Floating Worlds

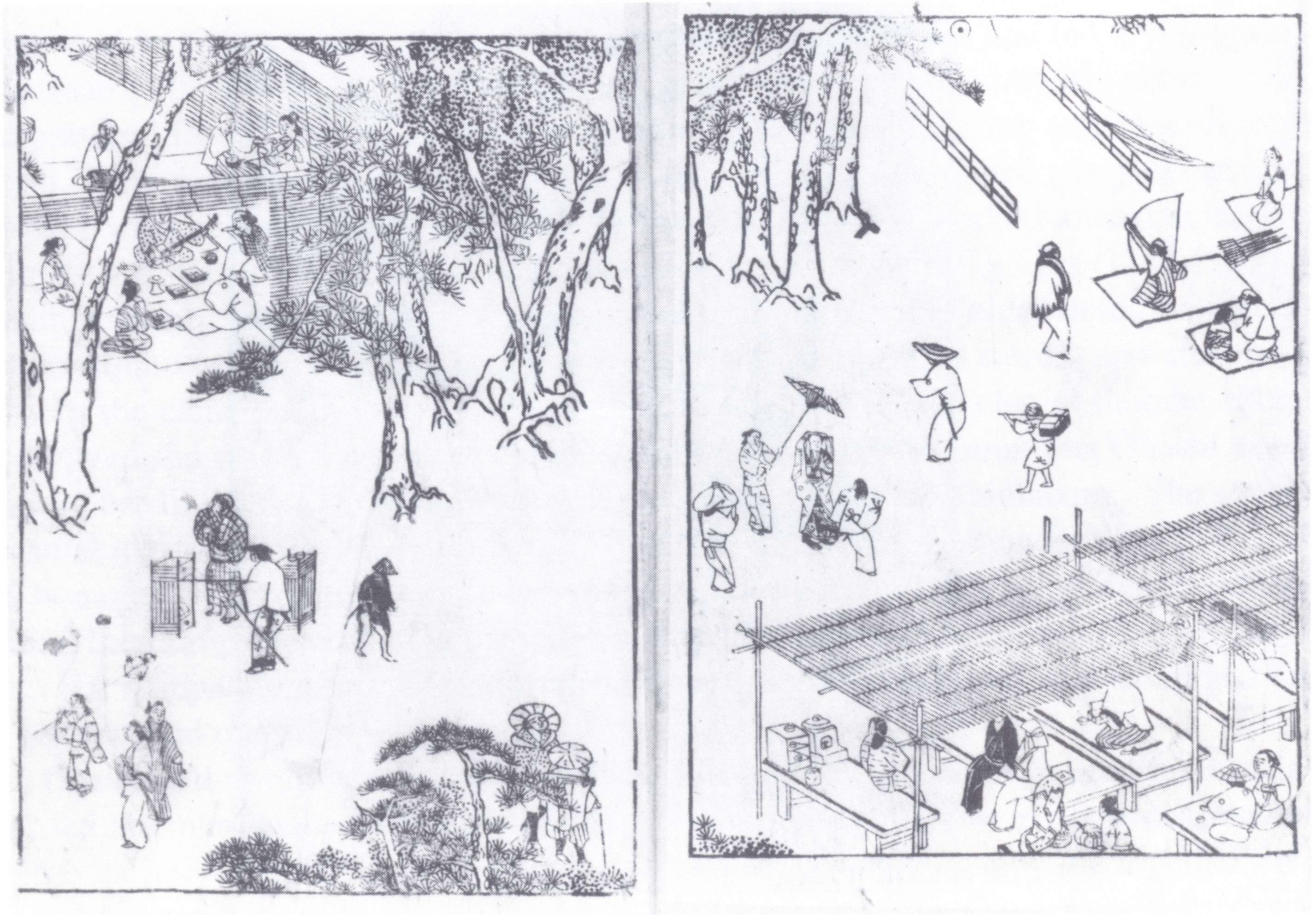

Starting in the Tokugawa period (or Edo period, 1615–1868), the Floating World (ukiyo) referred to the state-sanctioned pleasure quarters, or urban entertainment districts, which catered to male patrons who frequented the teahouses, brothels, and theaters. The term alludes to the hedonistic and ephemeral nature of this realm.

As was the case when becoming a nun, entering this sphere—whether as a musical performer (geisha), an actor, or a sex worker—meant leaving behind one’s name and constructing a new persona. Entertainers often cycled through several stage names, inventing and reinventing themselves time and again.

Being well-versed in the Three Perfections (painting, poetry, and calligraphy) was a coveted trait in women of the Floating World, adding to their allure. Some, however, transcended the strict confines of the pleasure quarters (sometimes even undoing their indentured servitude), becoming important artists and leaving their lasting mark.

Eternal art in a floating world.

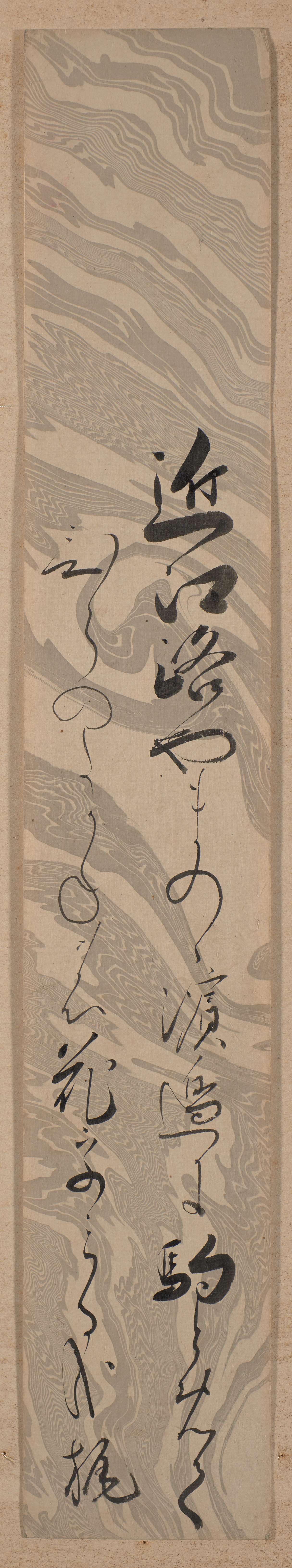

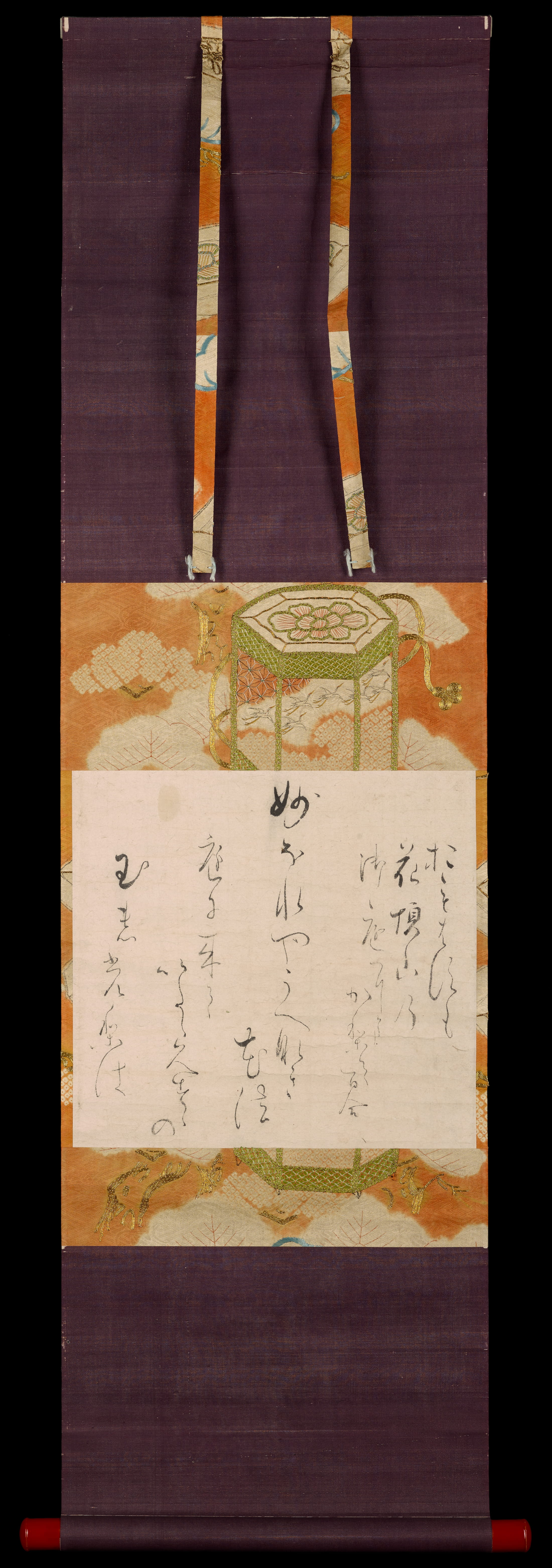

These poetry slips (tanzaku) were written by women and men occupying different social realms, including pleasure quarters, aristocracy, and monastic orders. Written in private or in gatherings, tanzaku were saved, exchanged, and sometimes discarded. These floating tanzaku therefore existed in a space between art and ephemera.

This display is a reinterpretation of the traditional mounting in a scattered arrangement (chirashigaki). A modern example bears the poetry of Takabatake Shikibu, a literati artist whose works appear in the next section.

Ōhashi is the stage name of Ritsu, born to a wealthy samurai family and trained in various arts as a child. When her family lost their fortune, they sold her to a brothel. With her talent and dazzling looks, she quickly rose to the highest rank of tayū (Grand Courtesan) in Kyoto’s Shimabara pleasure quarter. Although highly admired, she remained beholden to her clients and patrons.

Her poems here read:

Last night’s affair,

this morning’s parting. Which will be

the seed of love?

So you say, though . . .

The dawn has come.

My hands wring out my sleeves, making the pools

overflow with my tears.

Three Women of Gion 祇園三女 (1600s–1700s)

“The Star Festival—

Off to hear good poetry

at lady Kaji’s teahouse.” —Takarai Kikaku

「七夕や

良き歌聞きに

梶が茶屋」

宝井其角

Kaji, Yuri, and Machi were owners of a famous teahouse in Gion called Matsuya where many of Kyoto’s lovers of art and poetry would meet. Together, these three remarkable women formed a matriarchal artistic lineage.

Kaji of Gion was a gifted poet-calligrapher and the first owner of the Matsuya teahouse. She later adopted Yuri and trained her in poetry as well.

Yuri of Gion established herself as a renowned calligrapher and painter in her own right.

Machi of Gion, Yuri’s daughter, is best known by her later name, Tokuyama (Ike) Gyokuran, and was a formidable literati painter, calligrapher, and poet. Her work is included in the following section, dedicated to literati circles.