Ōtagaki Rengetsu’s Buddhist Poetics: Gender and Materiality

- Melissa McCormick

Poet, painter, and ceramicist Ōtagaki Rengetsu (太田垣蓮月) (1791–1875) and her artwork and status as a Jōdo Buddhist nun challenge assumptions concerning the gender identities of historical subjects. Active for over fifty years as an artist after taking Buddhist vows, Rengetsu, and other nun artists of her era, demands a nuanced approach to gender beyond static notions of “female” and “male.” Since she removed physical markers of conventional lay femininity—shaving her head, donning simple robes, taking the name Rengetsu (Lotus Moon)—her identity can be understood through a contextualized lens that accommodates the historically contingent nature of gender categories. Although aspects of her artistic identity and self-expression may seem straightforward, Rengetsu’s work often demonstrates an engagement with a Buddhist philosophical tradition that questions the very nature of the self and artistic subjectivity.

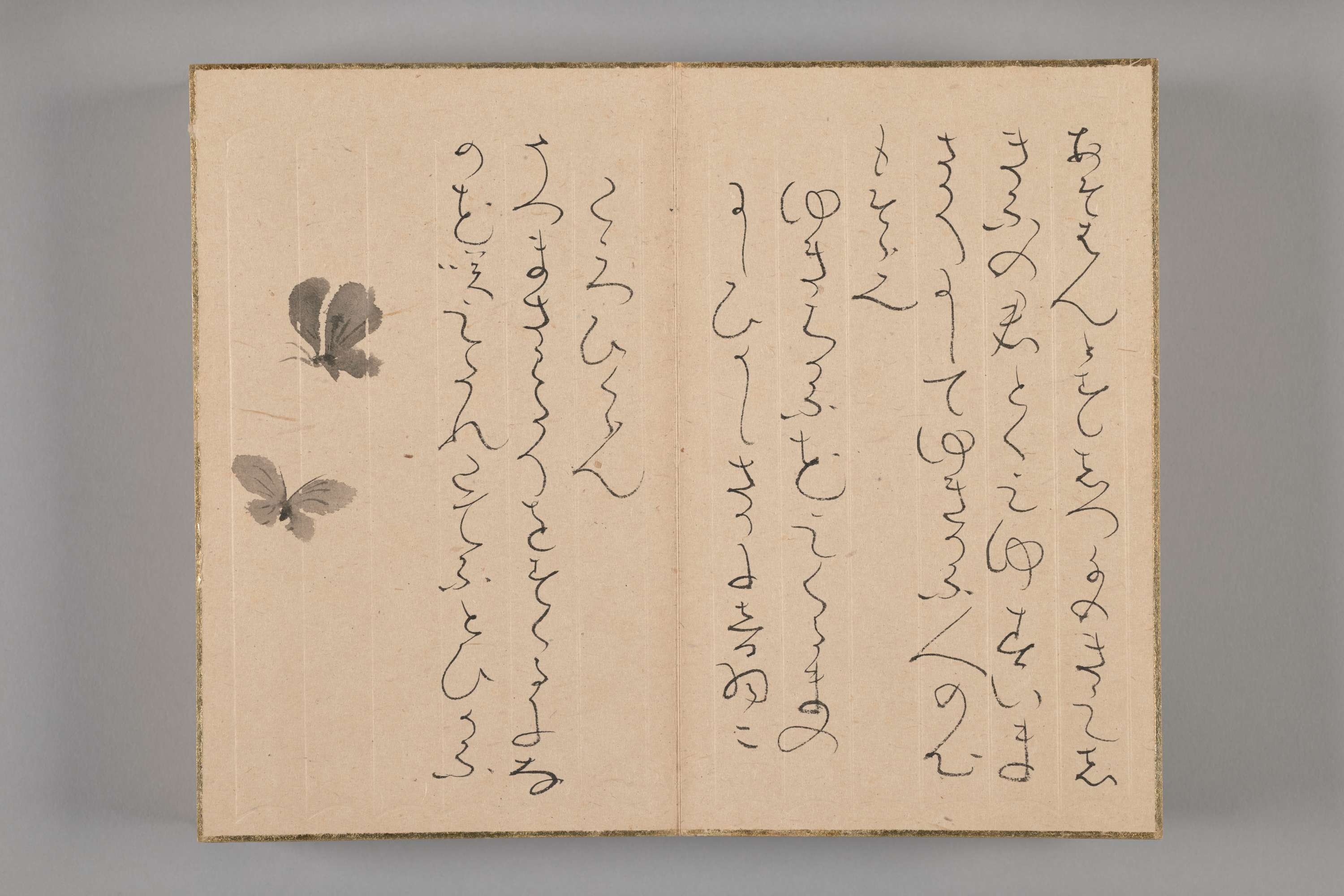

Close readings of certain works by Rengetsu suggest that she composed her poetry by engaging in an intertextual relationship with past poets that brings these issues of gender and Buddhism to the surface. In particular, Rengetsu looked to the monk-poet Saigyō (1118–1190) and the poet Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694), who himself used Saigyō as a model. An allusion to Saigyō’s verse can even be read into Rengetsu’s most famous poem, represented in the exhibition Her Brush by an elegant poem-picture hanging scroll (fig. 1). Similarly, the role and rhetoric of travel in the work of male predecessors is crucial to Rengetsu’s poetry and warrants an examination of her travel journal to Arashiyama, in the exhibition (fig. 2), along these lines. Even beyond poetic allusion and approach, Rengetsu seems to have modelled her poetic persona on these past poets, suggesting among other things a self-fashioning of identity through literary lineage unbound by gender, as least in the poetic imagination.1

While Rengetsu’s status as a Buddhist nun differentiated her from lay women and impacted her ability to posit herself rhetorically as Saigyō or Bashō reborn, how did it shape her notion of poetics? Do Rengetsu’s works demonstrate, for example, the influence of a Buddhist aesthetic, which would foreground issues of the nonself or the interrogation of phenomenal form? Her ceramics, such as the sake decanter in the exhibition (fig. 3), would seem to project the opposite in their tangible, earthy materiality. And yet Rengetsu’s inscriptive practices on certain three-dimensional objects can result in work that projects an air of the insubstantial. Rengetsu’s work is ripe for analysis regarding the connection between its haptic qualities and Buddhist materiality. Her incorporation of past poetic personae and Buddhist aesthetics raises compelling questions about the intertextuality and material properties of her artifactual poetics.

Watch Melissa McCormick's Symposium Presentation

-

In addition to Saigyō and Bashō, Rengetsu had nun predecessors to emulate, such as Tagami Kikusha (1753–1826), who studied haikai with a teacher in the Bashō lineage and who famously reenacted, in an inverse manner, the journey that Bashō documented in his Narrow Road to the North (Oku no hosomichi, 1702). See Oka Masako ed., Unyū no ama Tagami Kikusha (Yamaguchi: Kikusha Kenshōkai, 2004); and Rebecca Corbett, “Crafting Identity as a Tea Practitioner in Early Modern Japan: Ōtagaki Rengetsu and Tagami Kikusha,” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal, no. 47 (2014): 3–27. ↩︎