On the Fong-Johnstone Study Collection and the Power of Access

- Einor Cervone, Associate Curator of Arts of Asia, Denver Art Museum

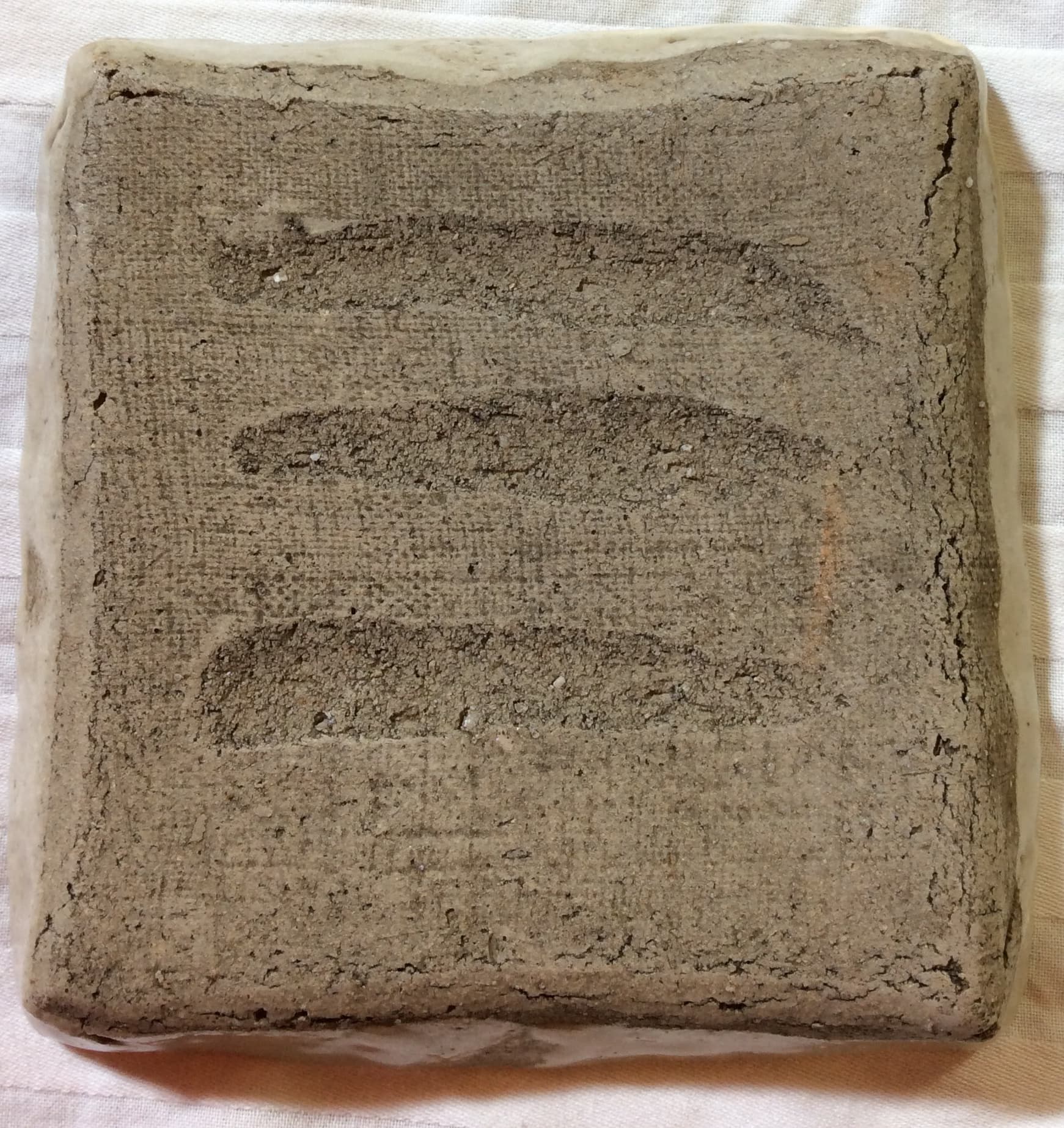

A slapdash fissure stretches into a grimace beneath two burrowed cavities—a pair of gaping eyes—pressed into groggy shigaraki clay (fig. 1). Simple, coarse, unglazed. Almost insignificant. But then, a metallic glimmer draws the eye. Gold and lacquer kintsugi, lovingly applied to mend a crack, discloses how treasured a possession this tortoise-shaped kōgō (incense box) must have been. Notwithstanding its undeniable charm, how was its earthy material, hastily pressed onto a mold, valued above gold? Turning it over, three finger-wide grooves drag vertically from chin to tail. Through them, a signature emerges: Rengetsu (fig. 1b).

Oscillating between mass production and prized rarity, this tortoise kōgō sneers at such proscriptive divides as those of professional and literati art. Rengetsu (Lotus Moon) was the ordained name of the Buddhist nun and artist-cum-celebrity Ōtagaki Rengetsu (太田垣蓮月 1791–1875). Her painting, calligraphy, and ceramics were so coveted that she could barely keep up with demand. She did not have her own kiln, relying instead on local networks. She churned out deceptively simple and heartachingly captivating ceramics. Her idiosyncratic style, unpolished and whimsical, came to be known as Rengetsu-style pottery, or Rengetsu-yaki.

The market—forever attentive—swiftly responded to this demand in kind with a flood of copies and forgeries already in the artist’s own lifetime. This plethora of Rengetsu-yaki wares has long challenged art historians and connoisseurs in assessing the artist’s oeuvre. At the same time, these idiomatic works hold an equally important key to better understanding the artist, her life, and her work.

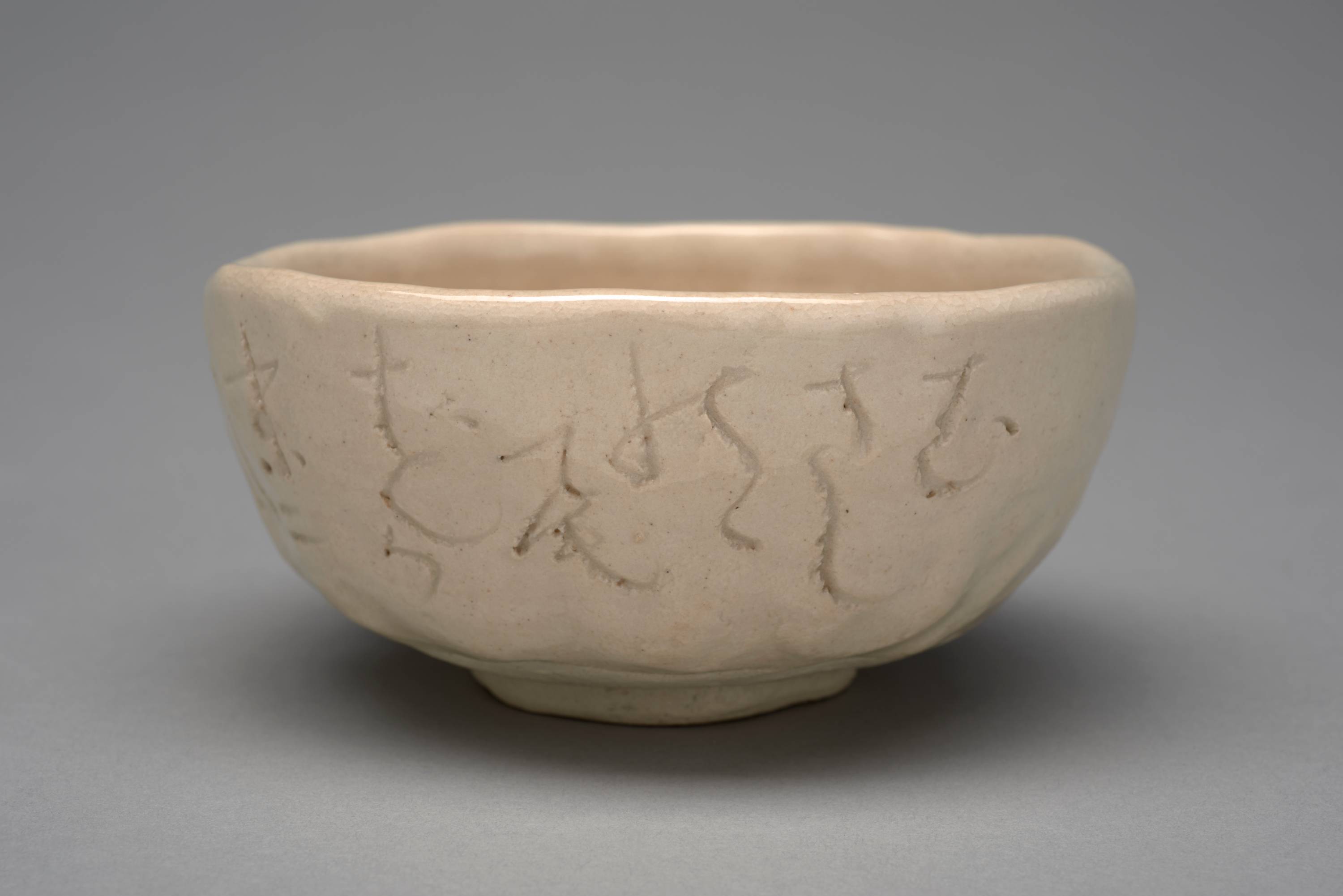

Emulations of Rengetsu’s signature style range from outright forgeries (e.g., figs. 2–3) to pieces that, as art historian Paul Berry has remarked, were never intended to deceive but instead were a nod to her work—an homage to the artist. Such, for instance, is this later incenser bearing an underglaze poem by Rengetsu and crowned with reticulated metal openwork (fig. 4). Its smooth and clear-overglazed surface indicates it was thrown on a wheel. It thereby does not attempt to imitate Rengetsu’s hand-built process. It is not a forgery; neither is it an authentic work by Rengetsu herself. It is an “honest copy.” It lives in the liminal space, somewhere on the richly gradated spectrum of idiomatic artmaking (a forthcoming video will feature a discussion of two Rengetsu-yaki teabowls by the artist Kuroda Kōryō (黒田光良 1823–1895).

Belying the elaborate role of copying in East Asian art, the very classification draws an implicit bias in Euro-American art-historical discourse. Granted, some copies are forgeries made explicitly to be passed off as authentic. The act of copying, though, is more nuanced. It is intrinsic to the artist’s technical maturation. It is a way of constructing and finessing one’s artistic voice, of capturing an admired master’s technique—even their spirit. It weaves a visual dialogue with one’s predecessors, artistic lineages, and visual culture—whether contemporaneous or historical. Producing a copy can be an expression of appreciation, a claim to having mastered (or even surpassed) said precursor, or anything in between.

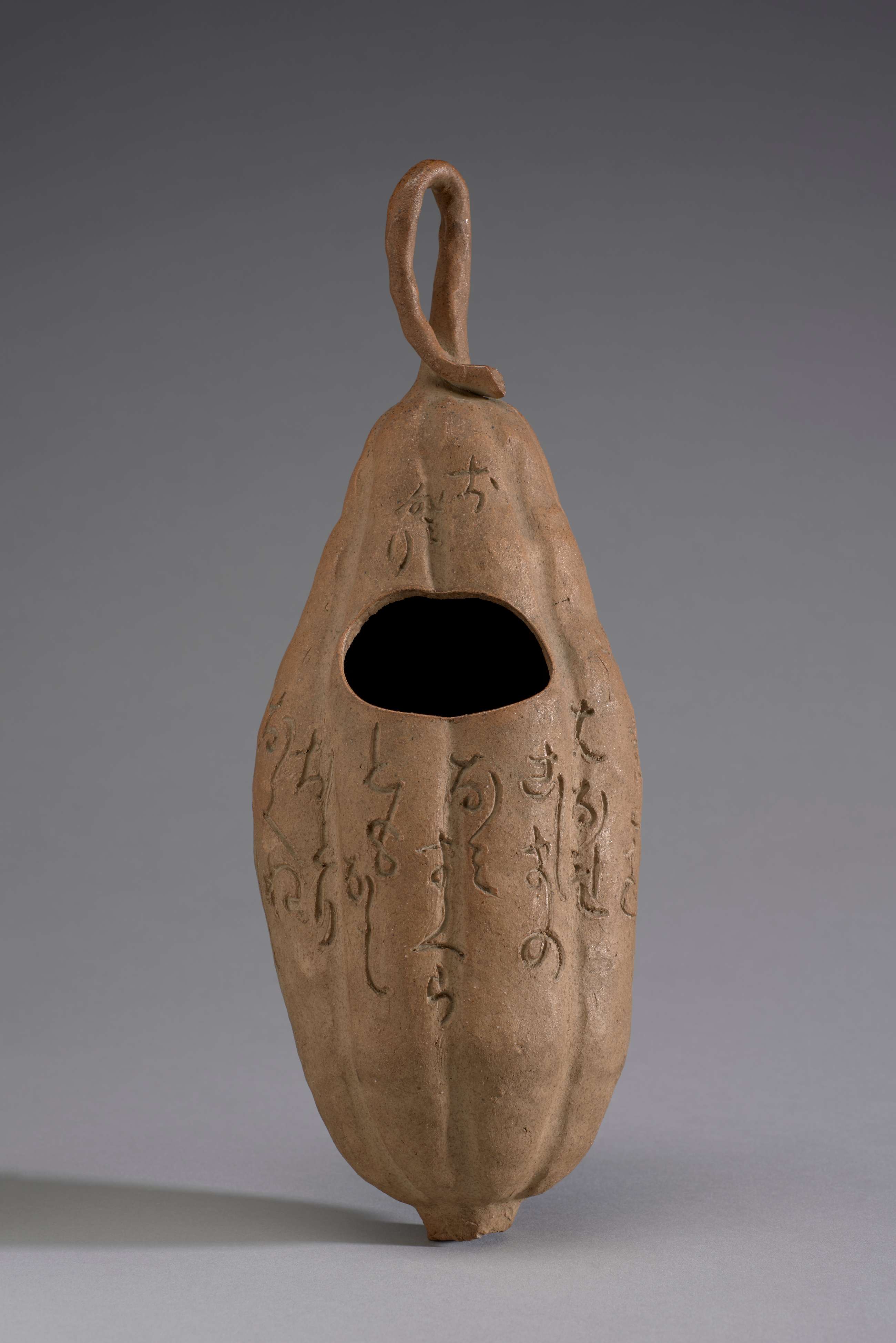

Dismissing idiomatic art can be likened, perhaps, to removing archeological artifacts from an excavation site without taking stock and documenting the context within which they were found. In the case of Rengetsu, the legacy that emanated from and orbited her lode star can shed light not only on her reception throughout the ages but on her practice as well. Take, for instance, these two hanging vases (hana-ike) (figs. 5–6). Both are Rengetsu-yaki, fashioned into bulbous gourds, wonky and humorous. At first glance one might be tempted to attribute both to the artist. Looking closely, though, the cracks begin to show.

A lone pine awaits me

its needles chestnut brown—

were someone here to greet me

I’d present a souvenir from Miyako

happily saying: “Here!”

くりいろの

あれはの松の

人ならば

都のつとに

いざといはましを

Having left my hometown

sleeping on a pillow of waves

as I travel a far-flung island . . .

how sad the cries

of a friendless plover.

ふるさとを

はなれ小島の

浪まくら

ともなし千鳥

鳴音かなしも

We will refer to the first hana-ike as Lone Pine and to the second as Friendless Plover. While both poems were indeed composed by Rengetsu, the calligraphy reveals a discrepancy in style and technique. The poem gracing Lone Pine is rendered in a confident hand with elegant kana and lithe curves. The stylus pushed through the soft clay, parting it smoothly, leaving clean and crisp ridges that are further accentuated by the darkened edges from the firing process (fig. 7).

The calligraphy on Friendless Plover, however, is more belabored and uncertain. The kana drags and tears at the clay, leaving a rugged trail in its furrows. It is weighed down by forced flourishes and overly accented curlicues (fig. 8), and it lacks the balanced cadence of Lone Pine.

Nowhere does this discrepancy emerge more clearly than in the incised signatures. The lightness and natural undulation of line in Lone Pine (fig. 9) contrasts sharply with the clunky kanji on Friendless Plover (fig. 10).

Once again, the objects’ backs disclose important information (figs. 11 and 12). Placed side by side, it is evident that the cut-out apertures, intended to accommodate a hook for hanging, were not handled with the same attention.

Friendless Plover bears a rectangular cutout with rugged, uneven edges. This haphazard and unpolished treatment is in line with Rengetsu’s style; however, here lies a clue: hana-ike are functional wares. They were intended to be hung in a tokonoma (display niche) and often contained flower arrangements (ikebana). The hook cutout therefore was not a forgiving element in the ware and would have needed to be smoothed out and leveled, so as not to snag or hang askew. Lone Pine’s hook aperture fulfills these requirements with a clean, oval finish. It hangs naturally and perfectly balanced.

Finally, gathering both objects and turning them in one’s hands, studying their haptic qualities, their textures, and balance—one, ponderous and unwieldy, weighed down by poorly distributed matter; the other, as if fashioned for your hand alone, perfectly balanced, buoyant, almost. As if lending one’s ear to a whisper, handling an object can divulge its innermost secrets.

When assessed on its own, Friendless Plover can certainly pass as a genuine work by Rengetsu. It is only by scrutinizing it against comparable works from the artist’s oeuvre and within the broader context of its production that incongruities begin to emerge. Ultimately, visual observation alone cannot offer complete and accurate information for gauging a work of art. In order to arrive at the most accurate conclusions, one must take into account tactility, weight, balance, and distribution of clay—sometimes even sound and smell—as these all hold vital information.

In recent decades, opportunities to access this type of information have been steadily decreasing. As James Watt, Curator Emeritus at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, once shared in a conversation some years ago, while past generations of curators and scholars enjoyed access to museum storerooms, learning with their hands, eyes, and noses by reviewing roomfuls of artworks, it is rarely the case today. Indeed, most art history students will get to handle no more than a handful of artworks in their training. Those pursuing academic careers will likely be poorly equipped to approach questions of connoisseurship.

The sobering realization that this coming generation of scholars will have little access to artwork has been the force behind the Fong-Johnstone Collection and Study Collection initiative. The gift, numbering more than five hundred objects—both copies and originals—will be made available to specialists, educators, and students. The Denver Art Museum is committed to leveraging the collection to raise awareness, offer accessibility, and advance the study of connoisseurship in its two focus areas: Ōbaku Zen painting and women artists from early modern and modern Japan. This is done with the conviction that, together, idiomatic and original artworks can help shed light on a more complete story of art history.

And so, three inexplicable grooves on a late set of Rengetsu-yaki plates may speak not only to the artist’s centuries-long fame but also divulge a recognition of the powerful statement they make (fig. 13). By drawing three fingers across the clay—a stylized nod to pressing the material into the mold and the scraping off excess clay—Rengetsu acknowledges her medium of choice and at the same time she commemorates her intimate touch of the clay. The later set mimics the famous detail seen on the mold-pressed tortoise kōgō, but it does so on the back of the plates and over an impression of a slump mold’s coarse fabric. In other words, opposite to where it should have been placed. This misunderstanding of the process and intent inadvertently exposes the set of plates to be a copy, foiling an attempt to replicate the artist’s personal touch.

And is it not that, ultimately, that draws us to this mystery? The artist’s touch. Her mark.