Inner Chambers

The Inner Chambers (ōoku 大奥) are the secluded areas where women primarily resided within the courts and castles of the upper class. The term became synonymous with women and reveals the gender segregation of early modern Japan’s elite.

Daughters born into elite and wealthy households studied the fundamentals of the Three Perfections (painting, poetry, and calligraphy). They were not expected to become artists. Their artistic education was intended to prepare them to be proper companions for their male counterparts.

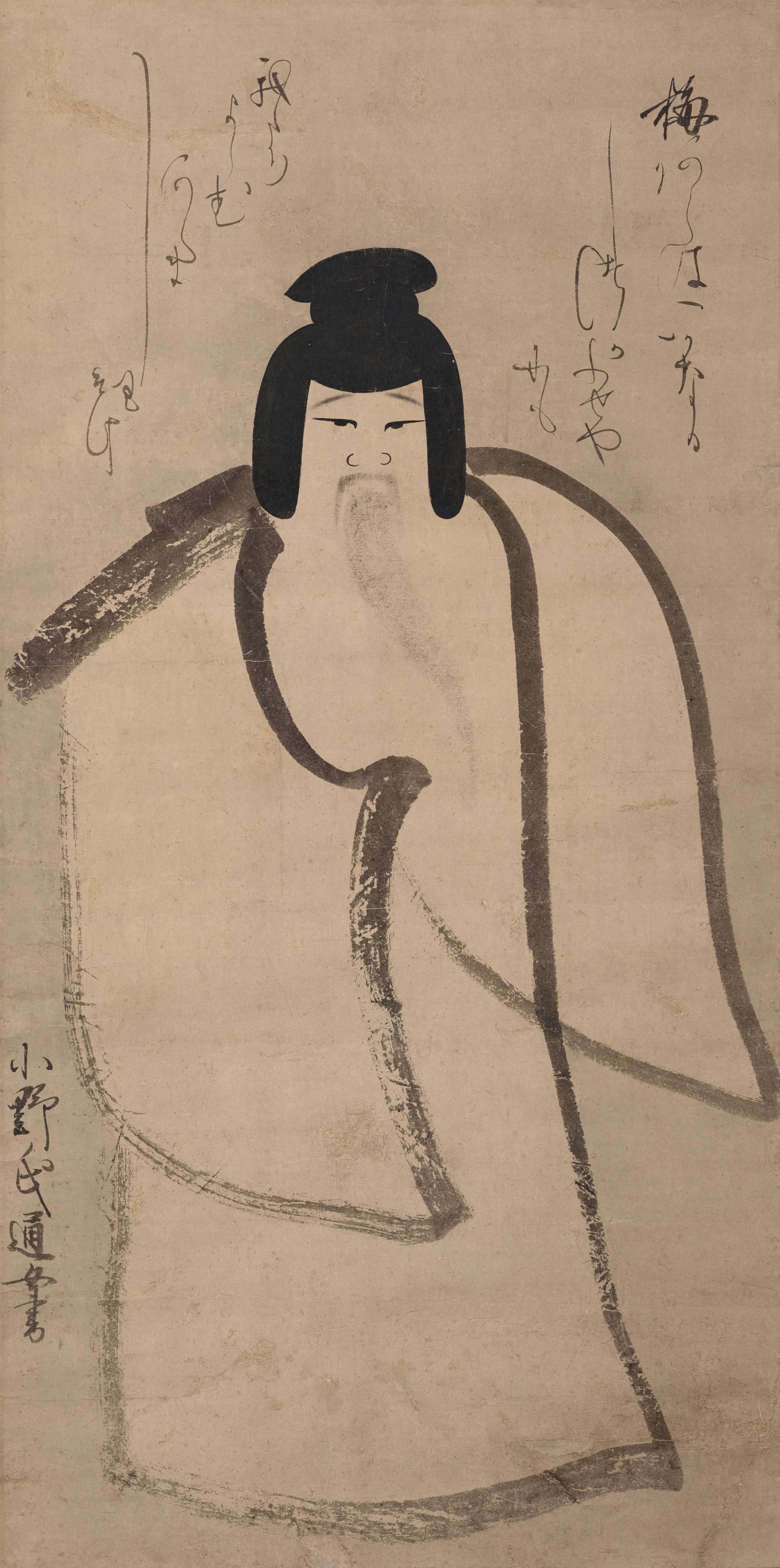

Yet sometimes exceptionally talented and driven women continued to cultivate these skills, paving their own paths as independent artists. Some, like Ono no Ozū, even served as teachers in the Inner Chambers, transmitting their knowledge in the arts to future generations.

ONO NO OZŪ 小野お通 (1559/68–before 1650)

Not much is known for certain about Ono no Ozū, not even her name (possibly pronounced Otsū). Apparently born to an aristocratic family and orphaned as a child, she was raised in Kyoto where she exhibited extraordinary talent in poetry, painting, calligraphy, and music. Ozū served as a lady-in-waiting, tutoring women in the Inner Chambers both for shoguns and for the imperial house. She likely served all three of the warlords known as Japan’s Great Unifiers (Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu). Generations of noblewomen emulated Ozū’s graceful style of calligraphy. She is known today as one of the greatest women calligraphers of premodern Japan.

Oda Shitsushitsu was a descendent of the famous feudal lord Oda Nobunaga, first of Japan’s Three Great Unifiers. This pedigree gave her access to a fine education. She studied under Mikuma Rokō (died about 1801), herself an important artist of the Mikuma school, which exclusively painted cherry blossoms (sakura).

The dabs of malachite—a costly mineral green pigment—painted in a technique of blending colors (tarashikomi) recall the decorative Rinpa school, which catered to the wealthy merchant class and aristocracy.

The painting depicts a scene from the Tale of Genji, the world’s earliest novel, written in the early 1000s by court lady Murasaki Shikibu. Here, Prince Genji peeks into the Inner Chambers and spies the young Murasaki, who will eventually be his greatest love. This anonymous early painting bears a forged signature of the professional painter Kiyohara Yukinobu, whose work is also included in the exhibition—a testament to her popularity.