Calligraphy, Poems, and Paintings: by Japanese Buddhist Nuns

- Patricia Fister

Why is it that people are fascinated by the idea of nuns creating art? Is it because they expect nuns to express something different from “ordinary” artists, perhaps something spiritual? It was not unusual for Buddhist nuns in Japan to write poetry (waka, kanshi), names of sacred deities (myōgō), or single-character/single-line Zen maxims and to paint devotional images as well as secular subjects. Less common was the creation of sculpture or ceramics, but examples do exist.

This essay will explore what it meant for nuns in Japan to take up the brush or mold forms from clay. Motivations vary according to their background, religious sect and training, and personalities, just as women took the tonsure for diverse reasons. Some were “placed” in convents when they were young children, but those included in this exhibition all became ordained by their own free will. Some of them renounced worldly life out of pure religious commitment and became heads of temples, while others were only loosely affiliated with religious institutions, choosing not to cut secular ties completely in order to more freely pursue their literary and artistic interests. The Fong-Johnstone collection includes works by nuns affiliated with various Buddhist sects, ranging in date from the seventeenth to the late twentieth century, which provides an opportunity to study a representative sampling of their artistry. Some nuns were quite prolific, and their works can be readily found on the art market. Others were more pious and private in their endeavors, with the result that their works rarely went beyond the walls of their convents or related temples.

Exemplars of Austerity and Discipline: The Zen Nuns Bunchi and Ryōnen

Although separated in age by twenty-seven years, the lives of Daitsū Bunchi (大通文智 1619–1697) and Ryōnen Gensō (了然元総 1646–1711) overlap in several respects. Both were connected with the aristocratic Konoe family (a branch of the Fujiwara clan)1 and spent their early lives in the imperial palace, although their positions were quite different: Bunchi was the daughter of an emperor, and Ryōnen was the daughter of a lady-in-waiting to an imperial consort. Following social custom, both women entered arranged marriages in their teens. However, they left their husbands, took the tonsure, and committed themselves to rigorous Buddhist practice, studying with reputable Zen masters. Both eventually moved away from Kyoto and established temples elsewhere (Bunchi in Nara, Ryōnen in Edo [now Tokyo]). In the course of their practice and determination to abandon attachments to their female bodies, they engaged in harsh ascetic acts, which I will describe below.

Bunchi’s life has been written about extensively in English, so I will give only a brief account here.2 She was the first daughter of Emperor Gomizuno-o (1596–1680; ruled 1611–1629), and after a brief arranged marriage to her cousin at age thirteen, Bunchi (her childhood name was Ume no Miya) returned to the palace. Inspired by dharma talks by the Rinzai Zen priest Isshi Bunshu (1608–1646), she entreated her emperor father to allow her to take vows and become Isshi’s pupil. She was tonsured at the age of twenty-two, two years after her mother’s death (1640), and made the momentous decision to move out of the palace and take up residence in a small temple called Enshōji (Temple of Infinite Light) in northeastern Kyoto, where she spent the next fifteen years immersed in Zen studies and practice. She met with Priest Isshi occasionally, communicating with him primarily by letters until his death in 1646. Ten years later, Bunchi decided to move to Nara and set up a convent there, inspired in part by a dream in which she was told that she would find solace if she lived in the vicinity of the Ise, Hachiman, and Kasuga shrines.3 An uncle and a fellow disciple of Isshi assisted her with finding land, and in the 1660s, she established a convent called Enshōji south of the old capital of Nara, using the same name as her temple in Kyoto. The “new” Enshōji evolved into a strict training center for women, mostly from aristocratic families, and at one time she presided over a community of twenty nuns. The convent still exists today.

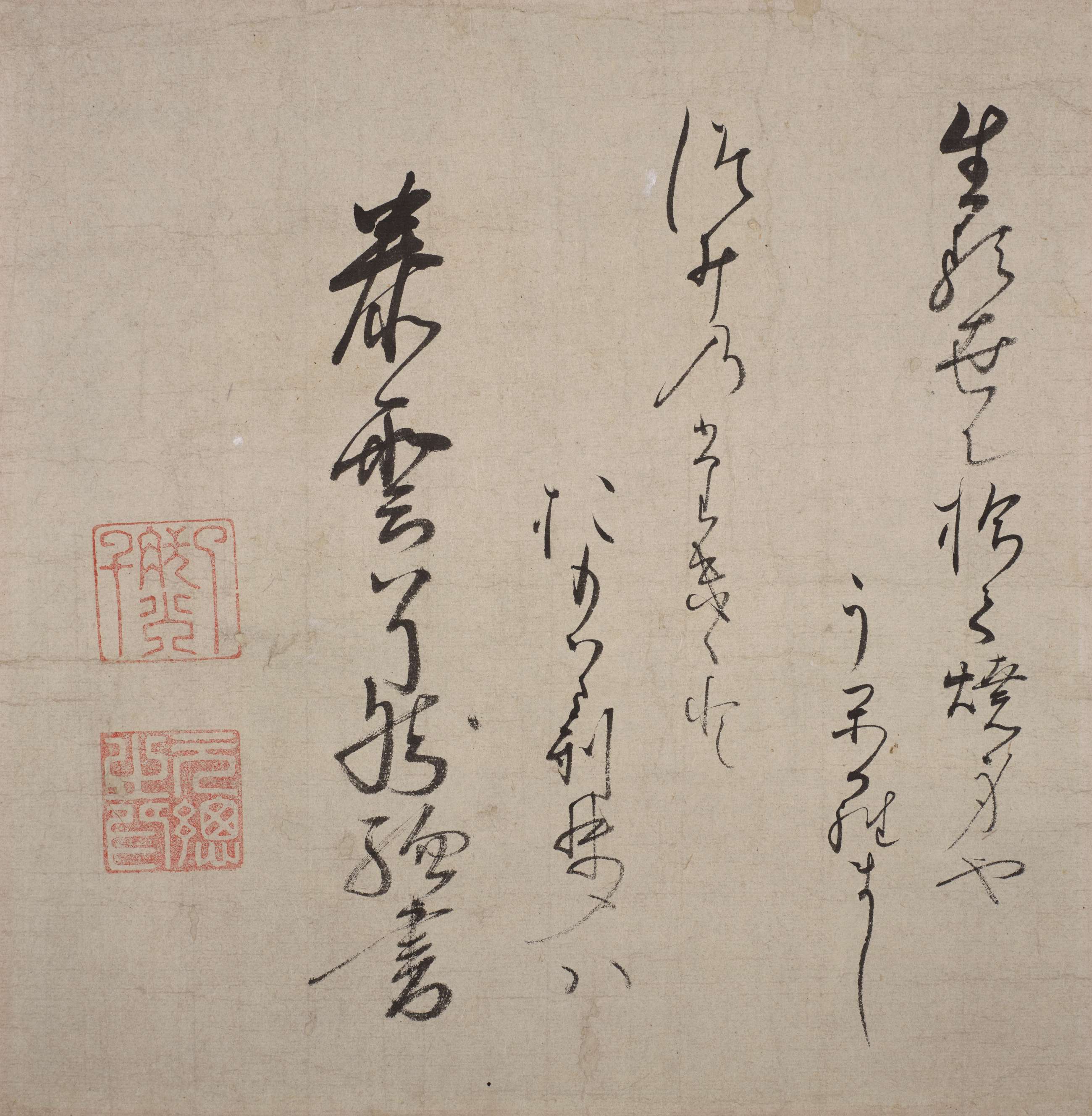

The Fong-Johnstone collection includes a single-line calligraphy by Bunchi (fig. 1), written in semi-cursive script, that reads “Jihi Mangyō Bosatsu” (literally, “Bodhisattva of Myriad Acts of Benevolence/Compassion”), which is a name for Kasuga Myōjin,4 long regarded as a spiritual protector of Buddhism in Nara and therefore referred to as a bodhisattva.5 While today we tend to think of Buddhism and Shinto as separate religions because of the forced separation of the two by the Meiji government in the late nineteenth century, in traditional Japan they were inextricably melded together. The written characters of a deity’s name are regarded as sacred; writing the name in this way—as a single line of calligraphy, a form known as myōgō—serves as a kind of invocation.6 The scroll is not signed, but the inscription on the accompanying box records that it is by the hand of Abbess Bunchi.

Bunchi ascribed the successful founding of her convent and teaching activities to the good will of Kasuga Myōjin, and she made daily offerings and prayers and encouraged her pupils to follow this practice.7 Her written vow (ganmon) to the Kasuga deity and a poem titled “Kasuga Shrine” are preserved at Enshōji, along with a small wooden Kasuga shrine constructed by her, complete with an avatar deer bearing an inscribed date of 1655, the year that she moved to Nara.8

The Buddhism that Bunchi taught at Enshōji was grounded in Rinzai Zen and tempered with elements from Shingon and Ritsu. Her own personal practice was marked by ascetic acts as she struggled to rid herself of worldly attachments and transcend gender. Once she wrote the words of a sutra on a piece of skin peeled or cut off from her hand,9 and on other occasions she poured oil into her palm and lit it while chanting sutras, perhaps as part of an ordination practice. Such extreme acts are not unknown in Buddhism.10 Scholar Barbara Ruch has researched examples of self-mutilation carried out by religious women in Japan, who may have been striving to overcome human desires and render themselves genderless.11 Bunchi’s half-brother Shinkei (1649–1706), prince-abbot of Ichijōin temple in Nara, painted and inscribed a portrait of her in the year following her death. The painting powerfully conveys her fortitude and dedication to the Buddhist dharma (fig. 2). He did not attempt to idealize her but shows her wearing a simple bast-fiber black robe and brown kesa vestment draped over her left shoulder. Shinkei sums up her lifelong practice in one of the lines of the poem: “She trampled the great earth to dust and smashed the great void to oblivion.”12

In addition to calligraphy, Bunchi created paintings of important Buddhist figures (Daruma, Kannon), clay portrait sculptures, and small plaques with embroidered characters. She also made some unique myōgō using her emperor father’s fingernail clippings.13 Most of her works are religious in nature and done mainly for herself and the people or temples with which she was intimately connected. Nearly all remain at her convent, Enshōji, or are in other temple collections; the Fong-Johnstone scroll is a rare example that traveled outside Japan.

The burgeoning interest in Zen practice among Kyoto’s imperial family and court nobility may have sparked a similar interest in Bunchi’s younger contemporary, Ryōnen Gensō. Ryōnen’s mother was an attendant to Empress Tōfukumon’in (1607–1678), the daughter of Shogun Tokugawa Hidetada who married Emperor Gomizuno-o the year after Bunchi was born.14 As a youth, Ryōnen served Tōfukumon’in’s granddaughter Yoshi no Kimi, but by this time, Bunchi had already left the palace and was living at Enshōji in northeastern Kyoto. Emperor Gomizuno-o and Tōfukumon’in were both fervent pupils of Zen, and by 1650, the emperor was becoming a major patron of the newly introduced (from China) Rinzai Zen school that became known as Ōbaku. There was a kind of “Ōbaku boom,” and Ōbaku Zen temples were rapidly established throughout Japan. Ryōnen’s two brothers became Ōbaku priests, but at the age of seventeen, she was married to a Confucian scholar-doctor.15 Ten years later, she left her family and entered the Rinzai Zen imperial convent Hōkyōji, where she was tonsured by one of Emperor Gomizuno-o’s daughters, Richū (1641–1689).16

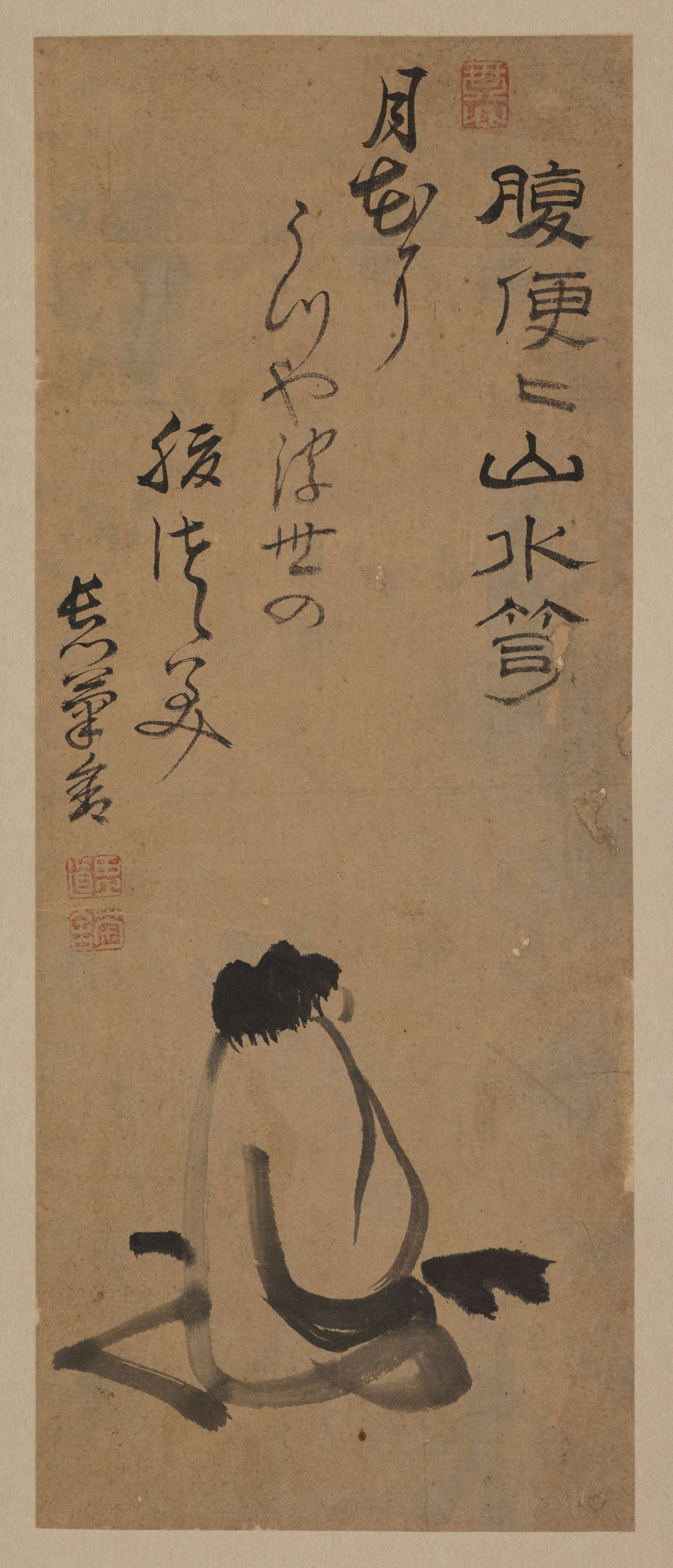

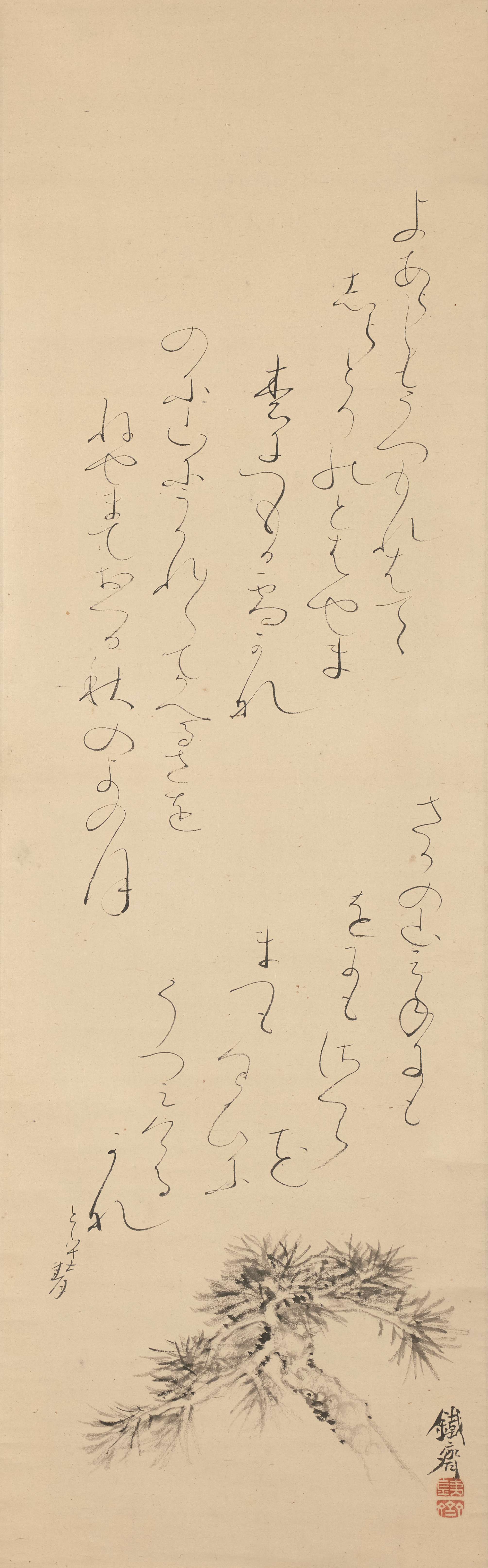

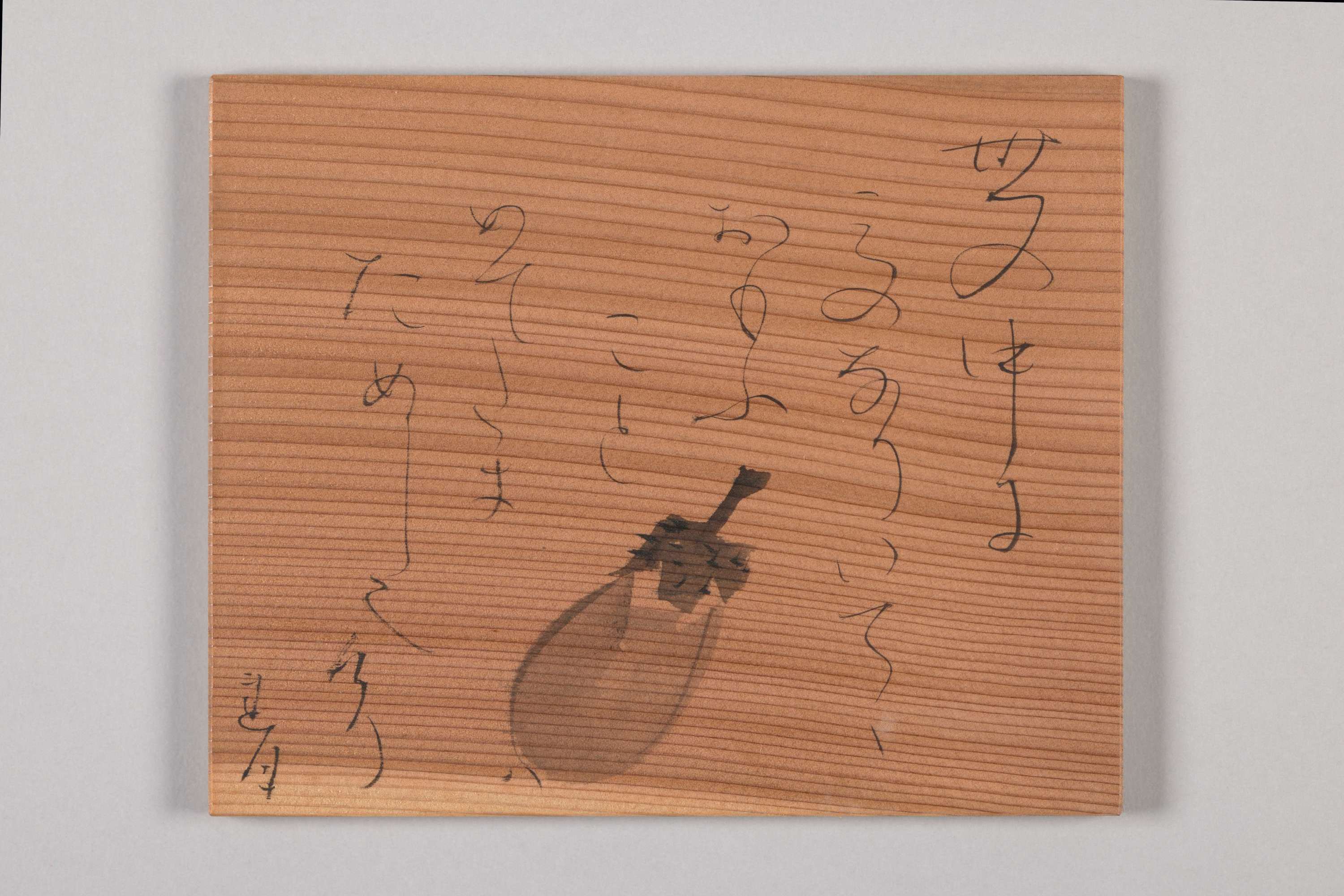

It is unclear how long Ryōnen resided at Hōkyōji, but she left to go to Edo (presumably with some sort of introduction), aspiring to study under Tetsugyū Dōki, disciple of the emigrant Chinese priest Mu’an (in Japanese, Mokuan). However, she was refused by him on the basis that her beauty would be a distraction to the monks in training. Ryōnen then went to see another disciple of Mu’an, Hakuō Dōtai, at the temple Daikyūan. She was again turned away, and since her beauty was an “obstruction,” she pressed a hot iron to her face to show her commitment and willingness to destroy her femininity in order to devote herself to Zen practice. Ryōnen was not the first woman to disfigure herself in this manner, as there are stories of earlier Japanese female clerics who similarly scarred their faces.17 To mark this act of religious determination, she composed the following two poems (a quatrain in Chinese and waka verse in Japanese) and presented them to Priest Hakuō. The second verse is the one that appears in the scroll in this exhibition (fig. 3).

Long ago I played games at court where we burned orchid incense;

now to enter the Zen path I burn the flesh of my face.

The four seasons flow naturally one season to another.

I don’t know who it is now in the midst of this change.

In this living world,

my flesh is burned and thrown away.

I would be wretched

if I did not think of it as kindling that burns away my sins.18

Impressed by her fervor, Hakuō accepted her as a disciple, and she trained under him for several years before he designated her as his dharma heir in 1680. Ryōnen later established her own temple, and the priest who had initially refused her, Tetsugyū, presided at the dedication of her Nyoirin Kannon Hall in 1694. Since the poem in the Fong-Johnstone collection is signed “Taiunji Ryōnen,” it must date from after her temple was officially designated as the Ōbaku Zen temple Taiunji in 1701.19 Ryōnen became famous for the radical act of scarring her face that inspired these poems, and the existence of numerous scrolls by her hand suggests that she received many requests for her potent verses.20 Like Bunchi, Ryōnen studied poetry and calligraphy from her childhood, and her manner of writing reflects the style prevailing at the court.

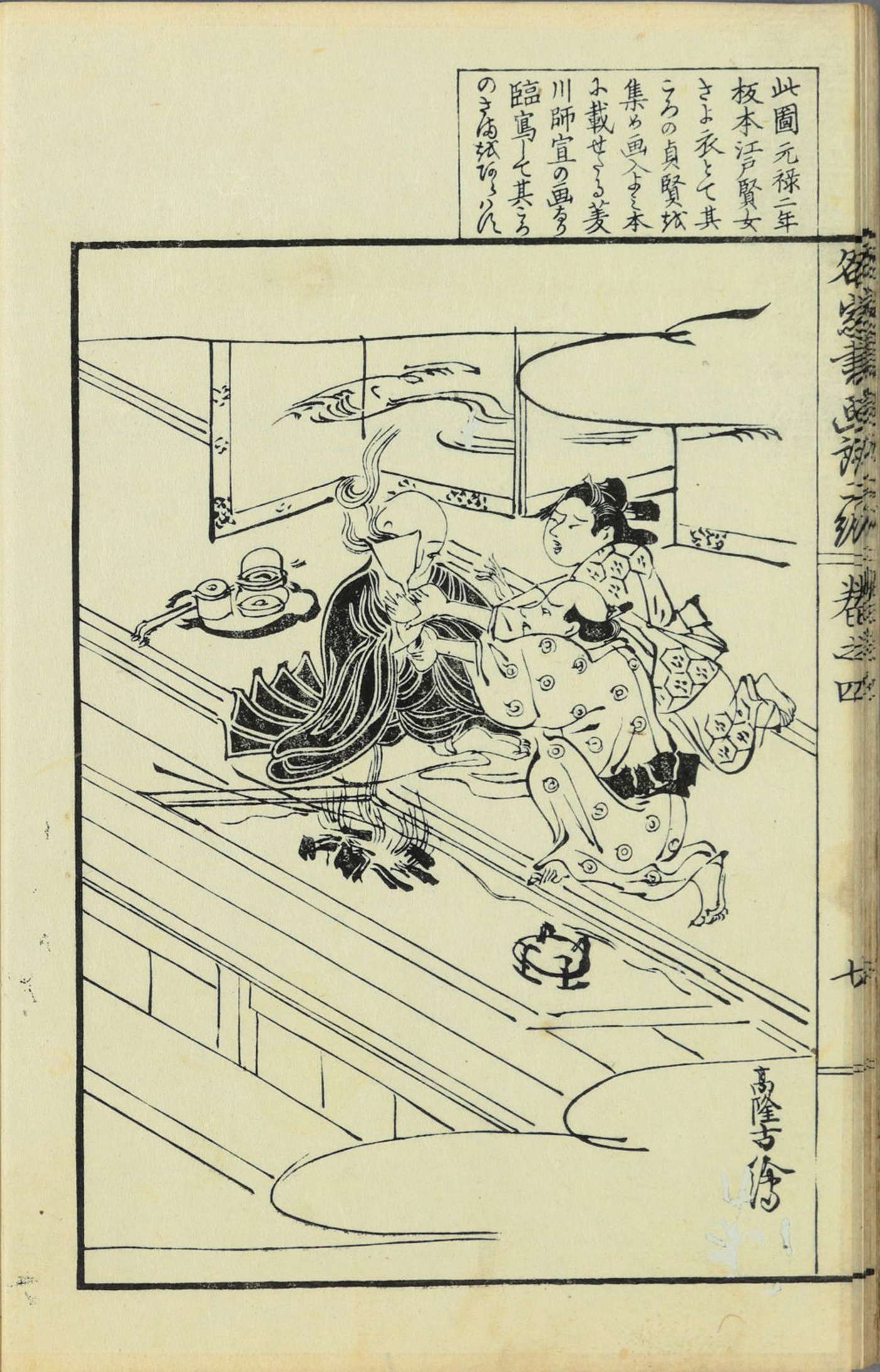

Ryōnen’s two verses, accompanied by illustrations of her burning her face (fig. 4), appeared in numerous woodblock-printed books and gazetteers, as well as ukiyo-e featuring famous women, such as the print by Utagawa Kunisada (Toyokuni III) (fig. 5). She first became known in the West through Lafcadio Hearn, who wrote a paper titled “The Nun Ryōnen: Fragments of a Japanese Biography,” which was read at the meeting of the Japan Society of London on April 13, 1904.21 Famous for his books on Japan recounting legends and ghost stories, he presented a fictionalized account of Ryōnen’s life, emphasizing her spirit of self-sacrifice.

Free-Spirited Poet Nuns: Kikusha and Rengetsu

Unlike the two nuns discussed above, Tagami Kikusha (田上菊舎 1753–1826) and Ōtagaki Rengetsu (太田垣蓮月 1791–1875) did not seek out rigorous religious instruction, nor did they strive to become leaders of temples. Rather, they took Pure Land Buddhist vows after being widowed, which was an accepted way to step away from family and social obligations. Their status as “nuns” gave them the freedom to move around as individuals; both women associated with other poets and painters and devoted themselves to composing poetry and creating art. Kikusha became renowned for her haikai and Rengetsu her waka. Both were incredibly prolific, and the vast numbers of extant works attest to their popularity during their lifetimes. They have both been the subject of numerous books and exhibitions,22 and the growing number of English publications is spurring on their global recognition as poets.23 Moreover, organizations and websites have been established to make their poetry available to a wide audience.24

Born in the small village of Tasuki in the province of Nagato (present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture),25 Kikusha began to seriously study and compose haikai after her husband’s untimely death (she became a widow at the age of twenty-four). Childless, she returned to her parents' home and adopted the name Kikusha (1778). At the age of twenty-nine (1781), after taking the tonsure at the Shin sect Buddhist temple Seikōji in Hagi (Yamaguchi Prefecture), she embarked on the first of what became a lifelong series of journeys throughout Japan. Kikusha had an unquenchable curiosity about the world and a burning desire to meet and interact with other cultural figures and poets. Similar to the famous poet Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694), for whom traveling was a kind of spiritual pursuit, her journeys provided opportunities for self-discovery and refining her literary skills, and she is sometimes referred to as a “Female Bashō.” Kikusha traveled all over Japan’s main island of Honshu as well as Kyushu; along the way she spent three years in Edo.

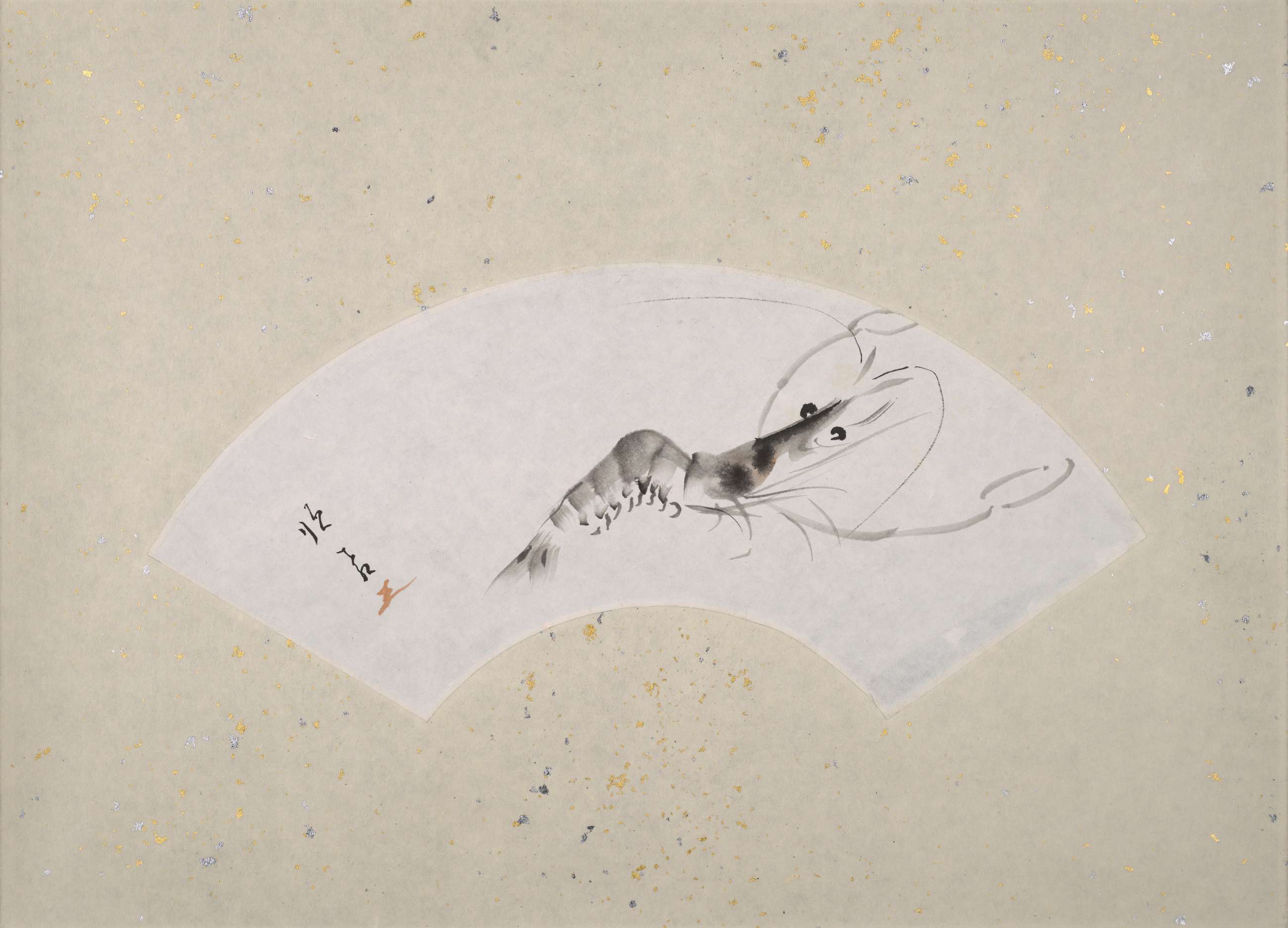

In addition to composing haikai, Kikusha mastered the fundamentals of ink painting and would frequently record her impressions in simple poem-paintings. She also became interested in Chinese literati culture and, befriending Japanese Confucian scholars and Ōbaku Zen priests, she learned how to compose Chinese poetry (kanshi) and to play the Chinese zither (in Japanese, shichigenkin). Kikusha did numerous paintings of herself with cropped hair typical of lay nuns, seated in front of her zither.26 She inscribed the self-portrait in the exhibition (fig. 6) with six Chinese characters meaning “Satiated with Nature,” followed by the haikai poem below:

Moon and flowers

fill this world—

I beat my barrel belly.27

Although she probably received some basic instruction, Kikusha could be described as an amateur painter. Her paintings—always accompanied by poems—comprise a wide range of subjects, including landscapes, flowers and plants, figures, and animals. She was content with creating abbreviated, almost sketch-like works, which suited the brevity of haikai, and her paintings display the same carefree brushwork typical of other Edo period haikai poets. Kikusha’s fame led to many requests for her poem-paintings, which served as a source of her livelihood. The sale of her work is documented in letters from Kikusha to the priest of Senjūji temple in her hometown, who acted as an intermediary, fielding requests and handling transactions.

Kikusha kept diaries recording the places she visited, the people she met, and her own poems as well as the verses of others. Because of these travel records, we have a reasonably accurate outline of her life and the people she met. Her adventurous spirit, boundless energy, and insatiable desire to capture her impressions of the world with brush and ink were extraordinary for a woman of her day. As is true of many of the nuns included here, Kikusha expressed her strong will in her bold and dynamic brushwork.

Rengetsu was born into an entirely different world than Kikusha; instead of the countryside, she grew up in the old cultural capital of Kyoto. The origins of her birth parents are unclear, but she was adopted by the Ōtagaki family, whose head came to hold a high-ranking administrative post at the Pure Land Buddhist temple Chion’in in Kyoto.28 In her youth, she worked as a lady-in-waiting in the women’s quarters at Kameoka Castle in the outskirts of Kyoto.29 It was there that Rengetsu (her childhood name was Nobu) learned the classical waka poetry and calligraphy that became the foundation for her livelihood.

Rengetsu was married at the age of seventeen and bore three children, all of whom died. After separating from her husband, she remarried and had another child, but lost both her second husband and daughter to illness. At the age of thirty-three, she took the tonsure, adopting Rengetsu (literally, “lotus moon”) as her Buddhist name. She took up residence in a subtemple at Chion’in with her adoptive father (who also took vows), and they lived together until his death. Rengetsu then moved to the Okazaki district in eastern Kyoto, where many poets and artists lived. She studied waka with Kagawa Kageki and Mutobe Yoshika and within a few years had established a reputation as a poet. Her name was also included in such compendiums as the Heian jinbutsu shi (Record of Heian [Kyoto] Notables),30 and two volumes of her waka were published during her lifetime.31 Waka had been the prevailing form of literary expression for aristocratic women from ancient times, and by the Edo period (1615–1868) women from all walks of life were becoming literate and interested in composing poetry. Rengetsu and Kikusha had the advantage over counterparts from earlier periods of growing up in an age when many famous waka and haikai poets readily accepted and encouraged female pupils.

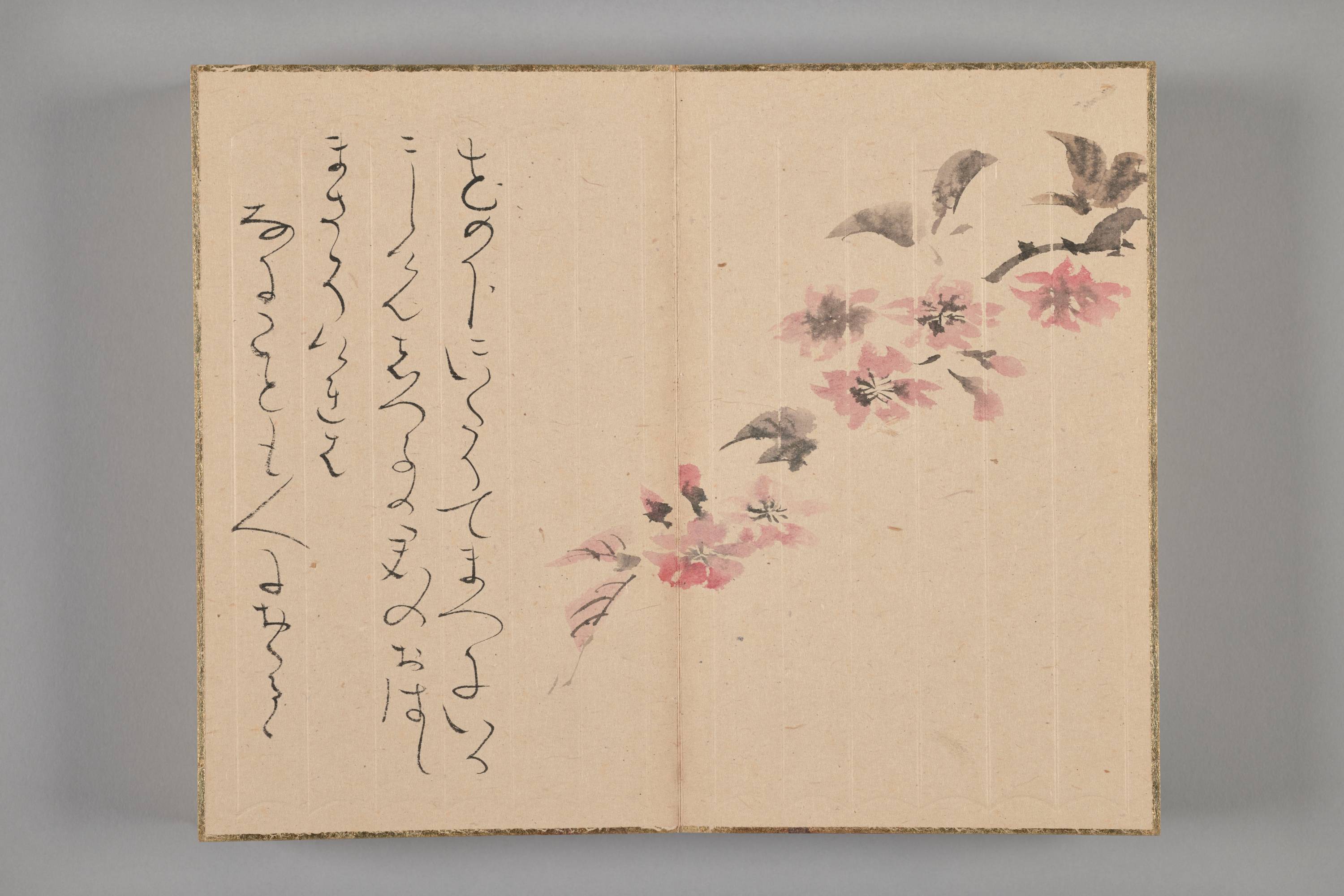

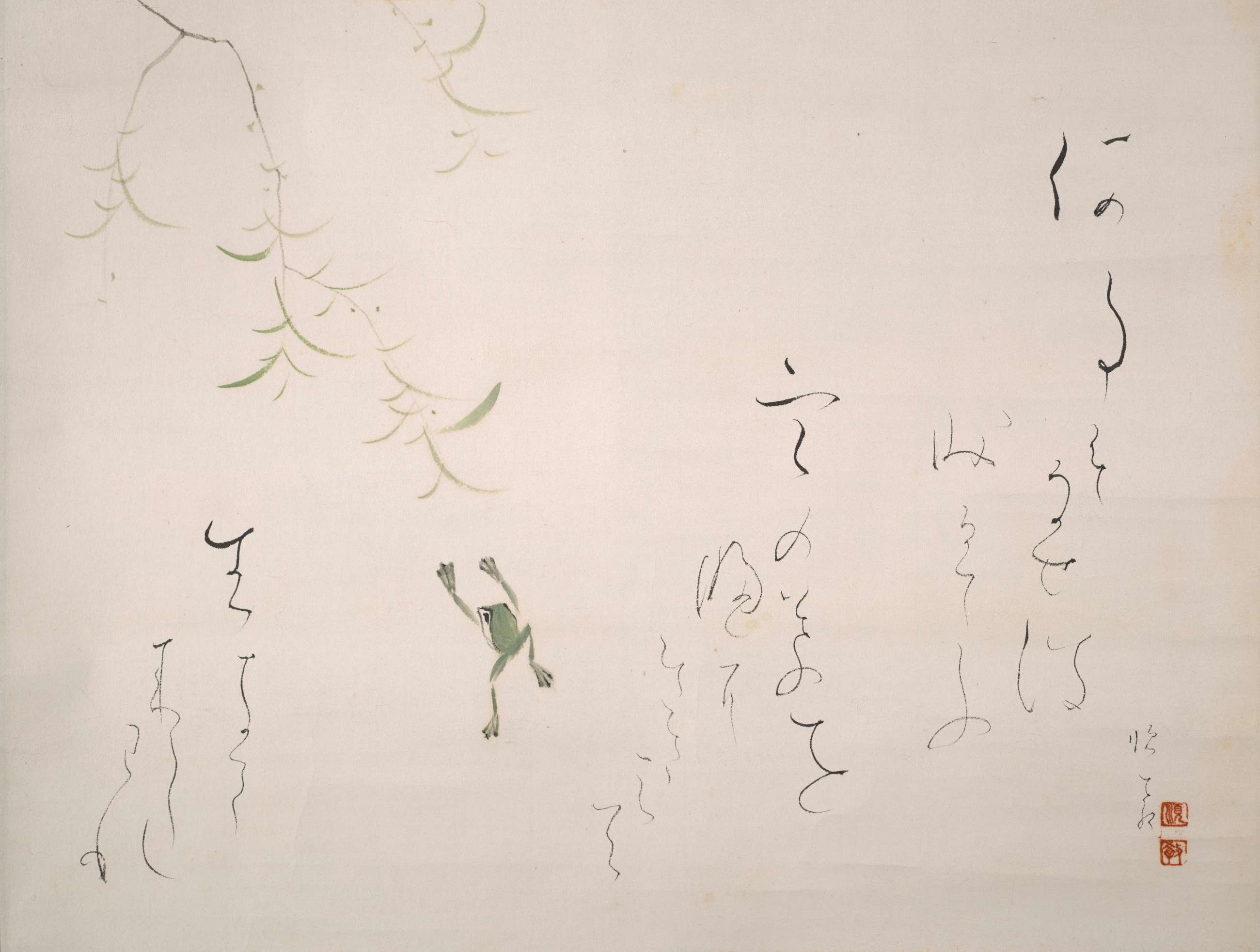

Like Kikusha, in addition to writing out her poems, Rengetsu also created poem-paintings, combining her waka with simply brushed seasonal motifs such as a branch of cherry or plum blossoms, the moon (fig. 7), eggplants (fig. 8), birds, butterflies (fig. 9), and occasionally animals. The subject matter is not so different from that of Kikusha, but their brush styles are at opposite poles: Kikusha’s coarse and dynamic, Rengetsu’s delicate and ethereal. Living in Kyoto, Rengetsu was no doubt influenced by the lyrical Maruyama-Shijō tradition of painting, which emphasized nature subjects modeled with soft ink and color washes. She associated with many painters and sometimes inscribed her poems on their paintings. Examples of “joint creations” (gassaku) in the exhibition include those done with Tomioka Tessai (富岡鉄斎 1836–1924) and Wada Gesshin (和田月心/ 1800–1870) (figs. 10 and 11). Rengetsu’s unique calligraphic style, featuring elegantly brushed, threadlike lines, is easily identifiable and, judging from the scores of extant works, was highly admired and sought after. She herself loved to write, as expressed in the following verse:

Taking up the brush

just for the joy of it,

writing on and on, leaving behind

long lines of dancing letters. 32

Midpoint in her career, Rengetsu began creating simple ceramic wares on which she either inscribed (with a brush) or incised (with a sharp tool) her poems. She was not the first to write verses on pottery. Half a century earlier, Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743) was producing a wide range of ceramic wares in Kyoto, including some inscribed with Chinese poems, and the literati (bunjin) artist Aoki Mokubei (1767–1833) also occasionally inscribed verses on his pottery. Rengetsu crafted most of her vessels by hand rather than by using a wheel and had them fired at kilns in eastern Kyoto. She also cooperated with professional potters, who created the wares and then either had Rengetsu add her waka or inscribed the verses themselves.33 For example, the inscription on the box for two tea bowls (fig. 12) records that it is by the potter Kuroda Kōryō (1823–1895), who added Rengetsu’s waka. “Rengetsu ware,” with its sublime synthesis of poetry, calligraphy, and pottery, proved immensely popular, which led to imitations, making connoisseurship of her pottery a very thorny issue.34 Excavations reveal that her wares were used by people from all walks of life and were even purchased as a kind of Kyoto “souvenir” and taken to Edo.35

The range of Rengetsu’s ceramics is well represented in the exhibition: sencha teaware, sake vessels, small plates, incense jars, and flower vases. The lotus leaf figures prominently in Rengetsu’s work; it was certainly appropriate because of its symbolism in Buddhism and connection to her name.36 The success of her pottery was linked to her eminence as a poet and her exquisite calligraphy, which gave owners the added pleasure of savoring her waka as well as the drink or food served in the vessels. Sayumi Takahashi has done some interesting research regarding the relationship between the content of Rengetsu’s waka and the containers on which the words are written.37

Some scholars believe that her mature calligraphy style, displaying slender lines with only subtle variations in thickness, was influenced by the incising of her poems into pottery. For example, Rengetsu often chose to use kana script instead of Chinese characters because the simpler syllabary characters were easier to incise and created less excess clay that had to be cleaned away. In order to make her poems easier to incise (and read), she wrote kana forms individually, leaving generous amounts of space around the lines; it is rare to find her linking more than two or three characters together.

Whereas Kikusha moved around Japan as she wished, Rengetsu reportedly changed her residence in Kyoto dozens of times to escape from people seeking to meet her and acquire her work. The fact that she was a Buddhist nun added to her celebrity status. Like Kikusha, she was not a full-fledged nun, but the verses of both female poets often embody Buddhist teachings.

Yoshi-ashi ni

watari yukuyo ya

muichimotsu

On a reed

traversing this transient world,

not one single thing.—Kikusha38

Clad in black robes,

I should have no attractions to

the shapes and scents of this world;

But how can I keep my vows

gazing at today’s crimson maple leaves?—Rengetsu39

Perfectly aware,

not a thought,

just the moon

piercing me with light

as I gaze upon it.—Rengetsu40

Although she took her original vows at a Pure Land temple, Rengetsu associated with clergy from various sects. In her later years, she moved into a small hut on the grounds of Jinkōin temple northwest of Kyoto at the invitation of the chief priest, Wada Gesshin (also known as Gōzan, 1800–1870). It was here that she lived out the remainder of her life. She was such a celebrated figure in Kyoto that numerous artists did portraits of her. The example in the exhibition by Suganuma Ōhō showing Rengetsu seated in her hut, writing poems on pottery (fig. 13), was probably inspired by Tessai’s famous portrait of the wizened old nun in the collection of Jinkōin.

Unconventional Nuns and Their Idiosyncratic Calligraphy: Junkyō and Myōdō

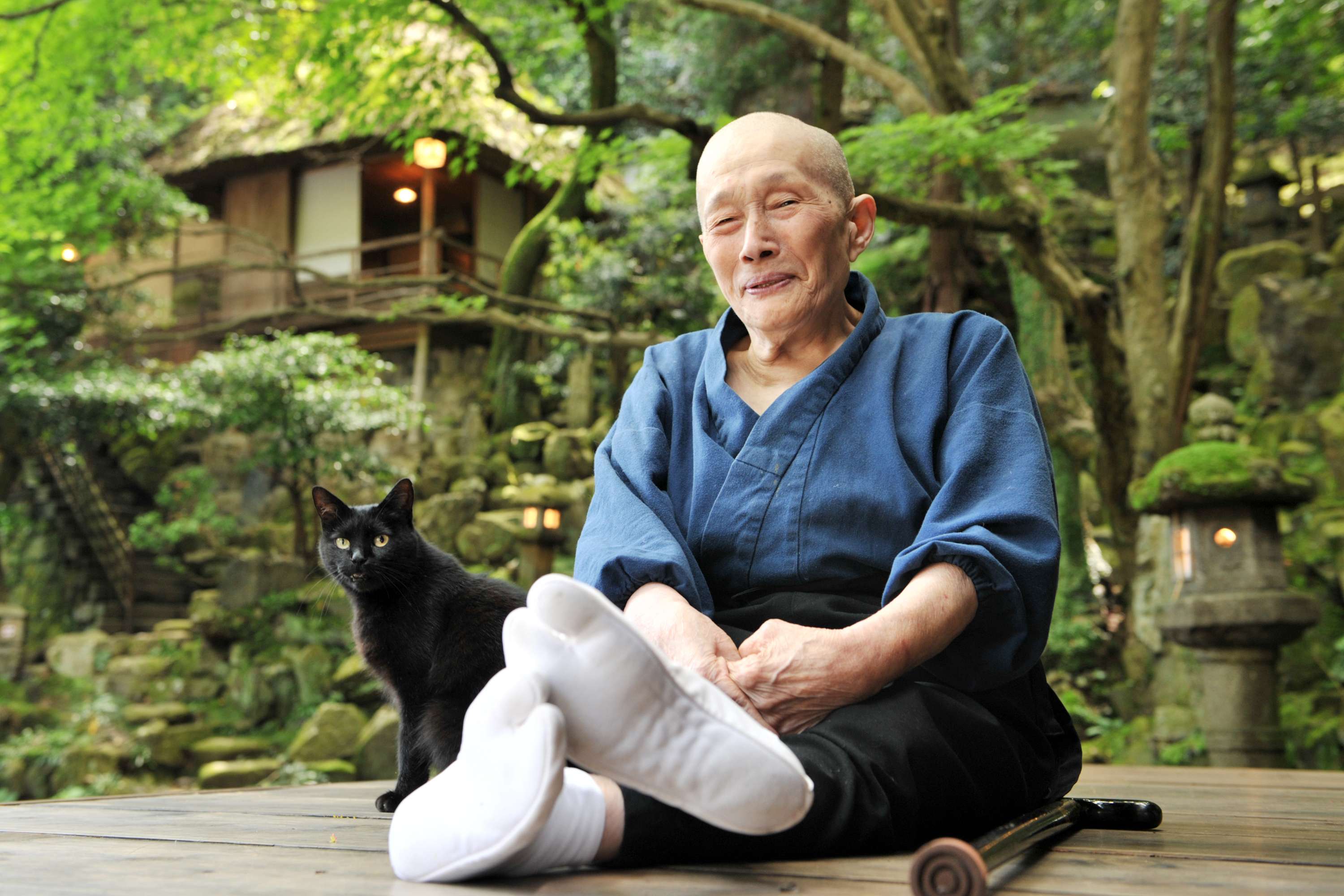

People are immediately captivated when they see the calligraphy and hear stories about Ōishi Junkyō (大石順教 1888–1968) and Murase Myōdō (村瀬明道 1924–2013). Since both women lived into the modern age, tales of personal encounters with them abound. After taking the tonsure, both women eventually settled into small temples on the outskirts of Kyoto. They took up the brush on a regular basis, leaving a large body of work. Their calligraphic styles are dramatically different, reflecting the life circumstances and personalities of the two nuns, one a dancer turned social worker and the other specializing in vegetarian Buddhist cuisine. Both women authored books that include biographical material as well as discussions of their livelihood, and they were the subjects of television and film documentaries.41

My first introduction to Junkyō’s calligraphy was in an art dealer’s shop in Kyoto, where I was shown a tanzaku poem card on which she had written a waka with gold ink. The writing itself was beautiful, but what amazed me most was hearing that she had done it by holding the brush in her mouth, having lost her arms. I then learned the gruesome details of how she had begun a promising career as a geigi dancer in Osaka, but one night, her adoptive father (who was also the proprietor of the teahouse where she lived) came home drunk and, brandishing a sword, killed six of the residents. Junkyō (her childhood name was Yone, geigi name Tsumakichi) survived the attack, but both of her arms were severed. She was seventeen at the time. After recovering from her injuries, she worked for a while in a traveling theatrical group, singing ballads, dancing, and doing comical storytelling. But she found life as a, in her words, “spectacle” unfulfilling, and one day, after watching a canary feed its chicks with its beak, she was inspired to try to write by holding a brush in her mouth. She retired from the stage shortly thereafter and devoted herself to the study of painting and poetry.42 Since she had never gone to school, Junkyō was illiterate, but she now became an avid student of literature.

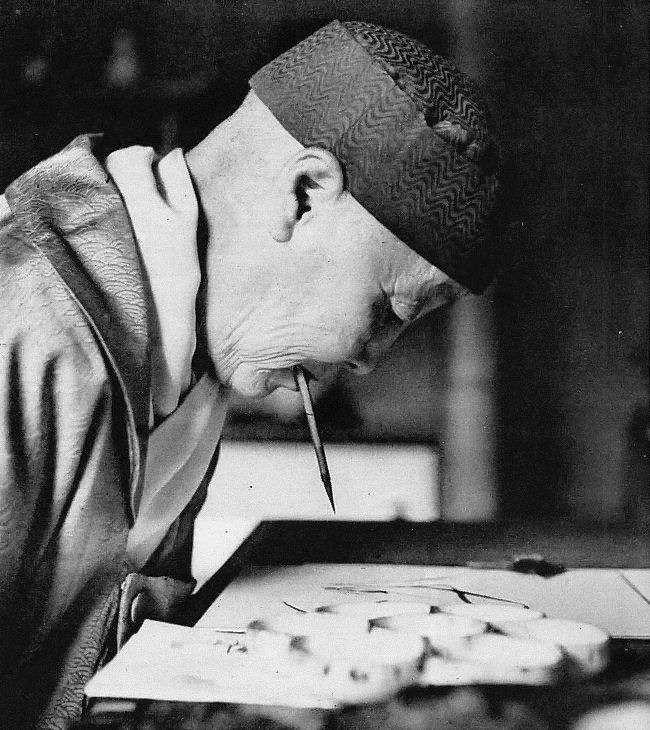

Junkyō married the calligrapher-painter Yamaguchi Sōhei in 1912 and had two children, but after fifteen years they divorced. She supported herself and her children through painting and calligraphy and set up a counseling service for people with disabilities. While she had often sought spiritual solace at temples, in 1933 (at age forty-five) she officially took the tonsure at Kongobūji on Mt. Kōya, adopting the Buddhist name Junkyō. Three years later she moved into the Shingon temple Kanshūji in Yamashina, east of Kyoto, where she continued to counsel and empower people with disabilities, teaching about Buddhism. In 1947, she founded Bukkōin; she lived out her life at this small temple, and through her activities she served as a model. Not only could she write and paint by holding a brush in her mouth (fig. 14), but she raked her own garden and pulled out weeds with her toes. Her tenacity and independence have inspired others and even led to comparisons with Helen Keller, who actually met Junkyō during one of her trips to Japan.

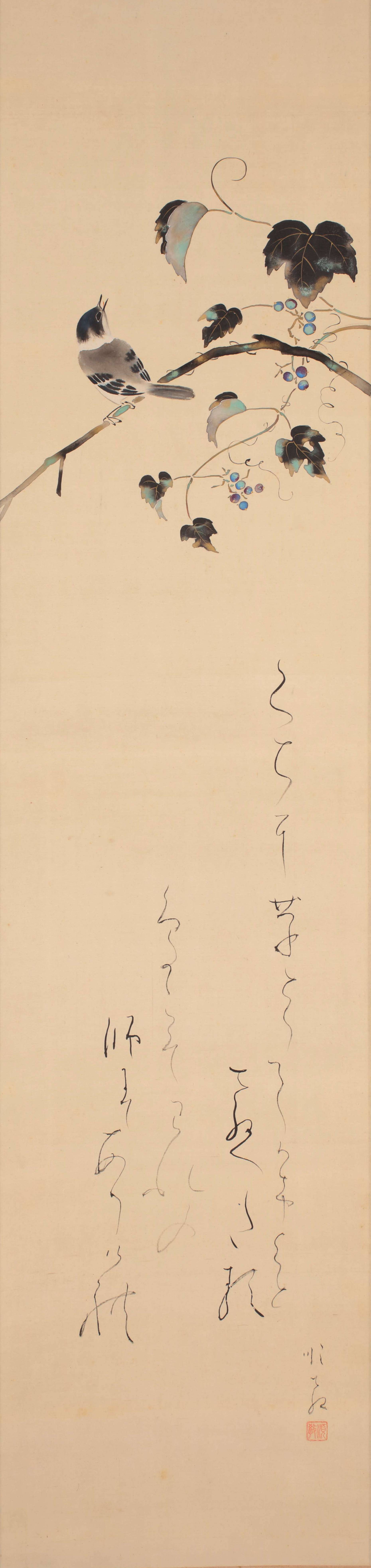

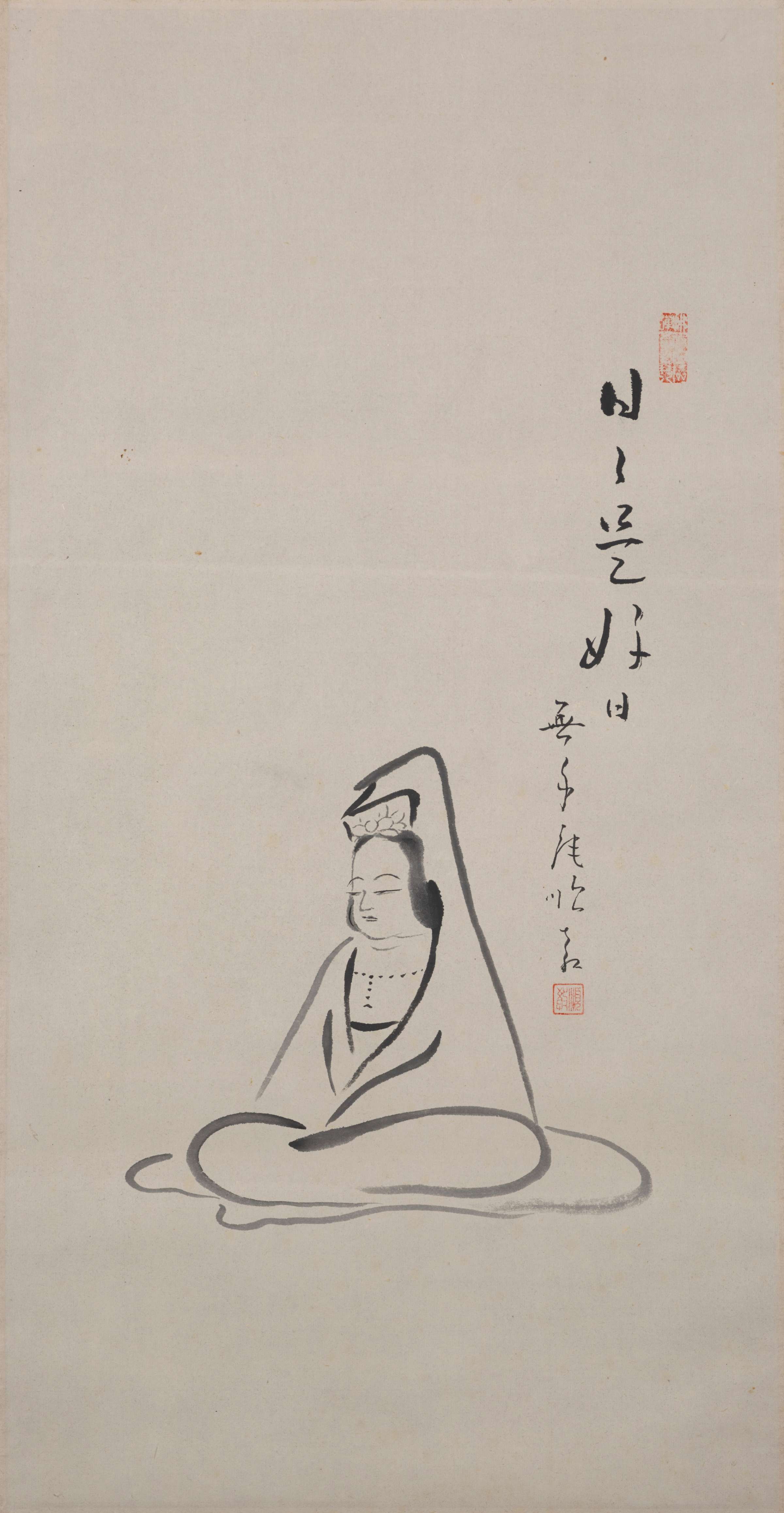

I was taken to Bukkōin by the art dealer who initially introduced me to her work and was able to meet her son and daughter-in-law, who showed me various works and photographs and also gave me some books and an unpublished manuscript that included excerpts from Junkyō’s diary. I was also given a newspaper clipping that mentioned an exhibition of her work at a museum in Munich in 1966. Nature subjects prevail in Junkyō’s oeuvre (figs. 15 and 16), but she also depicted the bodhisattva Kannon (fig. 17) and occasionally other figures. She frequently added the Buddhist maxim “Every day is a good day” to her Kannon paintings; this example is signed “Handless Junkyō.” The paintings in the Denver Art Museum exhibition, Her Brush: Japanese Women Artists from the Fong-Johnstone Collection, are rather simply brushed, but other works by Junkyō are surprisingly detailed and colorful and must have taken her a long time to complete. An example is her lovely rendering of birds and grapes inscribed with the poem about being inspired by the canary quoted above (fig. 18). The simplicity of her writing shares some qualities with Rengetsu’s. In fact, Junkyō was very much aware of Rengetsu’s poetry and calligraphy and reportedly studied her script in her thirties and forties.43 She did paintings of a woman fulling cloth on which she inscribed a waka by Rengetsu, whom she acknowledges in her inscriptions.44 While Junkyō’s calligraphy does not display the hair-fine brushlines of Rengetsu’s, and the rhythmic flow is different, aesthetically the similarities are there, especially because both nuns wrote primarily with the simplified kana script.

People who met Junkyō described her as “radiant,” “humble,” and “peaceful”; these same qualities emanate from her paintings and calligraphy. In a letter to friends shortly before her death, she wrote that she had suffered much bitterness because her arms were cut off but that the incident enabled her to find the path of Buddha and inner peace. Getting to know others in the limb-loss community had been a special part of her life, and she wanted to thank everyone and tell them to keep up their spirits.45

The Zen nun Murase Myōdō also shared a similar path; in 1963, at the age of thirty-nine, she was hit by a car while out shopping, leaving her partially paralyzed. She lost the use of her right, dominant arm. She then threw herself wholeheartedly into using her left, preparing vegetarian Buddhist cuisine called shojin ryori, as well as creating bold, dynamic calligraphy.

Born into the family of a rice merchant in Aichi Prefecture (she was the fifth of nine children), at the age of nine Myōdō entered the Rinzai Zen temple Kōgenji in Kyoto. Her decision was influenced in part by the traditional belief that if one child took the tonsure, other members of the family could be reborn in paradise. At age fourteen, she went to a special school for nuns in Gifu and then continued five more years of training at the Rinzai Zen convent Tenneiji. She returned to Kōgenji in 1943 and did further training at Enkōji convent in Kyoto, then served at two other temples before becoming head of Gesshinji in Ōtsu city, Shiga Prefecture, in 1975. There Myōdō became famous for her vegetarian cuisine, prepared with the deep mindfulness characteristic of Zen discipline. She claimed that while pouring her heart and soul into preparing food, she always kept foremost in mind the people who would eat it. Her goal was to nurture by providing them with something healthy and delicious.

After the car accident, Myōdō was hospitalized for nine months. She suffered severe pain and found it difficult to breathe, but she remembers being encouraged by a doctor who said, “If the Buddha hadn’t wanted you to live, you’d be dead. The fact that you are alive is because you are needed.”46 Hearing that gave her strength and renewed her sense of purpose in life. She was determined to live every day fully, and cooking and preparing food became her spiritual practice. Having lost the use of her right arm and right leg, she trained herself to use her left hand to hold a writing brush, as well as to chop vegetables and grind sesame seeds with pestle and mortar for what became one of her specialties, sesame tofu. Giving by cooking and providing people with a pleasurable dining experience became her passion.

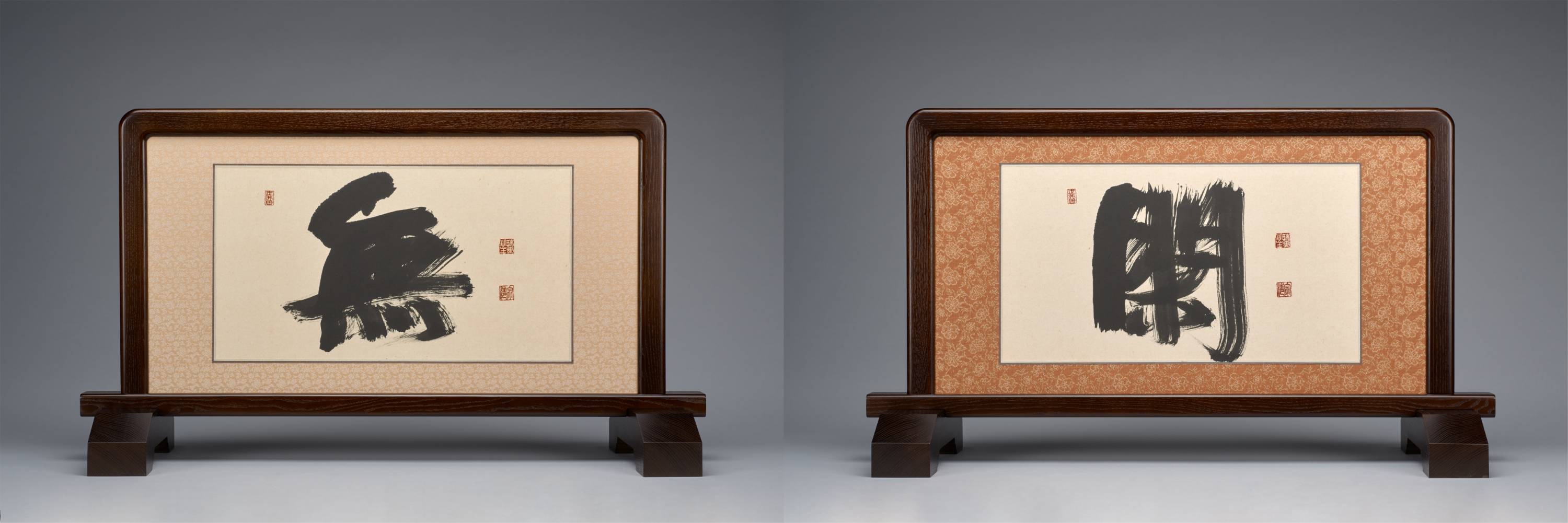

Regretfully, I never had the chance to meet Myōdō or enjoy her shōjin ryōri at Gesshinji. I first learned about this remarkable nun through seeing some examples of her boldly brushed calligraphy in a charity exhibition of works by contemporary Zen priests in 1997. Her personality, captured in a photograph for the cover of her 2004 book (fig. 19), was the opposite of Junkyō’s: brash, outspoken, with a wry sense of humor. This is reflected in her brushwork, exemplified in the hanging scroll Breaking Waves in the Pines (shōtō) (fig. 20) and two-sided screen panel comprising the single characters “mu” and “kan” (fig. 21), which together mean “emptiness/quietude." Myōdō wrote that when she was young, at one point she imagined that she would like to live like Rengetsu, crafting clay pots and composing poetry, but after losing the use of her right arm and leg, she found it impossible. She then persevered, learning how to write calligraphy with her left hand.47 As she became famous for her cuisine, requests for her brushwork no doubt increased. The majority of Myōdō’s extant works were executed with a large brush, which was perhaps easier for her to handle. She once said that calligraphy and cooking are both like “fighting with a real sword” (shinken shōbu). “Facing a white sheet of paper, it is you who makes it [the calligraphy or the food] live or die.”48 Interviews (in Japanese) with Myōdō are easily accessible on YouTube. While she is no longer with us, we can still hear her deliver short sermons on “life” and also sense that vivid life in her brushwork.

-

Bunchi’s grandmother (Emperor Gomizuno-o’s mother) and Ryōnen’s mother were both from the Konoe family. ↩︎

-

See Patricia Fister, “Creating Devotional Art with Body Fragments: The Buddhist Nun Bunchi and Her Father, Emperor Gomizuno-o,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 27, nos. 3–4 (2000): 213–38; Fister, Art by Buddhist Nuns: Treasures from the Imperial Convents of Japan (New York: Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies, Columbia University, 2003), 22–3; Fister, “Visual Culture in Japan’s Imperial Buddhist Convents: The Making of Devotional Objects as Expressions of Faith and Practice,” in Zen and Material Culture, ed. Steven Heine and Pamela D. Winfield (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2017), 164–96; Patricia Fister, et al., Amamonzeki: A Hidden Heritage: Treasures of the Japanese Imperial Convents (Tokyo: Sankei Shimbun, 2009), 100, 288–90. ↩︎

-

This information is included in her written account of the founding of Enshōji, titled Fumonzan no ki (Record of Mt. Fumon), 1676. Fumon is the “mountain name” (sango) of Enshōji; literally meaning “universal gate” or “gate of Buddhist understanding,” it forms part of the title of the Kannon Sutra, “Kanzeon bosatsu fumonbon.” ↩︎

-

Kasuga Myōjin refers to a conglomerate of Shinto divinities at Kasuga, also called Kasuga Daimyōjin (Great Resplendent Kasuga Deity). There is a large shrine devoted to Kasuga Myōjin near Kōfukuji temple in Nara city, and branch shrines were also established throughout Japan. ↩︎

-

According to the Kasuga Gongen genki, Kasuga Myōjin was first referred to as a bodhisattva in an oracle dated 937 and is regarded as a manifestation of Shaka Nyorai. Royall Tyler, The Miracles of the Kasuga Deity (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990), 25, 103. ↩︎

-

There is also a Kasuga myōgō scroll at Enshōji. Suenaga Masao and Nishibori Ichizō, Bunchi jo-ō (Princess Bunchi) (Nara, Japan: Enshōji, 1955), 213. ↩︎

-

Fumonzan no ki. Collection of Enshōji. ↩︎

-

For a photograph of the shrine, see Fister, Art by Buddhist Nuns, 47. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 64–5. ↩︎

-

See James A. Benn, “Where Text Meets Flesh: Burning the Body as an Apocryphal Practice in Chinese Buddhism,” History of Religions 37, no. 4 (May 1998): 295–322; James Baskind, “Mortification Practices in the Ōbaku School,” in Essays on East Asian Religion and Culture, ed. Christian Wittern and Shi Lishan (Kyoto: Kyōto Daigaku Jinbun Kagaku Kenkyūjo, 2007), 149–76. ↩︎

-

Barbara Ruch, “Burning Iron against the Cheek: A Female Cleric’s Last Resort,” in Engendering Faith: Women and Buddhism in Premodern Japan, ed. Barbara Ruch (Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan, 2002), lxv–lxxvii. ↩︎

-

Translation by Norman Waddell. For the entire poem, see Fister, Amamonzeki: A Hidden Heritage, 100. ↩︎

-

Fister, “Creating Devotional Art with Body Fragments,” 216–20; Fister, Art by Buddhist Nuns, 54–5. ↩︎

-

Bunchi’s mother was Yotsutsuji Yotsuko (1589–1638), another wife of Emperor Gomizuno-o. Ryōnen’s father was Katsurayama Tamehisa. For more information about Ryōnen’s life in English, see Fister, Art by Buddhist Nuns, 26–7; Ruch, “Burning Iron against the Cheek.” ↩︎

-

Matsuda Bansui (1630–1703). The match was reportedly arranged by Yoshi no Kimi’s brother, Konoe Iehiro (1667–1736). Accounts differ, but they seem to have had two to four children. ↩︎

-

Ryōnen’s brother Daizui Dōki (1652–1717), who studied under the Chinese Ōbaku priest Gaoquan (in Japanese, Kōsen), taught the imperial princess, who entered Hōkyōji ten to fifteen years after Ryōnen and eventually succeeded Richū as abbess. ↩︎

-

Two examples are the Rinzai nun Mugai Nyodai (1223–1298) and the Sōtō nun Eshun (active in the 1300s). ↩︎

-

Translations of both poems are by Barbara Ruch in Fister, Art by Buddhist Nuns, 81. The characters for the poem are:

生る世に 捨て焼く身や うからまし つみのたきぎと おもハざりせバ

Ikeru yo ni / sutete yaku mi ya / ukaramashi / tsumi no takigi to / omowazariseba ↩︎

-

Ryōnen’s temple Taiunji has not survived, and the artifacts were scattered. ↩︎

-

I know of four examples: one is preserved at Manpukuji and the others in private collections in Japan and the United States. For illustrations, see Patricia Fister, “Sannin no kinsei nisō to Ōbaku” [Three Edo-period Nuns and Ōbaku], Ōbaku bunka 118 (1999): 90; Fister, Art by Buddhist Nuns, 80–1. ↩︎

-

Published in Transactions and Proceedings of the Japan Society, London 6, no. 3 (1904): 374–88. Reprinted as a book in 1906. ↩︎

-

Tagami Kikusha: Kinsei joryū bunjin no sekai (Shimonoseki Shiritsu Chōfu Hakubutsukan, 1995); Un’yū to ama: Tagami Kikusha (Yamaguchi Prefectural Museum, 2003); Black Robe, White Mist: Art of the Japanese Buddhist Nun Rengetsu (Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2007); Ōtagaki Rengetsu: Poetry and Artwork from a Rustic Hut (Kyoto: Nomura Art Museum, 2014); Michifumi Isoda, Unsung Heroes of Old Japan (Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture, 2017). ↩︎

-

Verses are included in the following books: Makoto Ueda, ed., Far Beyond the Field: Haiku by Japanese Women (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003); Hiroaki Sato, ed. and trans., Japanese Women Poets: An Anthology (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2008); John Stevens, trans., Lotus Moon: The Poetry of the Buddhist Nun Rengetsu (New York: Weatherhill, 1994); Ōtagaki Rengetsu: Poetry and Artwork from a Rustic Hut (Kyoto: Amembo Press, 2014). ↩︎

-

The Kikusha Commemoration Society (Kikusha Kenshōkai), headed by Oka Masako (the eleventh-generation poet in Kikusha’s lineage), organizes events such as trips to places Kikusha visited and also supports publications of her poetry (www.kikusha.com). The society also publishes a journal, Kikusha kenkyū nōto, with articles related to Kikusha. The Rengetsu Foundation, based in Kyoto, has created an English website with a database of her poems (in both English and Japanese) and a digital archive of some of her work (www.rengetsu.org). ↩︎

-

For more details on Kikusha’s life in English, see Fumiko Yamamoto, “Chiyo and Kikusha: Two Haiku Poets,” in Fister, Japanese Women Artists, 1600–1900, 55–68; Fister, Kinsei no josei gaka-tachi; and Rebecca Corbett, “Crafting Identity as a Tea Practitioner in Early Modern Japan: Ōtagaki Rengetsu and Tagami Kikusha,” U.S.–Japan Women’s Journal 47 (2014): 3–27. ↩︎

-

Two examples are included in the catalog accompanying the 2003 exhibition at the Yamaguchi Prefectural Museum, Un’yū to ama: Tagami Kikusha. See Oka Masako, ed. Un’yū to ama: Tagami Kikusha. (Hōhokuchō, Japan: Kikusha Kenshōkai, 2003), plates 53 and 139. ↩︎

-

The characters for the title and poem are: 腹便々山水笥 月花に うつや浮世の 腹つづみ.

Tsuki hana ni / utsu ya ukiyo no / haratsuzumi ↩︎

-

I am grateful to Paul Berry for pointing this out to me. ↩︎

-

For further information in English on Rengetsu’s life, see Fister, Japanese Women Artists, 1600–1900, 144–46. ↩︎

-

Beginning in the year 1838. ↩︎

-

Rengetsu Shikibu nijo waka shū (1868) and Ama no karamu (1870). The former volume is a compilation of poems by both Rengetsu and her poetess friend Takebatake Shikibu (高畠式部 1785–1881), who is also represented in the Fong-Johnstone collection. ↩︎

-

Translation by John Stevens. Stevens, Lotus Moon, 108. ↩︎

-

These potters include Kuroda Kōryō (1823–1895), Tamaki Ryōsai (dates unknown), and Issō (dates unknown). ↩︎

-

Excavations of kiln sites in Kyoto confirm that “Rengetsu ware” (Rengetsu-yaki) by other potters was being produced during her lifetime. Several reports have been published by Chiba Yutaka from the Center for Cultural Heritage Studies, Kyoto University (formerly Center for Archaeological Operations). Chiba Yutaka, “Kōko shiryō to shite no Rengetsu-yaki,” The Annual Report of the Center for Archaeological Operations 2001 (2006): 311–26; “Rengetsu-yaki o mohōshita tōki ni tsuite: Kyoto Daigaku Byōin kōnai AE19-ku SK15 shutsudo shiryō,” The Annual Report of the Center for Cultural Heritage Studies 2016 (2018): 123–54. I am grateful to Richard Wilson, professor in the Department of Art and Archaeology at International Christian University, who informed me of the excavations many years ago and provided me with some of the data. ↩︎

-

Chiba Yutaka, “Kōko shiryō to shite no Rengetsu-yaki,” 322. ↩︎

-

Some scholars believe the lotus motif was developed for Rengetsu by Kuroda Kōryō. See Mitsuoka Tadanari, “Rengetsu-ni no tōgei,” in Koresawa Kyōzō et al., Rengetsu (Tokyo: Kōdansha, 1971). Karen Gerhart, who visited descendants of Kuroda living at Jōrakuji in Kyoto in March 1986, told me that they still possess molds with lotus designs believed to have been used by Kōryō. ↩︎

-

Sayumi Takahashi, “Beyond Our Grasp? Materiality, Meta-genre and Meaning in the Po(e)ttery of Rengetsu-ni,” Proceedings of the Association for Japanese Literary Studies 5 (Summer 2004): 261–78. ↩︎

-

Yoshi-ashi has the double meaning of “reed” and “good and/or bad (evil).” Kikusha undoubtedly had both meanings in mind when she composed this poem, which appears on a simply brushed picture of Bodhidharma. Poem translated by author. ↩︎

-

Translation by John Stevens. Stevens, Lotus Moon, 68. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 77. ↩︎

-

Books by Ōishi Junkyō: Horie monogatari: Tsumakichi jijoden (1930), Mute no shiawase (1949; multiple reprintings); Tana kokoro (1952), and Kokoro no te (1961). A television drama based on her life, “Namida hanagasanaide kudasai: Ōishi Junkyō-ni no shogai” (Please don’t shed tears: the life of nun Ōishi Junkyō) aired in 1981, and there is also a documentary produced in 2011 titled “Ten kara mireba” (Looking from heaven).

Books by Murase Myōdō: Gesshinji no ryōri (1983); Aru chisana zendera no kokoro michiru ryōri no hanashi (2003); Honmamonde ikinahare: “Gomadōfu tenkaichi” no anjusan ichidaiki (2004/2009); and “Akanjin” nande zettai inai (2008). Television specials include Shinshin komoru amadera no ryōri (March 17, 1988), Kokoro no jidai (July 3, 2005), and Seikatsu hotto mōningu: Kono hito ni tokimeki! (November 21, 2008). Myōdō also served as the model for the heroine of the serial morning television series Honmamon, which aired from October 2001 to March 2002. ↩︎

-

She studied painting with Wakabayashi Shōkei and poetry with the priest Fujimura Eiun, from Jimyōin in Osaka. ↩︎

-

Conversation with Junkyō’s son and his wife at Bukkōin, July 1986. I was also shown some examples of poems written on tanzaku by Junkyō that did indeed recall Rengetsu’s style. ↩︎

-

Before her signature, Junkyō wrote, “In admiration of (or honoring) Rengetsu.” For a photograph of one example, see Ōishi Junkyō-ni Itoku Kenshōkai, ed., Ōishi Junkyō-ni isakushū (Tokyo: Shunshūsha, 1984), plate 6. Fulling is a technique of pounding washed clothes to smooth out wrinkles (like ironing) and also brings out the glossiness and softness of the fabric. ↩︎

-

This letter is in the collection of Bukkōin. ↩︎

-

Murase Myōdō, Honmamonde ikinahare: “Gomadōfu tenkaichi” no anjusan ichidaiki (Tokyo: Bungei Shunshū, 2009), 20. ↩︎

-

Murase Myōdō, Gesshinji no ryōri (Tokyo: Bunka Shuppan Kyoku, 1983), 233. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 156. ↩︎

| words