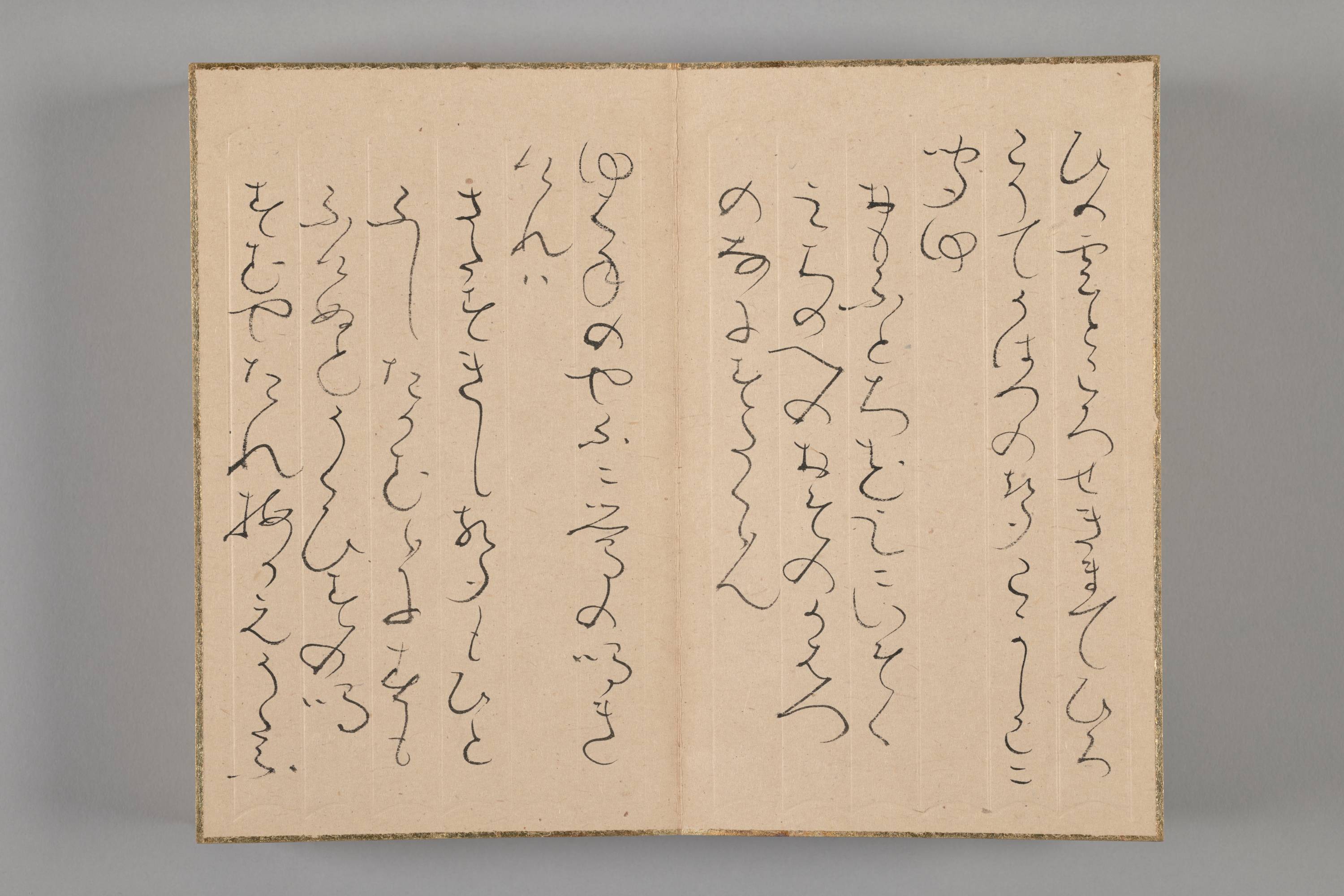

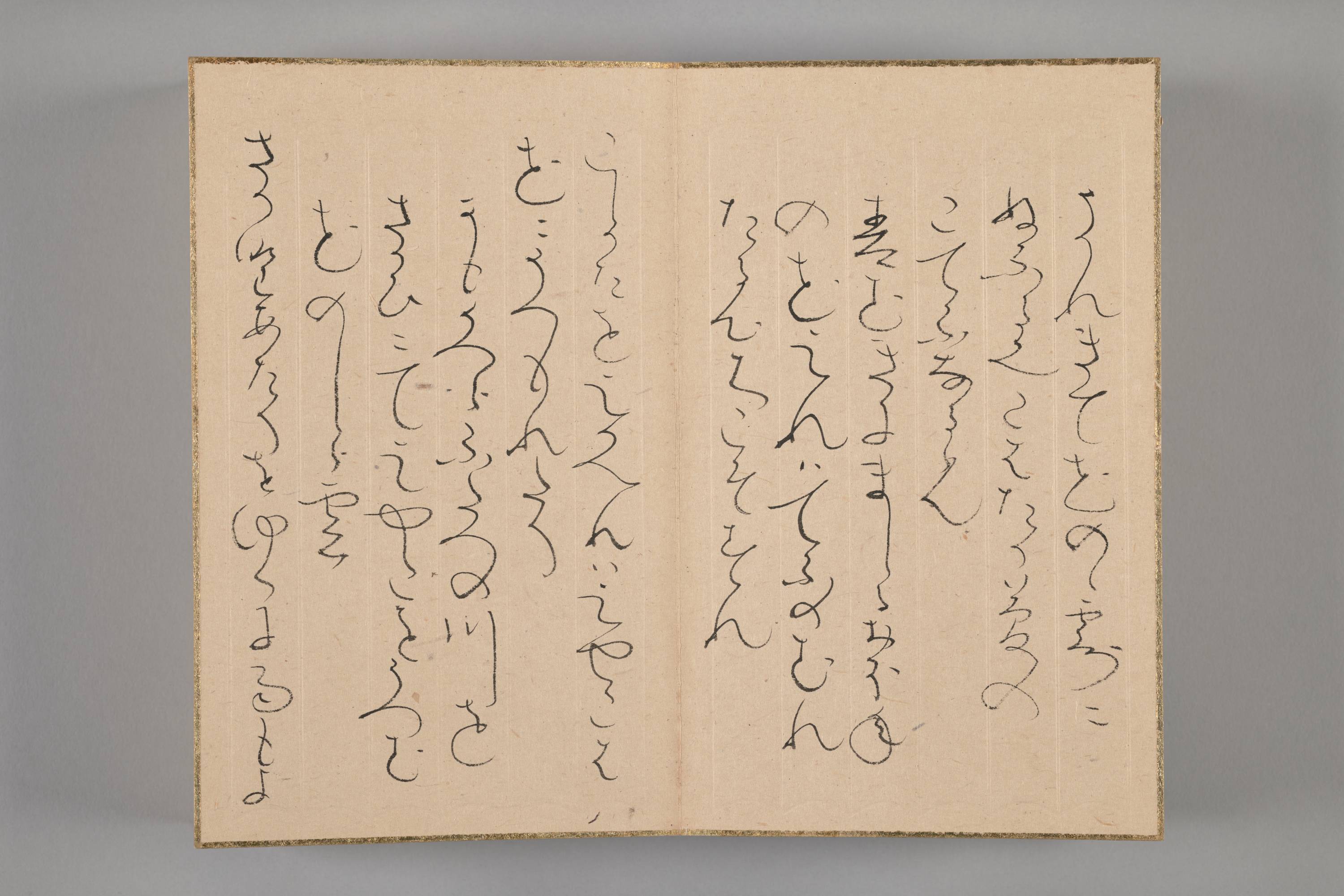

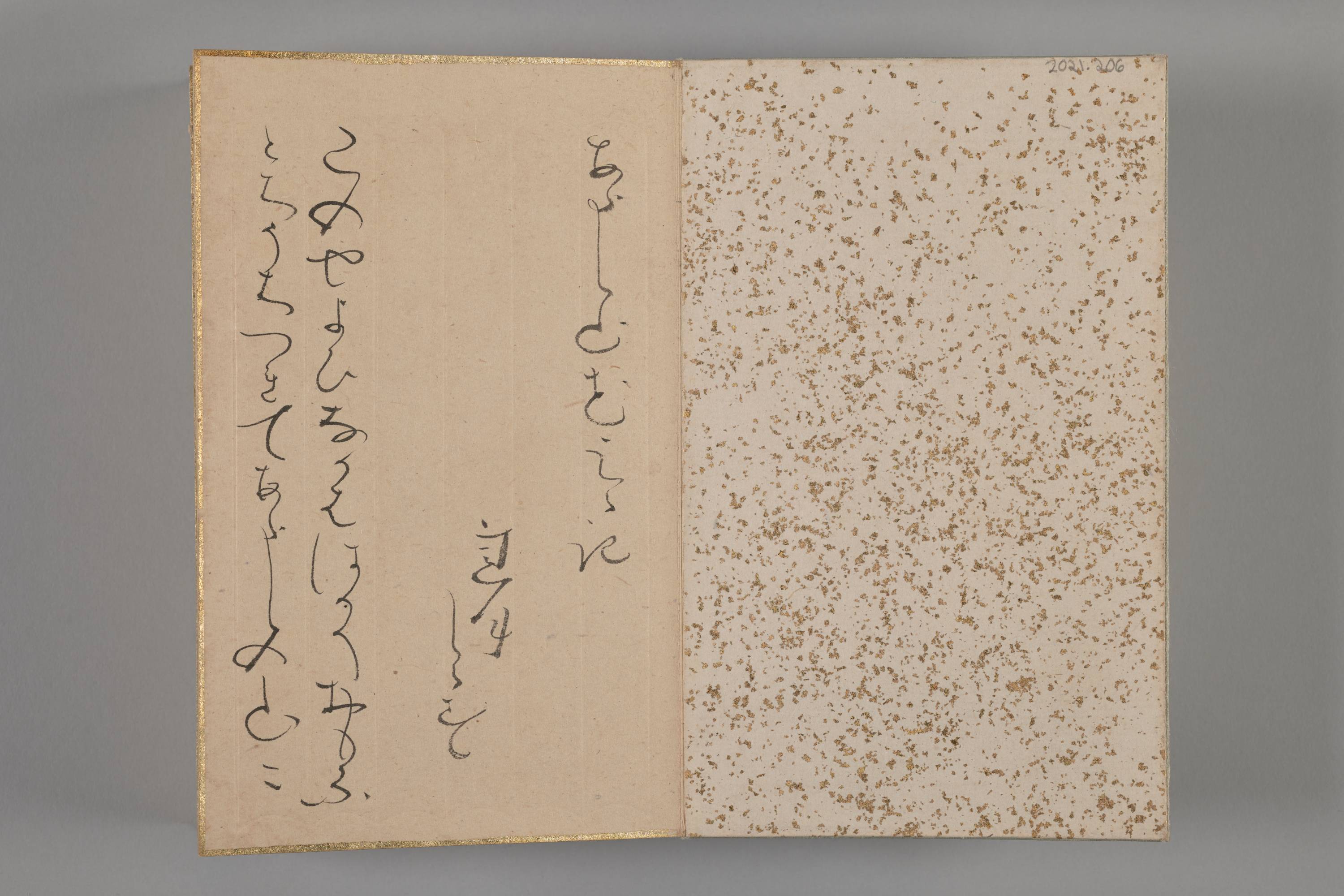

This travel journal recounts Ōtagaki Rengetsu’s visit to Arashiyama, a district to the west of Kyoto. Freely brushed poetry is occasionally punctuated by offhand and charming illustrations. Simple forms outline a cluster of flowers. A few lines gather into a torii, a traditional Japanese gate, overtaken by vegetation. This account offers a rare and intimate glimpse into the artist’s personal musings. It must not have been a long trip since Rengetsu left a good part of the album blank.

Princess Umenomiya, daughter of Emperor Gomizuno-o (1596–1680), took the tonsure at age twenty-two, changing her name to Bunchi. She later founded a temple, which functioned as a training center for women.

The calligraphy reads “Bodhisattva of Myriad Acts of Compassion,” the Buddhist name for the principal deity of a Shinto shrine in Nara. By writing this myōgō (names of Buddhist deities as invocations), Bunchi performed a devotional act, accumulating karmic merit.

ŌISHI JUNKYŌ 大石順教 (1888–1968)

In her youth, Ōishi Yone was establishing her career as a geigi dancer. Her stage name was Tsumakichi. When she was seventeen, her adoptive father went on a murderous rampage, killing six members of the teahouse where she worked and severing both her arms.

After a long journey to recovery, she observed a bird feeding chicks with its beak. Inspired, she learned to paint and write calligraphy using her mouth. She deftly maneuvered the brush with her lips in astonishing control.

At the age of forty-five, she took the tonsure as a Buddhist nun, adopting the name Junkyō. Junkyō later founded a Buddhist temple where she devoted herself to art, Buddhism, and counseling people with disabilities, advocating for independence and resolve.

RYŌNEN GENSŌ 了然元総

Born into an aristocratic family as the daughter of a lady-in-waiting, Ryōnen Gensō spent her early years in the Inner Chambers. At the age of seventeen, she married a courtier. Ten years later, she took the tonsure and became a Buddhist nun.

Wishing to join as a disciple of a famous Ōbaku Zen monk, she traveled to Edo (Tokyo). However, the monk turned her away on the pretext that her beauty would distract male disciples.

In a stark show of determination, she used a searing iron to disfigure her face. Only when proving this degree of devoutness to her faith was she finally accepted into the order.

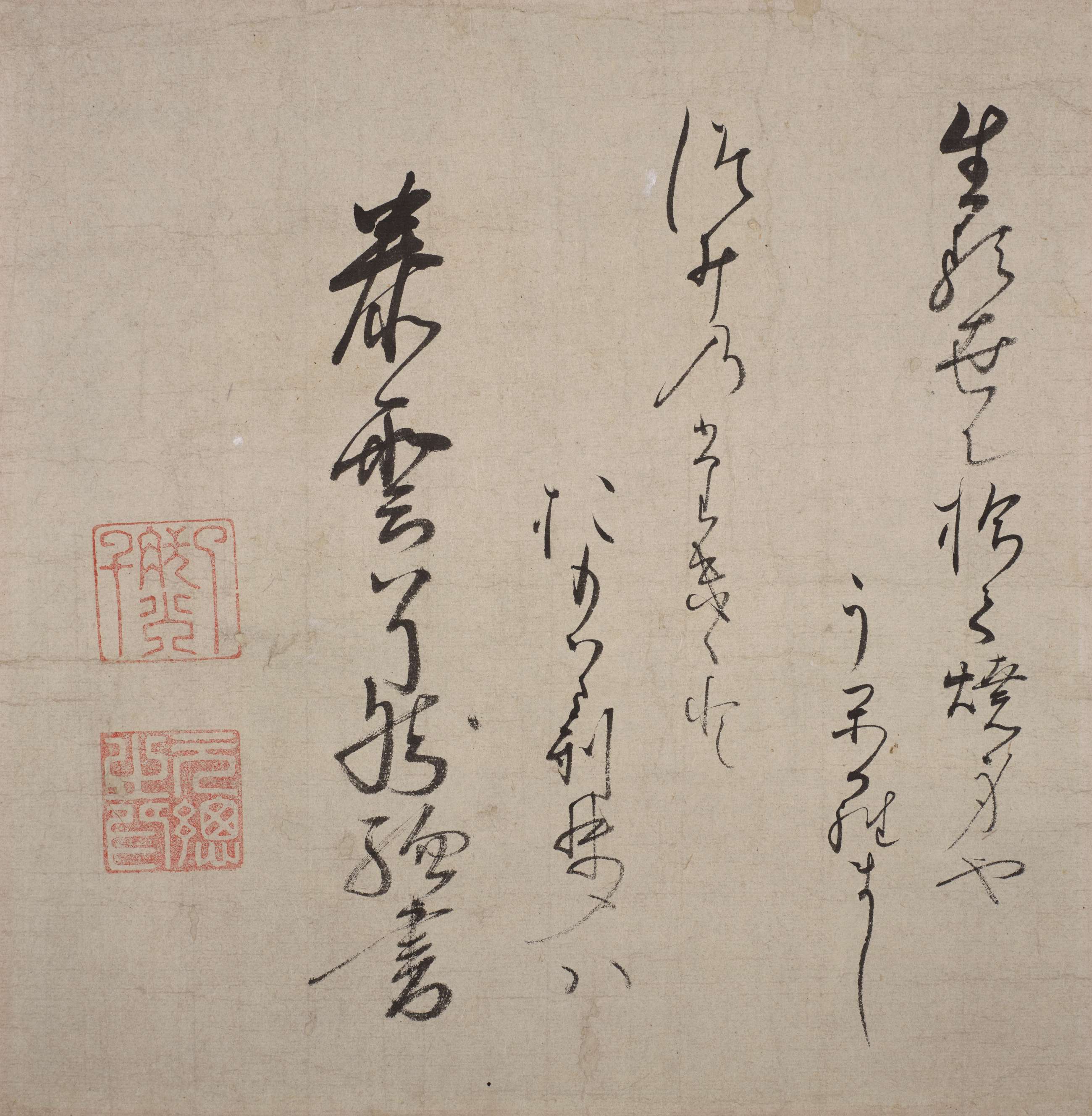

This poem was written shortly after this turning point. It reads:

“In this living world,

my flesh is burned and thrown away.

I would be wretched

if I did not think of it as kindling that burns away my sins.