Literati Circles

United by a shared appreciation for China’s artistic traditions, intellectuals and art enthusiasts formed literati societies (bunjin). For them, art was a form of social interaction. In their gatherings, they composed poetry, painted together, and inscribed calligraphy for one another.

Literati painting (bunjinga 文人画) prioritized self-expression over technical skill. Following this understanding of the brushstroke as an expression of one’s true self, these artists constructed—and conveyed—their identity and personhood through art.

As in other realms explored in this exhibition, literati circles included women from different social backgrounds. But perhaps more so than any other social context, literati circles were accepting of women participants. Many prominent women artists in Edo and Meiji Japan flourished within these intellectual cliques.

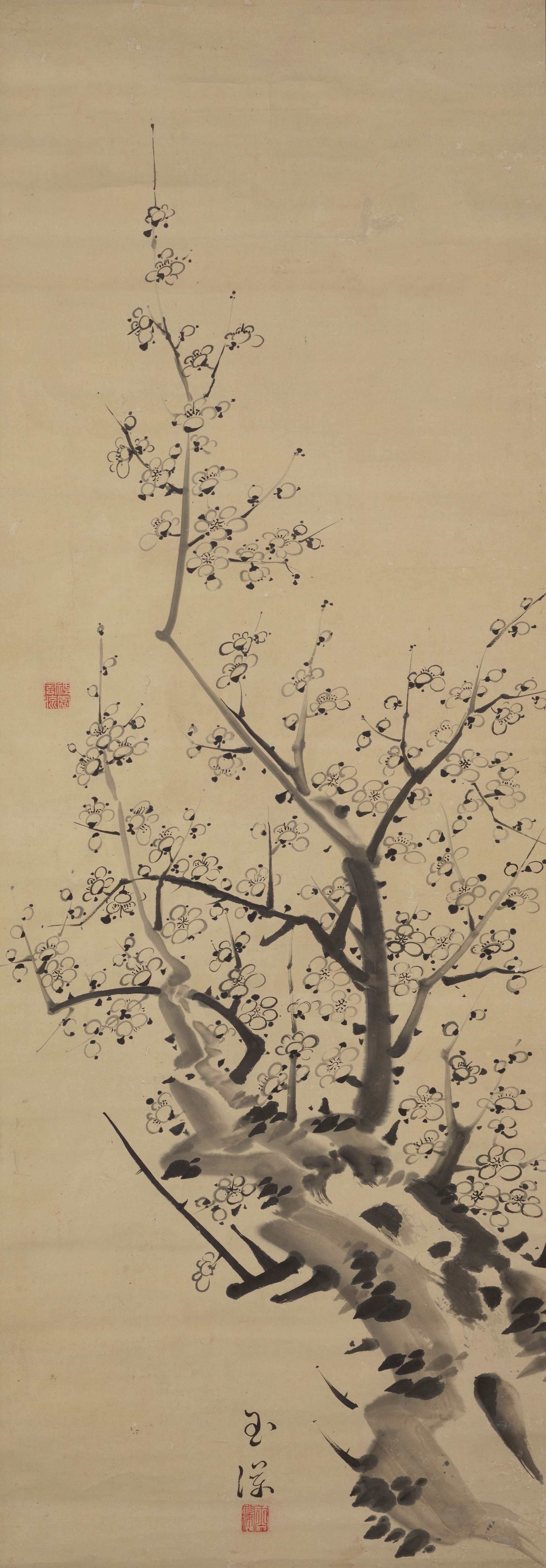

Tokuyama (Ike) Gyokuran is one of the Three Women of Gion, and perhaps the most famous of them all. This knotted plum, together with bamboo, chrysanthemum, and orchid, make up the Four Gentlemen (shikunshi), all common subjects for literati paintings.

Gyokuran and her husband, the accomplished artist Ike Taiga, were on such equal footing that they would wear one another’s clothes, paint together, and neglect their housekeeping chores.

This collaborative work (gassaku) was signed by different literati artists during an artistic gathering. Three of them—Atomi Gyokushi (1859–1943), Noguchi Shōhin (1847–1917), and Nakabayashi Seishuku (1829–1912)—are women.

Turtles, and especially the long-tailed minogame, are symbols of longevity. As the sun rises on the New Year, these perky turtles come to celebrate and commemorate the occasion.

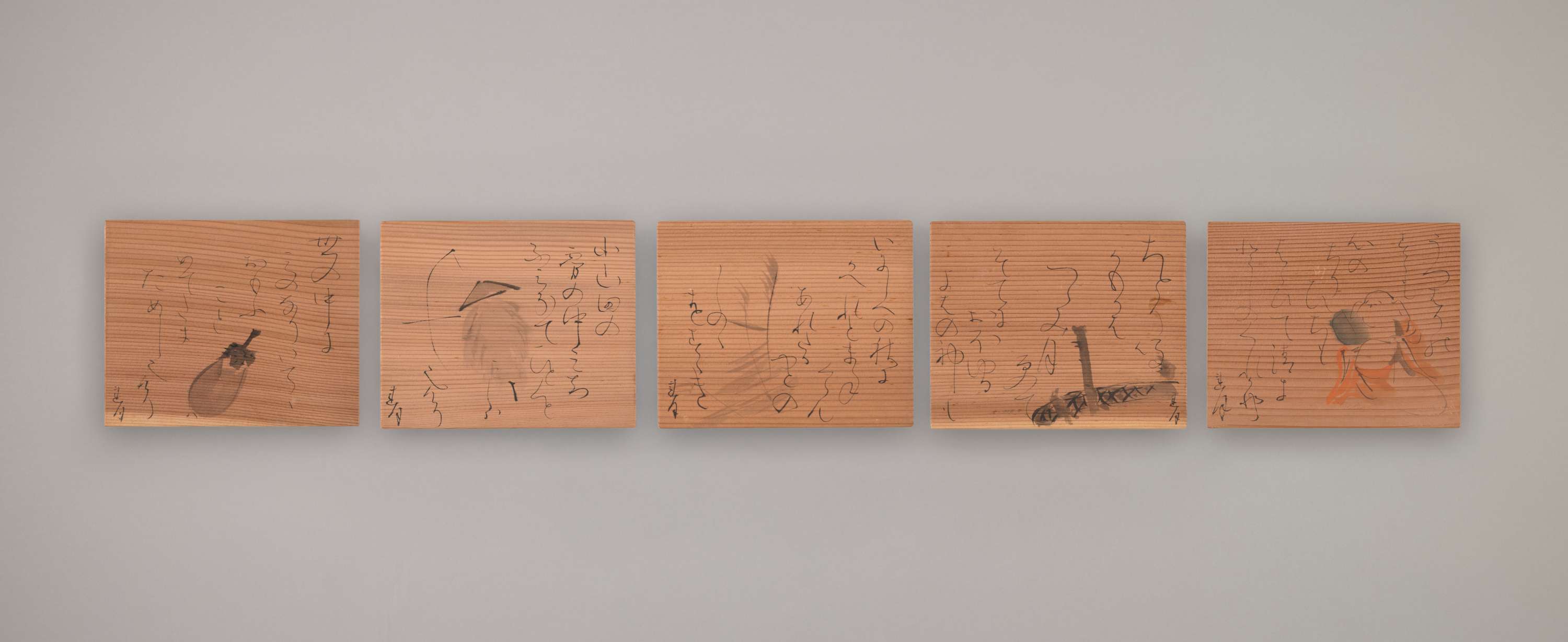

These small plates, painted for a literati gathering, were used for sweets to complement the sencha (green leaf tea) ceremony. These abbreviated paintings and poems burst with humor and personality. Their creator, the nun-artist Ōtagaki Rengetsu, was a central figure in Edo literati circles. She also produced other tea ceremony paraphernalia, as exhibited here.

This group of plates is also rare for its impeccable documentation. Their original box bears an inscription of authenticity by Priest Kōen of the Jinkō-in temple, where Rengetsu once lived.

The Three Friends of Winter, namely pine, plum, and bamboo, are a common subject of literati painting (bunjinga). But here, Ema Saikō creates an unconventional composition. From the crevice of a garden rock, wildly twisting pines intertwine and loop around bamboo and frenzied plum blossoms that jut out in all directions. Immortality mushrooms (reishi), sprouting in the foreground, allude to the subject of resilience in old age. Saikō painted this only four years before her death.

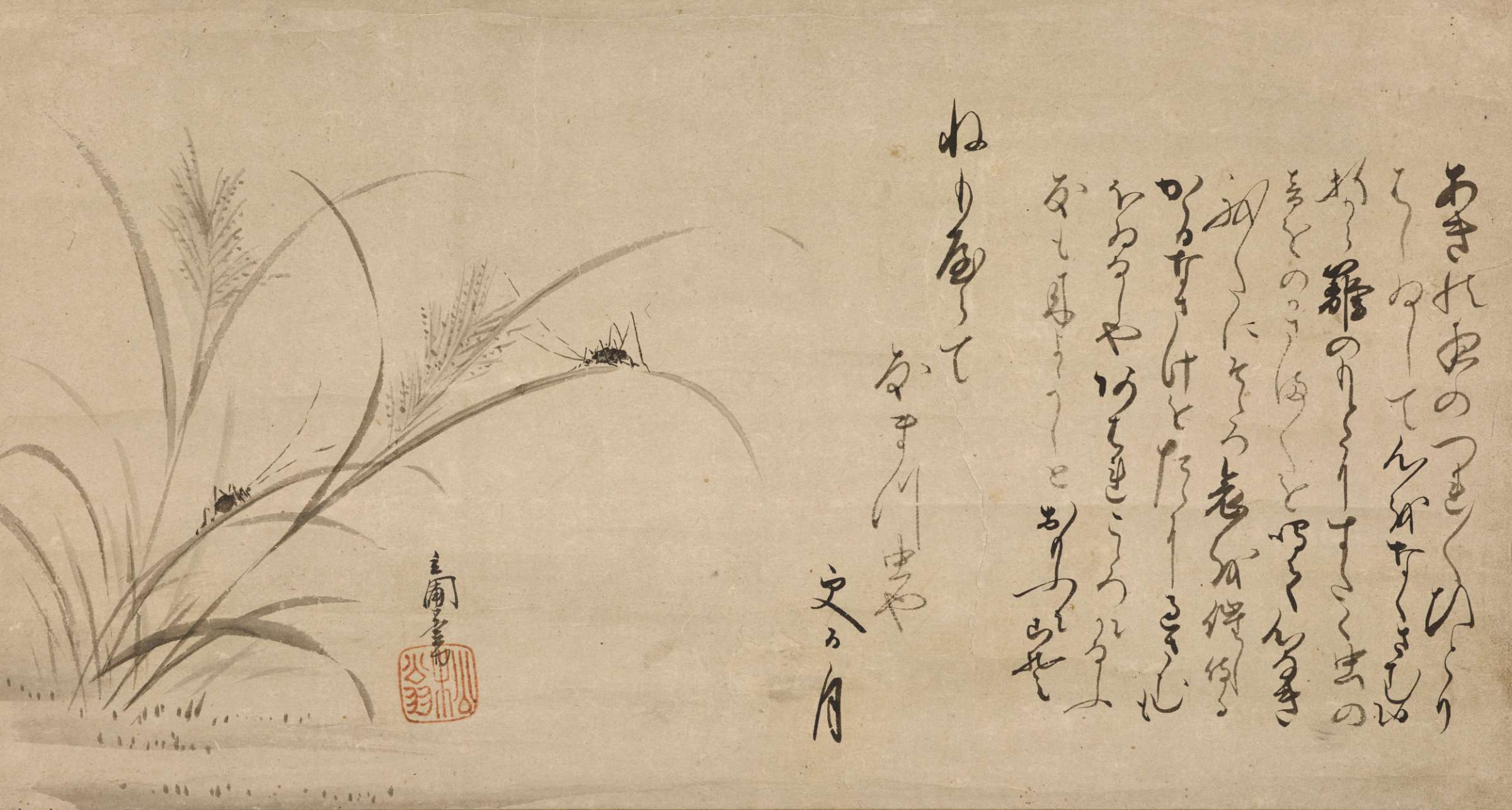

These paintings belong to the genre of haiga, an abbreviated and swiftly executed painting accompanied by an equally brief form of poetry called haikai, or haiku.

Nonoguchi Ryūho was one of the progenitors of the haiga form. Takabatake Shikibu, a poet-painter who exhibited talent at an exceedingly young age, continued producing art well into her nineties. In haiga, text becomes an aesthetic element, offsetting, complementing, and balancing the image.

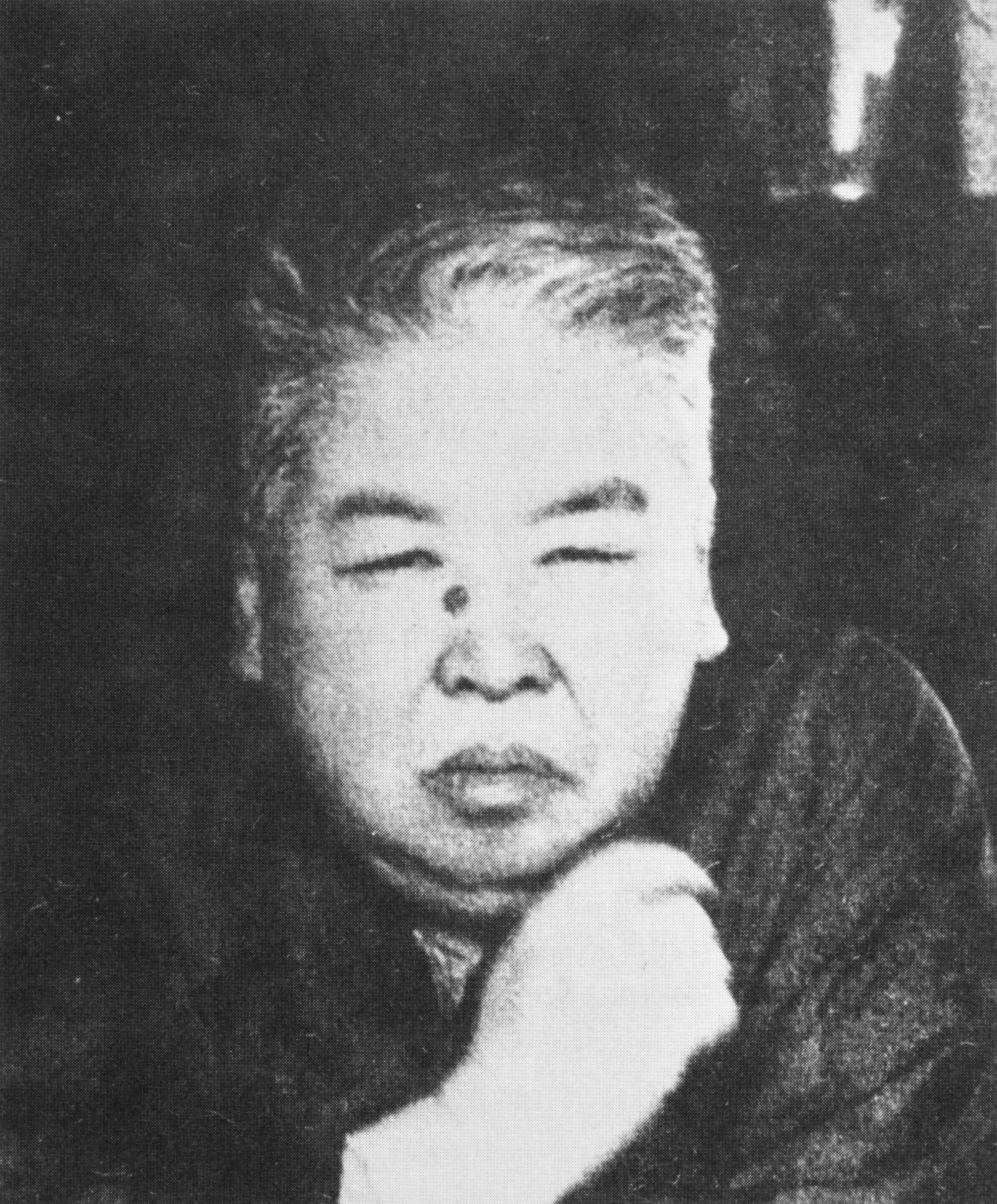

Okuhara Seiko 奥原晴湖 (1837–1913)

The tip of her brush

can wipe away

one thousand armies.

—Writer for Postal News, 1875

Okuhara Seiko (born Ikeda Setsu) was born into a high-ranking samurai family from Koga. Arriving in Edo (Tokyo), Seiko almost instantaneously garnered a large following and established a studio, which became a vibrant hub for literati painters, poets, and calligraphers.

Despite an 1872 prohibition of women cropping their hair, Seiko did just that (habitually carrying a “doctor’s note” citing a “medical condition”) and wore male attire. In art as in life, Seiko found a unique artistic identity with bold individual brushwork, which caused a sensation in Edo’s literati circles and beyond.

One of the period’s most influential literati artists, Seiko founded a school and had hundreds of followers belonging to all walks of life—from government officials and geisha to roaming samurai.

Noguchi Shōhin 野口小蘋 (1847–1917)

Good wife, wise mother.

—Popular aphorism in Meiji-era Japan

Noguchi Shōhin burst onto the literati art scene right at the tail end of Okuhara Seiko’s heyday. She exhibited remarkable talent from an early age and later enjoyed imperial patronage, becoming the first woman artist to be appointed Official Artist of the Imperial Household in 1904.

Shōhin cultivated a public persona as a paragon of womanhood, complying with the “good wife, wise mother” paradigm (ryōsai kenbo), which gained traction at the turn of the century. Like Seiko, Shōhin used the expressive qualities of literati painting as a vehicle of self-expression and identity-construction. But unlike Seiko’s maverick and masculine comportment, Shōhin’s persona leveraged her femininity.

Together, Shōhin and Seiko represent two wildly different visions of what it meant to be a literati artist.