Unstoppable (No Barriers)

Each of the works in this section addresses the subject of perseverance, overcoming personal and societal obstacles, and shattering the glass ceiling.

These artists dared to leave their enduring mark through art.

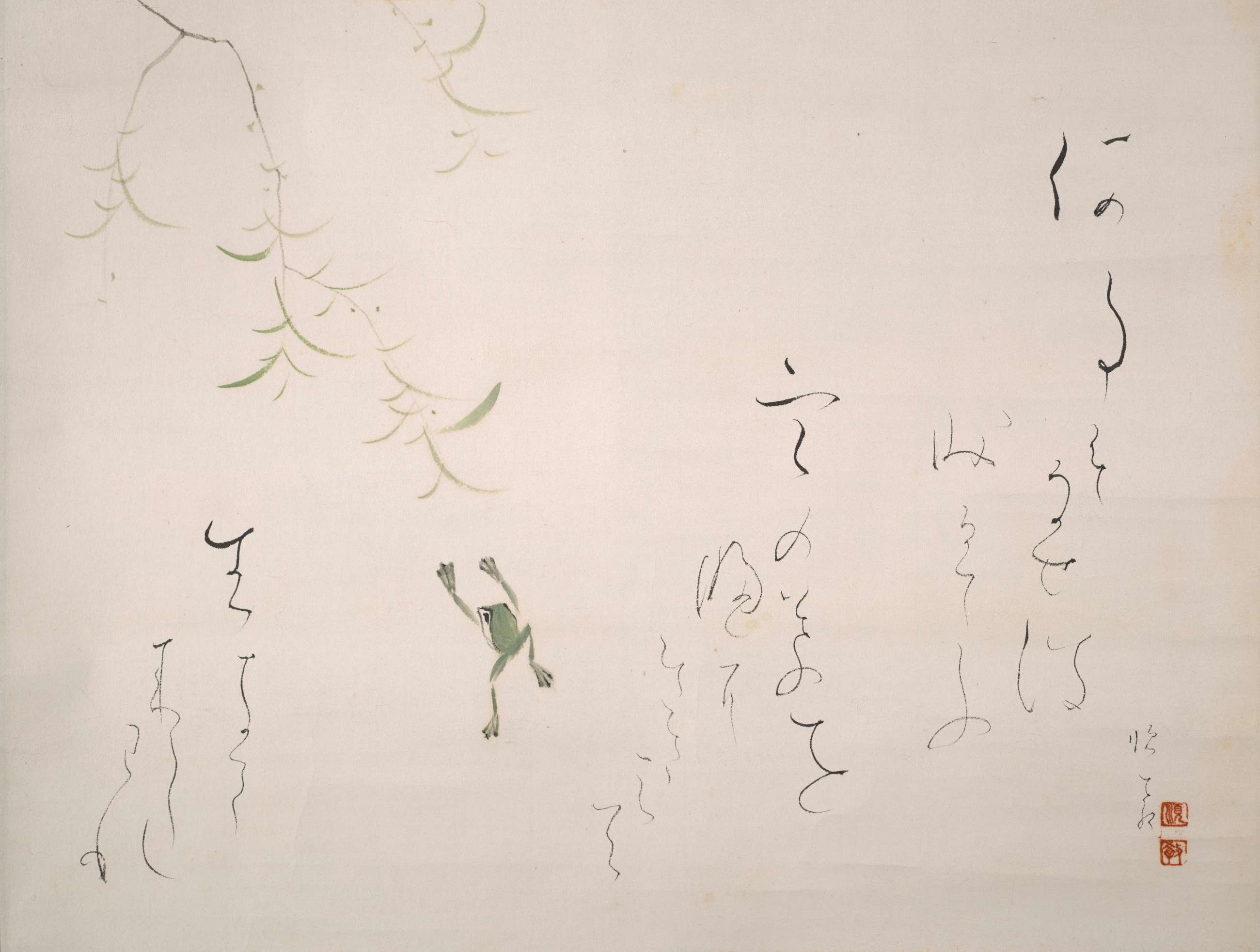

In this painting, Ōishi Junkyō borrows an anecdote from the life of the courtier Ono no Tofu (894–964) to express resilience and tenacity. Having failed to get a promotion seven times, the courtier was all but ready to quit. Dejected, he noticed a frog trying to reach a willow branch. Seven times, the frog leapt and failed. But then, mustering its strength, it jumped again—finally reaching the branch. Inspired, he persevered and on that eighth time succeeded, ultimately becoming an important statesman.

Petal by petal, this blossoming cluster of chrysanthemums unfolds against a subtle ink wash on plain silk. In lyrical gradations, the monochromatic ink merges with the dabs of green and pools at the edges of the leaves, vesting them with grace and beauty.

Little is known of Yamamoto Shōtō’s background, but her enduring mark survives though her own art and her legacy: her children followed her path, and her granddaughter, Yamamoto Suiun (active 1800s), became an accomplished painter.

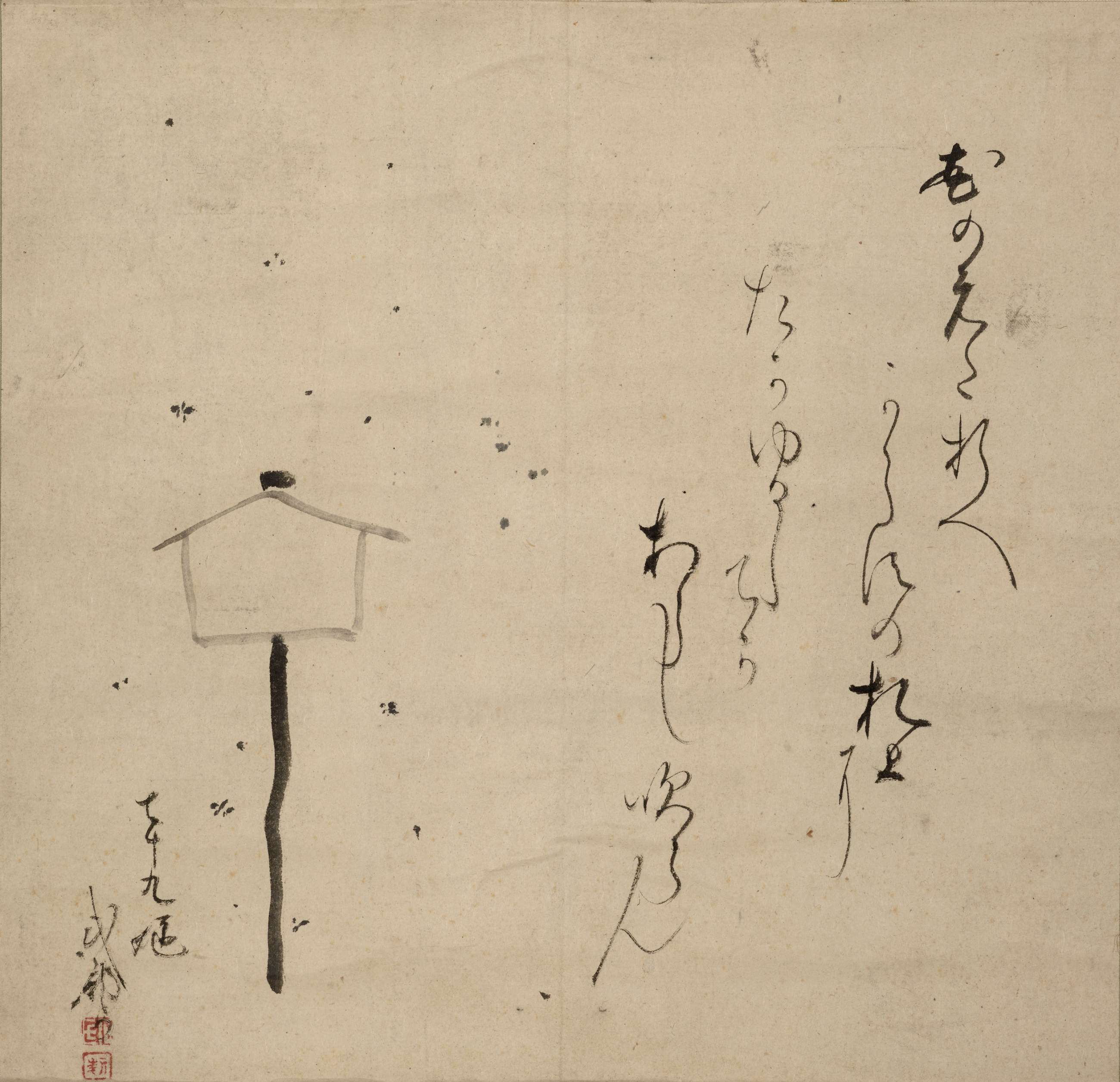

In Takabatake Shikibu’s time, signboards such as this commonly posted governmental edicts. In a veiled critique of unjust rules and restrictions, Shikibu asserts that nature and reason will ultimately prevail.

Flowering branches

must not be broken off.

So says the signboard.

But with whose permission

does the storm blow over it?

Being a nun, Ōtagaki Rengetsu could travel freely despite state-imposed restrictions on unaccompanied women travelers. Still, innkeepers commonly refused nuns lodging. The poem reflects her endurance as she found (and created) beauty despite the inn turning her away and having to spend the night unsheltered:

The inn refuses me,

but their slight is a kindness.

I make my bed instead

below the cherry blossoms

with the hazy moon above.