Shining Light on Art by Japanese Buddhist Nuns

- Patricia Fister

I have been engaged in researching women artists for nearly four decades, and in the past twenty-five years, I have focused particularly on Zen Buddhist nuns. This brief overview of my personal journey recounts some of the obstacles and opportunities I have encountered and considers how they shaped my research approach and philosophy. Imperial convents contain a treasure trove of objects and documents, but like some other institutions and private collections in Japan, they have been reluctant to open their doors to scholars.

When I began in this field, very little was published on Japanese women artists, much less nun-artists, so the first step was gathering source materials. With permission, I photographed the objects and documents I was shown in convents and slowly created a private database. Because most of the convent collections are not cataloged, it has been exciting for me to view them in their “original homes.” Studying collections in situ is completely different from studying objects stored in museums or published in books. I have also had the rare opportunity to observe not only how objects are used but also the nuns’ attitudes toward them. For example, most present-day abbesses are adamant that Buddhist paintings and sculptures should not be referred to as art but rather be considered as religious objects, leading me to rethink the question of what constitutes art. I now look at objects from a slightly different perspective than I was taught in university art history courses, and I pay more attention to the vocabulary I use when writing about them.

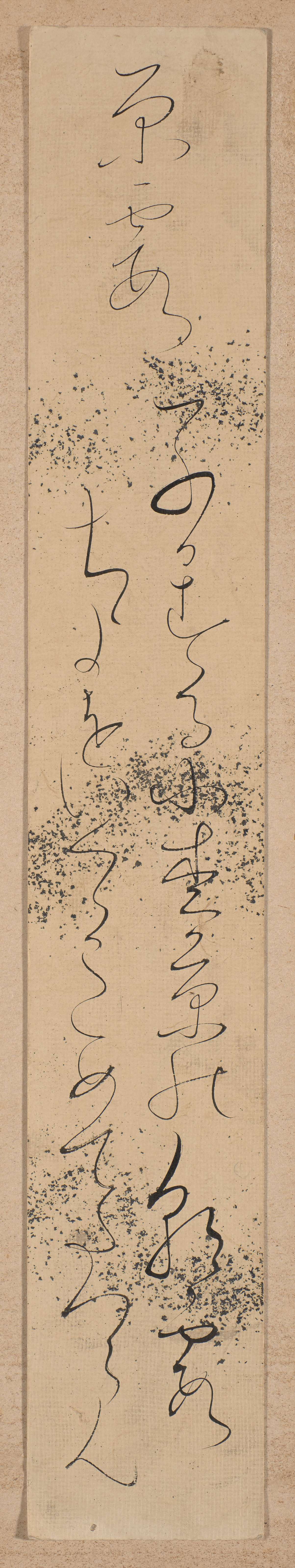

As I surveyed convent collections, I was constantly astounded at the diversity of objects made by imperial nuns, who grew up with culture and art as a vital part of their lives. Among them are chinsō (sculpted and painted portraits of Zen masters), paintings of Buddhist deities and secular subjects, calligraphy, embroidery, and other unique items. Some nuns left writings giving some information about their lives, religious aspirations, and artistic practices. I feel strongly that one needs to build a foundation of works as well as documents to ponder and analyze before drawing any meaningful conclusions.

I am particularly interested in nuns’ intentions and the role or function of creating in their lives. At what point in their religious careers did they begin to make things, for what purpose, and for whom were these objects created? What Buddhist doctrines or spiritual goals were the nuns seeking to express? Why did they choose specific models? I believe that the words of the Lotus Sutra were integral, for it taught that producing and dedicating art was a way of attaining the Buddha way. Consequently, nuns were inspired to take up a brush, or clay, or even powdered incense to create devotional imagery. The scarcity of biographical information for some of the abbesses of major convents made me realize all the more that the tangible objects they themselves created represent an important part of their legacy.

In the course of my research, I discovered one Kyoto convent that had been “forgotten.” I have also tangled with an important thirteenth-century nun, Mugai Nyodai (無外如大), whose identity has become terribly confused: over the centuries her biography was merged with those of two other women. Both the “resurrection” of Zuiryūji (瑞龍寺) convent as well as an ongoing project to restore Mugai Nyodai’s true identity merit further discussion.

While conducting this research in convent collections, the urgent need for conservation and preservation, too, became evident to me. In fact, in my mind now, it goes hand in hand with research. In other words, it is crucial not just to publish the results of one’s studies but to give back as well. As an example, I aided one temple in getting four important portrait sculptures of nuns restored. In turn, fascinating discoveries were made during that conservation process.

Finally, let us briefly consider the role of gender—one of the themes of the Denver exhibition and symposium—in monastic art. I am often asked to define what aspects distinguished the devotional practices and objects made by nuns from those of male clerics. I usually respond by first pointing out the prevalence of Kannon, the Goddess of Mercy, imagery among nun-artists. Needlework, traditionally considered a pastime for women, was also common in Japan’s imperial convents, where nuns often sewed their own robes and surplices. The nun Bunchi (文智 1619–1697) created some unique devotional objects by embroidering phrases from Buddhist texts onto silk and mounting them on small plaques. Other nuns used hair to make devotional objects. Arguments have been made that the combination of fragments of women’s bodies (hair) with a womanly skill (embroidery) represents a gendered form of religious practice not found among their male monastic counterparts.

Research focused on Buddhist nuns and convents is growing, not so much in art history but in other fields such as history, literature, and religious studies. All are necessary for us to form a comprehensive picture. The arts of Japanese Buddhist nuns deserve to be more well known than they are, and the Denver exhibition and symposium provide welcome opportunities to introduce a selected body of work to the general public.